Here is one of many possible versions of my final video essay:

Hopefully the project doesn’t lose too much of its full effect in this more constrained form, but until I level up my Max coding skills and learn how to turn patches into standalone apps, this the only way I know how to share the final product. I don’t necessarily want to say too much about the video itself because (ideally) it should make sense on its own; although what and how much “sense” it actually makes is a matter of each viewers’ susceptibility to the intended Burroughs-esque brainwashing tactics borrowed from his audiotape cut-ups.

Based on some of the responses to my presentation, I do want to include a little more about the program I used to make the project, and use that as a way to hint towards some themes that I hope everyone was able to “unscramble” from the video. Aside from just being a fun program to make things in, I’ve found myself returning to Max as an object of study because it is such an unrestricted “ecology” of incomplete elements. In his “How I Learned to Love a Program That Does Nothing,” Max developer David Zicarelli explains that unlike a more maximal music composition software like Ableton Live or Logic which emphasize their built-in features and plug-ins, Max included as few parts as possible but those parts were meant to be endlessly connectable. The interconnectivity of various elements became central to my project, through the plug-ins offered natively in Max, patches made my other users that I found on the Max web-forums, and my own audio/video files made outside of Max, I was able to build an “eco-system” of an essay.

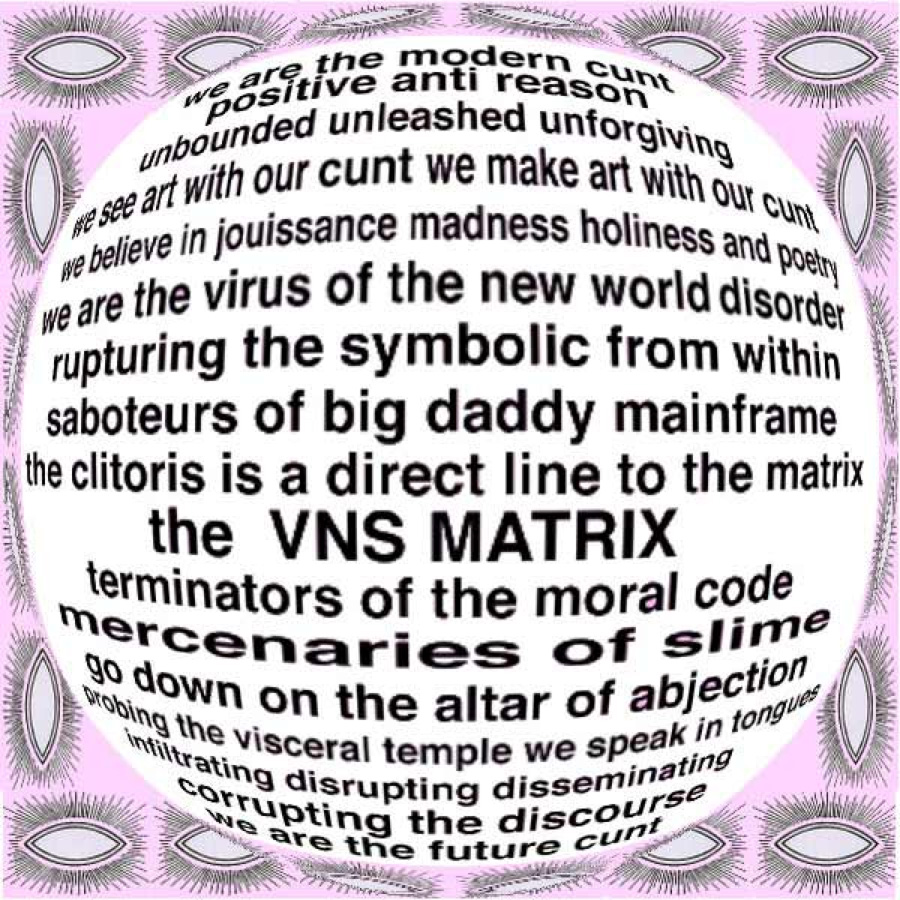

During the 1990s, in the early days of the internet on personal computers Sadie Plant applies a phrase from the French philosopher/psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray about women to the computer, saying they are capable of “Nothing. Everything.” This unity of seemingly opposing ideas comes from the French psychoanalytic tradition of approaching feminine subjects as un-unified sites for masculine subjects to mediate themselves through thanks to their intrinsically inter-connective nature and infinitely capacity for mimicry.

