Disability and the Construction of Virtual Identities: James Au and “The Nine Souls of Wilde Cunningham”

In his 2004 article “The Nine Souls of Wilde Cunningham,” James Au discusses the way in which a group of severely physically and mentally disabled users of the game Second Life achieve the means to live an abled existence virtually. The game, originally created by Linden Lab and launched in June of 2003, enables users to create digital avatars in order to interact with other avatars, places and objects; through the use of the mainframe “grid,” users are able to communicate with other users, engage in group and individual activities to build and trade items, and even convert real money to “Linden Dollars.”

The ability to create and manipulate avatars within Second Life allows the members of Wilde Cunningham to “see what the [outside] world is like from a first person perspective,” something Au emphasizes would be denied to them otherwise. The notion of Second Life users being called “residents” within the game itself was something that really stuck out to me. Since Wilde Cunningham is comprised of members of a care center, the “resident” term takes on a certain duality. “Resident” within the care center connotes a relatively fixed condition of disability; “Resident” within Second Life, by contrast, connotes [virtually] limitless possibility- for dress, speech, and movement. Another interesting consideration is Lilone “acting as the interface” between the members of Wilde Cunningham and the Second Life platform; many of the members are limited to the point that they cannot manipulate the website themselves- due to the loss of a limb, an inability to read, etc.- and so Lilone navigates the tools for them: one user for nine (ten if you count Lilone) different user perspectives. While this would seem to pose a question of agency, the group describes the experience of Second life as “empowering and freeing” (Danny), the use of pictures as “pieces of their bodies” (Scott), and that it gives them an opportunity to defy the expectations that people with disabilities such as cerebral palsy “are not intelligent” and “lack humor” (John).Why? Because it allows them to communicate- textually and visually- with an ease that was unimaginable before the birth of the cyberworld and to reclaim the “loss of dignity” their mental and physical handicap presents. Peppering his article with different images, Au chooses mostly avatars and screenshots from Wilde Cunningham within the Second Life portal, and only at the very end of the article does he insert three real-life photographs of the group members. In these photographs, none of the members of the group face the camera directly- their backs are to Au’s camera and, by extension, his audience and their faces are transfixed on the screen- demonstrating a clear preference to be represented virtually rather than realistically.

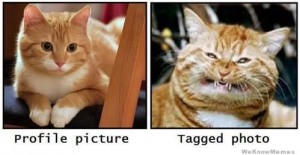

At the time that Au was writing, Second Life was a relatively new virtual platform, which naturally raises the question: How does this article relate to the ways in which people construct virtual identities online today? In fact, does it at all? I’m particularly drawn to the section of Au’s post which discusses the nature of online relationships and the [lack of] potential for the members of Wilde Cunningham, such as Micah, to engage with other users in this manner. Lilone cites the risk of harmful emotional side effects as well as limitations within the policies of internet use mandated by the care center as the reasons for discouraging such behavior. However, she also notes that “[to be] blunt, if you refer to Micah as being ‘special needs’ most women won’t look at such a man.” Implied in her statement, however, is the ability for the Internet, through the medium of the virtual avatar, to conceal different physical and mental imperfections. Much like Micah can hide behind the façade of Wilde Cunningham to confidently converse and flirt with users like Angelique in a manner he would never employ in “the real world,” people today utilize similar techniques through apps like Tinder, Hinge, and Bumble. Carefully chosen “profile pictures,” oftentimes heavily edited, coupled with a once sentence “biography” entice other users to “swipe right” and chat within the app itself; however, these carefully crafted personas often do not meet expectations when individuals meet one another in the real world.

As a result, many individuals create profiles within these apps for the sole purpose of conversing freely with potential “matches,” and have no intention whatsoever of ever meeting those they talk to. The apps provide a much needed outlet, just as Second Life does for the members of Wilde Cunningham, to express themselves relatively anonymously with real people who “exist,” to them at least, far away in the cyber realm.

Sources:

Au, James. “The Nine Souls of Wilde Cunningham.” New World Notes. Website. 15 Dec. 2004. Web. 8 Feb 2016.