Our Innovation Lab’s featured wrist brace has found a new friend!

Matt Skolnick, 26, a graduate student studying social work at Stony Brook University, has a genetic bone condition, type I Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI) that affects about 6 to 7 per 100,000 people worldwide. The term “Osteogenesis Imperfecta” translate to, and literally means “imperfect bone formation”. People with OI have bones that are sensitive to breaks and fractures from what would be considered mild trauma, like bumping an arm or leg, or a trip or fall.. According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, there are currently eight recognized types, varying in characteristics and severity.

The milder and more common one is Type I, which is what Skolnick experiences. Bones are most fragile and easily broken during the younger years, childhood, and into adolescence. He compares it to “Osteoporosis in reverse”. After puberty and into adulthood, the bones get stronger, and breaks and fractures begin to occur less frequently. People with OI can experience up to 100 or even more fractures in their lifetime, depending on the type of OI they have. Skolnick said that he has experienced a total of 25 fractures, type III, some of which required surgeries to repair. Type III fractures are also known as Salter-Harris fractures, where they occur through a growth plate, typically unique to younger children. They have a more favorable prognosis, and rarely result in any functional limitations. He shares that the most common places for breaks are in his arms and legs – particularly his left leg, which he has broken four times. He chooses to use a wheelchair because he believes it is the safer option, and has helped to prevent more severe injuries like broken arms and legs from falling.

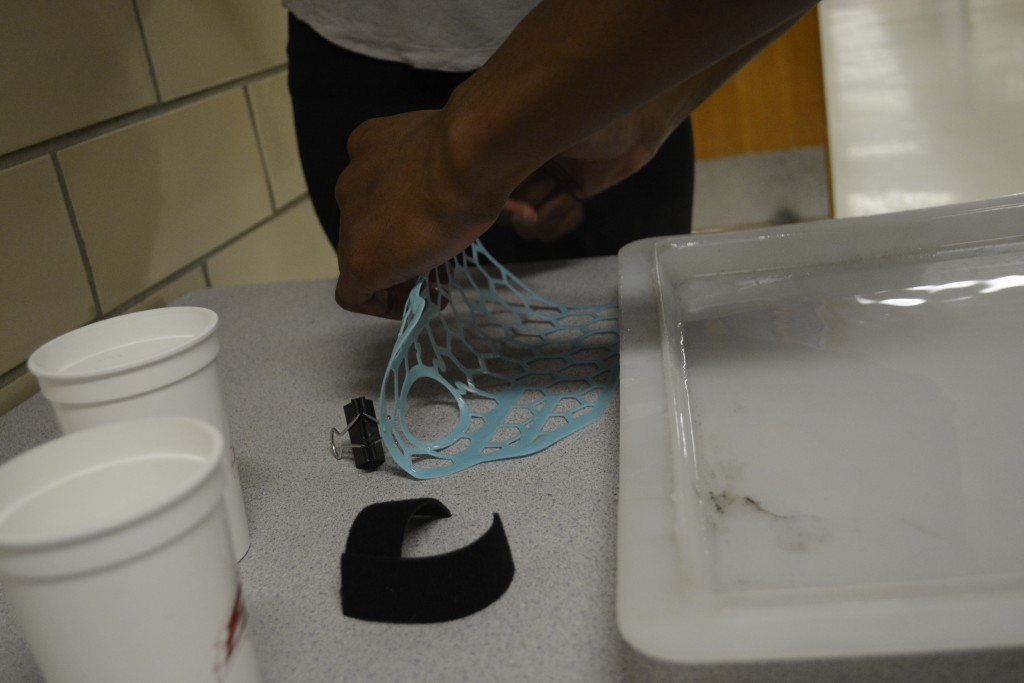

Skolnick first came across our Innovation Lab’s wrist brace at our HSC Pop-up table earlier this semester. He has seen other designs about different 3D printed casts as the future of healing bones. They provide the lightweight breath-ability and custom fit that current casts lack. Casts that are currently used have been the same for many years. They are stiff and made of plaster and/or fiber glass to immobilize the joint or bone after a fracture. These casts cannot get wet and need to be covered with plastic bags when showering. They are also known to get itchy and uncomfortable, and are removed by saw. While this is known to be a safe procedure, it may be a traumatizing experience for young children. These new designs are significantly less bulky, waterproof, more comfortable due to the fit, and even stylish in some peoples’ eyes. They cost less, and can be produced in a much faster rate – some taking only 20 minutes. Skolnick was excited to see that Innovation Lab on campus has it available, in our own version of it. He came by our lab to see it again in person, ask us questions, and to get his own wrist brace.

Skolnick has plans to work in higher education, preferably in academic advising or career counseling. He became interested in it through helping his older sister with course selection when she was a returning student at Suffolk Community College. He enjoyed guiding her through the process of figuring out what she wanted to do, and what she could do to achieve those goals. Skolnick looks forward to graduating with his Master’s degree in December and obtaining a job where he can help other students.

“The most disabling aspect of a disability is the environment. Whether it be ramps, peoples’ attitudes, or just plain lack of expectations,” Skolnick explains, “Overall, one thing I think it teaches us is how to adapt and think outside the box, working around it to just do anything anyone else could do. This is especially true for someone who has experienced it since birth. It is something I have always known and experienced. This is our idea of normal, and I am proud of how I am.”