Plant saw the increasing presence of computers as a imminently liberating force for the subjugated feminine subjects, in describing the sort of thinking and acting they engender she says:

Every software development is a migration of control, away from man, in whom it has been exercised only as domination, and into the matrix… which has no place from historical man: he was merely its tool, and his agency was itself always a figment of its loop”

Like the hypertext literature coming out at the same time, Plant’s analysis was more optimistic than what has played out in reality as centralized social media corporations dominate much of the space on the internet. Unlike hypertext works, which seem to have become dated after only a few years of interest, Plant’s take of the situation remains possible. Her reading is by no means entirely optimistic; she is quick to concede that much in the history of computing comes from militaristic and corporate desire for increased domination, but it is through these systems of cybernetic control that patriarchal institutions become open to subversion, hacking, undermining, etc. because of the sort of open-ended, decentralized, “feminine” thinking they produce.

Zicarelli’s description becomes especially interesting to me as a part of the lineage of the idea of computers as “universal machines.” Like Plant’s computer, or Irigaray’s woman, Max’s schema of basic, but connectable objects lends itself to the production unconventional mechanisms and generative works. Where the hypertext offered readers a sense of agency as a part of the unfolding of the text, the cybernetic system Plant describes rejects centrality of the reader, the text, or the author in favor of a circuit on which the identities of all three run together and become indistinguishable from one another for the length of their connection. In Max this often takes the form of building patches that operate independently, in a sense playing themselves, or invite participation from audiences and environments. My project takes advantage of this in a fairly straightforward way which you can see the insides of here:

Step one of my process was to standardize the style of the videos I uploaded. As you can see in the above photo, I sorted the videos into 5 types: 89 videos with texts, 4 web diagrams (centralized, decentralized, distributed, and a neural net), 5 images from Shelly Jackson’s Patchwork Girl, 4 “pop-ups,” and one “BLANK” screen. All of these were set to the compatible color, contrast, and brightness so they wouldn’t conflict with each other when they were mixed together. Once organized in their respective playlists in Max, the videos were linked to controls operated by the music; turning on and off based on how many times the “Amen” drum break looped, with effects and positions on the screen being changed based on volume of certain frequencies as determined by the “Audiosplitter” object. Because the music was also constantly changing, thanks to the same controls based on its own sonic elements, the video elements became increasingly indeterminate for both the viewers and for me. Essentially, once I clicked the “X” in the top left corner, I gave up control of what was going to happen to the computer.

If you’re interested in downloading Max and running the patch that makes up my project this is its code you can paste right into an empty patcher (although it probably won’t actually work properly without the sound and video files that are local to my computer):

