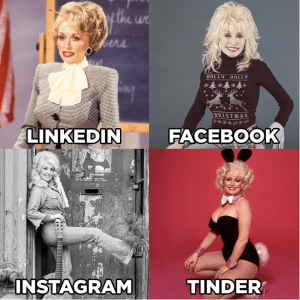

In a secondary ELA classroom, emphasis on student development falls within reading, writing, and speaking standards. Each of these categories of standards lies within the purview of social media. For example, students read and interpret posts written by other users inside and outside their social contexts, memes, and videos; they write their own tweets and compose their own images; in addition, students speak through the very creation and maintenance of their profiles. Instead of learning from teachers and books how to approach situations and circumstances, students today are learning from social and digital media. “As teenagers learned to navigate social network sites, they developed potent strategies for managing the complexities of and social awkwardness incurred by these sites” (boyd 2). Digital natives teach themselves how to use and operate technologies, and they intrinsically base their  behaviors in networked publics off of others. Just as these maneuverings are learned in real-life contexts, now they can be learned online on social media platforms. It has become increasingly rare for students to write letters to their friends or even talk on the phone, but ranting through text or sending Snapchat videos lean toward a more instantly gratifying, active, and direct approach to reading, writing, and speaking than the “traditional” means of communication. “Social media has taken social situations out of traditional contexts,” which is why there is such a push amongst teacher preparation programs and school districts to forego “traditional” means of teaching for newer, digitized instruction (boyd 4).

behaviors in networked publics off of others. Just as these maneuverings are learned in real-life contexts, now they can be learned online on social media platforms. It has become increasingly rare for students to write letters to their friends or even talk on the phone, but ranting through text or sending Snapchat videos lean toward a more instantly gratifying, active, and direct approach to reading, writing, and speaking than the “traditional” means of communication. “Social media has taken social situations out of traditional contexts,” which is why there is such a push amongst teacher preparation programs and school districts to forego “traditional” means of teaching for newer, digitized instruction (boyd 4).

Once adolescents learn how to navigate networked publics within and outside their social groups, they are able to apply these skills and abilities of navigation to unmediated social situations and contexts outside of networked publics, “The publicly articulated nature of marking social relations can prompt new struggles over status and result in heightened social drama, but as teens learn to manage these processes, they develop strategies for maintaining face in a social situation driven by different rules” (3-4). The use of social media creates transferrable communicative and navigation skills among  adolescents, an effective tool aiding their engagement and acceleration in education. In addition, the “wide array” of social media usage contributes to “everyday teen practices” as well as the intrinsic motivation teens have to incorporate facets of themselves into the networked space (boyd 2).

adolescents, an effective tool aiding their engagement and acceleration in education. In addition, the “wide array” of social media usage contributes to “everyday teen practices” as well as the intrinsic motivation teens have to incorporate facets of themselves into the networked space (boyd 2).

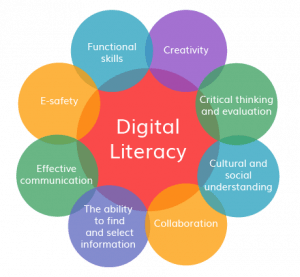

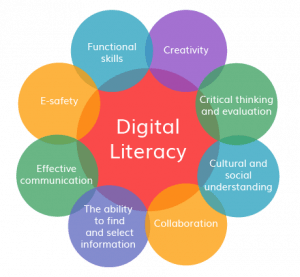

Teen practices and usages of social media are interconnected with their literacy learning. Literacy involves the wide array of definitions and schools of thought; it is not simply the process of being able to read and write. Instead, literacy extends beyond the limitations of dominant powers concurring what criteria being able to read and write aligns with. Literacy is a range of practices, experiences, and relationships. According to David Bloome, it:

recognizes that there are many ways of using written language and that these uses reflect various cultural ideologies about what written language should be used for, how it means, how people differentially engage in uses of written language in different contexts, and how people socially congregate during social events involving written language (Bloome).

Educators and teacher preparation programs are usually required by state certification standards to be well-versed in literacy education. Educators should have a fundamental understanding of the range of literacy practices students of all backgrounds bring to the classroom. Further, they should be able to  incorporate and build on those practices. As the digital archive, Stories that Speak to Us, indicates, digital narratives give students an opportunity to create their own literacy narratives. By diving into their own literacy experiences and telling their own story, they are able to take ownership of their stories, their practices, and themselves.

incorporate and build on those practices. As the digital archive, Stories that Speak to Us, indicates, digital narratives give students an opportunity to create their own literacy narratives. By diving into their own literacy experiences and telling their own story, they are able to take ownership of their stories, their practices, and themselves.

When students have the opportunity to write their own narratives and share their own stories, they can have their voices heard in a new and empowering way. Cynthia Selfe in an exhibit of the same archive writes, “In this sense, personal narratives are not only a vehicle for formulating identity, but also a way that individuals and groups tell themselves and their world ‘into being’” (Selfe). Just like social media, digital narratives allow students a platform to reflect on their own practices and experiences in an educational setting. They develop more than simple literacy skills, but feelings of empathy, empowerment, identity formation, and ownership of their experiences and storytelling. Just like literacy learning, educators should push to build on what practices students already have and bring to the table within the classroom: namely, what students like and are partaking in in their free time, and how to engage them in creating authentic writing through parallels with social media.

In contrast to these principles, many schools approach phones and technology through campaigns of warning. They want students to exercise caution while partaking in the underworld publics that are more “public” than they may seem. By warning students away from their social media identities and practices  telling students to put their phones away, traditional education systems dissuade them from engaging with the world at their fingertips. Or more accurately, dissuade students from engaging in a classroom so far removed from their digital literacy practices. However, teens “formally make their presence known through the explicit creation of profiles” and the use of social media (boyd 119). In forcing students to remove themselves from their connective online identities, schools miss an opportunity to engage students in their natural, organically produced literacy practices. While the safety issues surrounding social media are certainly prevalent, it may not be a school’s responsibility to teach

telling students to put their phones away, traditional education systems dissuade them from engaging with the world at their fingertips. Or more accurately, dissuade students from engaging in a classroom so far removed from their digital literacy practices. However, teens “formally make their presence known through the explicit creation of profiles” and the use of social media (boyd 119). In forcing students to remove themselves from their connective online identities, schools miss an opportunity to engage students in their natural, organically produced literacy practices. While the safety issues surrounding social media are certainly prevalent, it may not be a school’s responsibility to teach  students how to use social media or Microsoft Office outside a technology classroom. Rather, schools should be making use of these technologies that students are already engaging with to enhance learning in the classroom. By shifting gears from the cautionary tales of navigating social media (which are certainly important and meant to be shared with students!) to the positive ideologies of digital media in education, educators are making learning more relevant for students and giving them opportunities to develop ownership of their own work and transferrable skills applicable to their everyday practices.

students how to use social media or Microsoft Office outside a technology classroom. Rather, schools should be making use of these technologies that students are already engaging with to enhance learning in the classroom. By shifting gears from the cautionary tales of navigating social media (which are certainly important and meant to be shared with students!) to the positive ideologies of digital media in education, educators are making learning more relevant for students and giving them opportunities to develop ownership of their own work and transferrable skills applicable to their everyday practices.

Back to Final Project Homepage