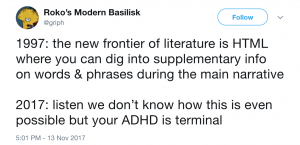

Initially I had been excited to write about hypertextuality and the flow of information across digital windows, suites of programs, and pages on the internet, I even uploaded a screenshot of one of my favorite jokes from twitter to include:

But, appropriately enough, I got distracted from that line of thought by a number of points Douglas Eyman makes in his “Theory” section of Digital Rhetoric that resonate with some recent experiences I’ve been having on the internet. Of particular note, are Eyman’s “ecologies of use”, his invocation of Alexander Galloway’s Protocol, and the instability of digital works as they relate to blogging and social networks before Facebook dominated the market.

The impetus for my renewed interest in this world goes back about two weeks to the anniversary of Mark Fisher’s death. Fisher was an author, academic, music critic, and perhaps most famously (or at least most importantly for the purposes of this post) a fairly prolific blogger, living and working in England until he took his own life early last year. Simon Reynolds described Fisher’s “k-punk” blog as a one-man magazine superior to most magazines in Britain. The elegance and reach of Fisher’s writing, the evangelical urgency and caustic critique that seared through his rapid-fire communiques, demanded a response. And just as fellow bloggers picked up his baton, Fisher was always building on other writers’ arguments, pushing things further than you’d thought possible.

And on this first anniversary a number of his old friends, colleagues, and students have been posting their own blogs about Fisher and about his ideas, and about blogging as a medium. Reza Negarestani’s inaugural “Toy Philosphy” blogpost, like Reynolds’s description of k-punk, seems to take the ecosystem of circulation and use to its most utopian conclusion:

For this reason, I am not convinced about keeping the components of an ongoing research secret. If people can build on your ideas even when your ideas are still in their larval stage, then it does not matter whether they reference you or not. As long as ideas and concepts can be enhanced, refined and propagated, plagiarism is a virtue rather than a vice. The task of a philosopher is to highlight the hard fact that the concept is that over which no single human has a final grip. Therefore, the whole obsession with working in secret, keeping things in the closet until the book is published is absurd. To take the concept of open-source seriously, one must first take the idea of an open-source self seriously.”

In this formulation the web becomes the tool through which ideas break free from the constraints of intellectual property, publishing companies, and even their individuated human hosts. If the MA thesis Eyman describes in his book increases its use-value by being extended beyond the physical library onto the internet, what can be gained if the ideas/notes/drafts that went into the final product held by the library (not to mention the final paper itself) were made freely and widely available on an open blog? This form of writing prides itself on its lack of authority and finality, as Eyman explains it is “easily manipulated and remixed” through commenting, quoting, reposting, opening itself up to interpretation and quick response.

Unfortunately, the ease of manipulation goes beyond the level of ideas, to the material realities of the internet which can just as quickly begin to impose itself on users. I’ve personally found in researching some of Mark Fisher’s earlier writing, either before or concurrent with the beginning of his k-punk blog, that much of the internet he published on doesn’t really exist anymore. In some cases you can get lucky using archive.org to recover bits and pieces of old pages, like this page which is actually Fisher’s grad school thesis, Flatline Constructs: Gothic Materialism and Cybernetic Theory-fiction.

But in many cases intellectual property laws have forced the removal of images, texts, and, most famously, music from parts of the internet which can never be fully recovered, leaving sites shells of their former selves. In other cases, sites can no longer afford to maintain the physical servers which host their content, or are bought by entities with no interest in keeping up outdated content. If Negarestani and Fisher’s blogging embraces the most utopian aspects of digital networks at their best, it is Alexander Galloway and Eugene Thacker that remind us of their constraints, that these sites are owned and controlled largely by profit, even if they don’t impose the same paywalls as university databases or mine your data Facebook:

networks, by their mere existence, are not liberating; they exercise novel forms of control that operate at a level that is anonymous and non-human, which is to say material”

The lack of control users have over the past and future of the internet seems to be a foundational problem at the heart of digital rhetoric, and while projects like Rhizome’s Webrecorder offer some solutions going forward, though there are no real guarantees that the databases they compile will remain more stable and free than independent websites and pre-social networks of the 1990s.

I want to end this post by asking if there are any better solutions that already exist, and if not why not? Is there a proper balance between the stability of printed books housed in universities and the potential openness and freedom of exchanged offered by web platforms that aren’t just Facebook and Google?

And are these limitations a case for maintaining old mediums even as they become increasingly unprofitable and obsolete?

“It’s a book. It’s a non-volatile storage medium.” – Blank Reg, Max Headroom (1987)