<pre><code>

———-begin_max5_patcher———-

5404.3oc6ct0baiikG+4jOEpT+35XSbiW1Z2G5s24gt1K0r6V69vLSWonknk

YBEoFRJamL0jO6K.uHQXSIBaBR6z4uqjTNjT5vyA.+vA.+I3e68ua40YODUr

bw+3h+7h28t+16e26pNj5.uq4++tkaCeXURXQ0ksbaTQQ3lnkWTetxnGJqNt

ykdh1CtKrb0swoa9Xdzpx5ubOWuKctXgvK3RW4O9dWrfwUGgRuzYwu07AKJ+

RRT0WW6WU59swoIQkUFmd7fY6KaOJo4nwqq9jYW+oO36294qutxurKp99X4x

E+l5L+82+d0+bwn8ZGxY7ZeB+IdsX57Z2YyqYAmwq4t9WJtXQfz4YxeHrosr

lOeds+Y7ZAgnJj8H9ymqSmMW20yPW22Sbo+L35NymqeNtF2yQ4iyjW6Mabsy

gxYzJnlu+AnFMP0feZb44CpQOaAsnpX0mW67NSWY77wyNWWWDpSUO1ARmrsX

dJ854Ck4IDm0u4U8PGD3cvuqKymD+lYaN10U9TTd6W6cg4ogaiZN2k+2Qqxx

We7rwQ2eWbQ70wIwkeo68X1M2TD0DSpJ1c538IYq9bz504gaJVkmkjntLmly

sJId0mKuMOa+la6d7nzvqSht8oef5Sb2SOw0a1lsNR6Hx6coq04H8TBxptcC

DtGy4xqp.jPb63CFTd47zxKxABbOQ0KkkDxan1qPVkKOr9thXgRRoaVWE9m9

oE+R3tx84QK9+90+ze5W+CK1lIKHKV7S+Tek5280Ky+8eoNmHNTdGvCpR+xi

Ka6R7qJ6ENmprmYbYu2SJ6OFaaK6moNgYxgTPU845wtzwi55PlzdgYhYBO+g

yNHxJLrSMX1iNodL0yxd7MIYRid1ddn0YTQckHK25gLJbeIc6RNXkbYM0xn7

OV2bqaEa8H.smp6zCodcSV91vpaS2SFTtPRrBS2X2pCqRhByOaLymeLlwbqZ

1y4Jj+j0kszlVtpQZz8xu3m37+CKHFWcQlsRqqOgMJHzfS55U8NYQueed5Bt

w9e2hde6Tz2WShyjtlx+GUafOEWd4tjvujDWTdV+lDbvucI7C85Qp4DAu.Ng

r26c2FEu41JaPUeO8EQX8Ui3z8LHcnOJwF4wOnBLp+tNdUYbVZXtLoi1aw0g

kgMQklvR88ygYkryITnn3jnCc+d0+aQTdwUq9TQzcQ4woW8ulsZ+1nzxhq94

0YWGc0eLOZabjLQo+Xd1UDYj4ppH5BwkxTlZtwa+V+bbZseUkMk5Hctfjrrc

cnmU2jYokRS8whxvxnVOn68ZUHY29x17Yjkcsdc6Y+XqqHCW6cXNxe7IzkZW

153sMe5KdzWPY71nOVDsp3PBaZmNbeYl7lKurOiqbncYxJsseXYtd5e50xbL

66StKqHVUJ1uQU2SMmQ63RKEkuquyntShpC8O9TJOPVCJdUembUVhraoCw1k

g4atd4S9lyi1k0FAz+72n5a7zmdeQz5hxis6zOadSYtL37n.vwZOG5R3hGWi

3iJJmL+8SEN5Tpoexh7UctitP8mmVqn96VqpE2wqppki9cST5l3zCwu6tQ+r

2kkzuKpGW5+tXeZ7eceuNnb.D2Wl0azQFy08vZP56Zgo0+xESDTfCn.fB.J.

nPWn.CPA.E.T.PgtPAJfB.J.n.fBcgBD.E.T.PguOgBMGr9H1ZsrHCKbHdyD

3pVmmobh6cX1VmA6KKksWOiCxHJGj44czAqUFE+4OA0F3fjS5fu7ojeSw8wR

G6byFOgW4TLe2KCj+3FnJSqNxynbj8rWutdBAtAyyxRUDkHc+EThIgEGmCgE

QvjstLt9muv+hIaQaodzJg+wqjZf3koMLqrbsGUn4juZsmnhwpr8pNjkPaJ2

vPVW5f2yVYzhdiM7dhMhgV1t1+9hWEyGqVmvzzLYRbM4znzry+ypvjnKVbed

3tKVbSVx5KVjkuPsTWsx3QsTXmPDOpSsUVfkj+mI+1gfadVYlxWNbY6heH46

LU9PdNp7wy+np7TORAsZtk1nxG1IU4ivXL5Y0eYOB.5XQyHz.zrU84G25NBW

1jW2g81rty+Q1cQKBSWDuUlm5hjnaJuJWsZ+Wse2UqytO8D0Z1I+l9AtBiOs

R1nceXNHACUWgaZcEgqIBmn2ZMUkKVrBS2x7ulks820BEk3PE0OdRGQ.j5mN

MhbnIhwVr57hKVqB8inXcXEFRbNJYJA08fHYekRYk6OaorN3vU0hMbgr9f7G

FYRGzJmNAiY8EKkRh6QoTxCXGB.SnTJor2DJoTqYg547Q9i6zJnZB4siPJ0p

42sfeBER4a.cTRbqlmFOuixojv8OnsbhSKebjpoT1aie0ncMTRkAeeInxhx6

vRefk9.K8AVOTs0C89r7OuINOAvA.G.b.vgV3vpa1rEHAfD.R.HgNHAnoRvD

.S3GQ4SMrHa39UyDkKy43VxxqiFar8lBfgyUkeP8tNDMv9OsuADyeZe+N6Y8

8e4e+m+O+2docqPP2JnaEzsxum6Vg3pVeGWA+0taE9DuIf8TEg7K4Qx50KtK

dcT1h+xR4cdXs5PJ9KpS2mx.tQsYVElD+0ej0PTUukKboG2bwnBqIeHN+Eqc

fiENiP.AunUOUTqq2taXQS4FQ0DrAzLntIZcQF60dOYh4+leKYxkV0DgF3dX

iIaJUPf67nffgVD8lpHZd8zs74Txq9xmG35TOlroXCHhZ9PRnNeeMlj6itt.

6zHXPIXPIX9u0XBXiFALAvD.SnKS.qIFXBfI.lPWl.zNCXBfI7C3BZL7j5y+

PbprHpYV82F+PT9IdxN4xS9i8SRd8aIjtq8CavmC3.y2mzewSjeUIyj9v.+K

YoxNbJW7G9uVDtecb1hxLCdBxqtzhcxJ.k+Hu9O0SyKu9EdVyhc7xdjf6Yap

3LOMbc1hJ5udS2xG6uDPM64KryMgvT0h9vnG2PODzIaBv8HSzF9RR7cQWtIL

N8a80H33Y6xN6AtPZ1qape4rPTSNNyspli+PuBh5a8gNzvIOVl11gVy8+flJ

5YeI3z7nh3MogIp.1weS82aRxBqVIgp0A3vsrLojh1agtOLch5WxNG2+aXZO

vrg2Es9igxplwWuuL53uU73Yd+tvj8QY2bHmz1LR6DVRxR2b1RDsqt3VYRR8

b48cssgEmdN2VYQk5bev6vaGgGc9vp5Ut8d13TYdmgI8j2YmKRl2Q4gFH722

M2gWTBCCttlLRUKTdsr5b8e816hHu16cQ4goqy1tPLbzpdYtc8Tu7Mlrk0TH

r+xbepEzkJSu1f2zTjlpIpmM1IbAcEy0q+Px.tMyeVca1L41hy60Nzm50SX0

745s9HUbNul55NqdMwxdciT2nCCu7pUvhqZqWKv.ot07JGj8bSXw4nCJGP5Y

TAUOIqvCLKM3KlrstRhe8lWnDAHZEyAq9HSvt.hvaB1EPNQ2bQq2D8MC7bhy

AOmWKikQ648zsuniZlRKKh+ZcxtrKcFJ49l.SmO8gT794bUhV1Kj8O8O+MYF

aCGyn9ziwrfmaLyb3QvyMl0jW+7DsVGkTFZPMLpfWEsTCMh6YmZX8sgr471H

ZM7VyTcXQ81J8UVhgb1ak8QTlAfJe2Cwqme53Fu+gxIS99G5oxbQMm5me2KR

TMwBjlt1U4tvYS26qZx7n2xM4YY2E8sEx5wmeW6R732Ir9OaYWxLV8sOioQ4

Qy8g7iKuoOyDebcXQ7px8owpFSxJg71oQP1LLII69MIYWGlTFscWV2onntQZ

Z4prbUToYhgNbV8EnREXVts33BW7jUr4oWQ6zjVeC1NqIpYhZSrzOShR2Tda

2OcY7pO28Kn8JObqSHAU6IzAz1KY2sgEQm66XmJ81S3h+08gsyu7itGUqmmZ

4dTOEHZqIiU2k2OWaSJy4ICrXJEG+LscpIqh+sgaT1kHwXuz9xF1o4KGrubK

VbmGEtdw2tZcTwmKy1ckhOc48g2Mb3nyPuHb+oCPOSBh+582bSTto.ZhC4f2

6SrScg9.zmdnTGlO6Wd5Jlt1.mclFpS0Ubbal60bcANyqyY6rt.sqt2q1pBf

kDPqJbzWWGtZ3JnLmiuUR3UMfU+63XUN8T8ye4blobyl7KWLGIJSXyahxUp7

ZnxURydcYUdxNSVdxm4cBNxS177jO9dX+2yoHWWwjbL6nILAYJ+MQBxM9bGP

zDleLkNI4GWlsYyAYldFmTbX4Re4aj1i5YqmvmukR8QCNX0s4YoYJ1w.CQnN

V0TePsN7DuoaDBDw7NBAi5Ypyni73S13CHtS43CFV5c+ZkRhyRTa8BgoqWHS

ZNb6tj18ggZ0a1u969p5B+AV4cp8W.U8Dmi6ATDeq8x3v+EqWylhvwn4tynP

ggeABJ5jp9Dtl0bauyWM3Jhz5eri64UuVqHhX9VQj8auNJe4PxVlE7jkI57q

d1sxJvUOzAsM88IBWeWU6eeguOkq9MFOvQMiDmp0jUBlzm6Bx8zk68w9Rfix

Etn52B7cp7k.hmK2S2YryR4Y39iPcAEWbbWQgWeHh+32eDbLe+Qf+c19iPcO

guIeHm7bccbnp2zn3gbBOjSV8gbx0WHqZ4DDfG7wSCEn.J.n.fB.JzEJv.T.

PA.E.TnKTfCn.fB.J.nPWnf.PA.E.T.PAsLEb.U.TAPE.UPaREB.U.TAPE.U

PiJ3Cp.nBfJ.pfFUvCTAPE.U.TAMpfKnBfJ.p.nBZTArFDfJ.p.nB5TAHWAP

E.U.TAcp.T1HnBfJ.pfNU.ODDfJ.p.nB5TA77RBp.nBfJnSEf1FAU.TAPEze

Jpg1FAU.TAPEzoBPaifJ.p.nB5TAnsQPE.U.TAcp.z1HnBfJ.pfNU.ZaDTAP

E.UPmJ.ULAp.nBfJnSEfJl.U.TAPEzoBPESfJ.p.nB5TAnhIPE.U.TA8WPLP

ESfJ.p.nB5TAnhIPE.U.TAcp.TwDnBfJ.pfNU.pXBTAPE.UPmJ.ULAp.nBfJ

nSEvNzFnBfJ.pfNU.ZaDTAPE.UPmJ.sMBp.nBfJnSEf1FAU.TAPEzoBPaifJ

.p.nBZTAHsQ.E.T.PAMn.T1HfB.J.nfFT.BaDPA.E.TPCJ.cMBn.fB.JnO7g

2jieHvi633364Ap.nB1kJD3SqpZI.U3LTAOPE.U.TAPEznBtfJ.p.nBfJnQE

DfJ.p.nBfJnQE3fJ.p.nBfJnQEXfJ.p.nBfJnQEnfJ.p.nBfJnQEHfJ.p.nB

fJnQEb.U.TAPE.UPSuyAfJ.p.nBfJnQEf1FAU.TAPEzoBPaifJ.p.nB5TAns

QPE.U.TAcp.z1HnBfJ.pfNU.ZaDTAPE.UPmJ.sMBp.nBfJnSEf1FAU.TAPEz

oBPaifJ.p.nB5TAnsQPE.U.TA8ssQnsQPE.U.TAcp.z1HnBfJ.pfNU.ZaDTA

PE.UPmJ.sMBp.nBfJnSEf1FAU.TAPEzoBPaifJ.p.nB5TAnsQPE.U.TAcp.z

1HnBfJ.pfNU.ZaDTAPE.UPmJ.sMBp.nBfJnQEDPaifJ.p.nB5TAnsQPE.U.T

Acp.z1HnBfJ.pfNU.ZaDTAPE.UPmJ.sMBp.nBfJnSEf1FAU.TAPEzoBPaifJ

.p.nB5TAnsQPE.U.TAcp.z1HnBfJ.pfNU.ZaDTAPE.UPiJvg1FAU.TAPEzoB

PaifJ.p.nB5TAnsQPE.U.TAcp.z1HnBfJ.pfNU.ZaDTAPE.UPmJ.sMBp.nBf

JnSEf1FAU.TAPEzoBPaifJ.p.nB5TAnsQPE.U36TpPyAqOR0+VSJpZ3s75rG

ZZLV2Pb41vGVkDVTT21NpnHbSaK6pXU0wWkDEl2dzcgkqtMNcyGOdmPbjUzu

XAyM3RW4OBW4u6oNBkdL3rrn7K0k6Ka+pR2uMNMIptUF83Ak0CZOJo4nw0zm

rq+zGba+30WV4W10o1zKvqSitW909Dmded5B+fy30rFmldvo4B63zzm5zjS5

zR1wxKVr75vzM59e08vxDYc3FJVa3nxWRZpaeLnTjsOeU62ZkM4K6v8VtNpn

LNM7Hcq5h7nZWTV95n7pBtdKIrpoYN8aZmo2z9mvqcmASeBu1a5Msme+l1eF

7Z9IplMCE1dmx1yPcbe29sMaFL8IJs4yPD+DdsXTl9QNT+llqt+XmniDisjq

oVhOVKYR3zUcQzwZIpoVhLVK4XhkXVvm77M0Ri0m7LoFguEp5wEFZHhs6y1i

aZvjY69r8LtU.y5dsIMKDNVnjk4XpkFak0.SMjyHMjvHWx0BVxjF5DpMZnSL

o+soHwUirLYJxV2yzf6X40tAlZow1Xy0ndFBrPMSWShds2NiyRlz0P6sy3sD

cnxIGhMLE2TDxnq7wL0Rikg3ZReJz.aYIhIVZzkSlPm3VwRF0ohUrj4.2w0M

oQcHaCDgvDrmvFHBgQXOwTLNPiLsPLEi90HSyC5O8b1LXZxTLuVlY59sLc5s

LcRRJxHSSll4vT3ZXRnisOQgQoTXEFnI8yyoSRzznIidRlGbA6YX5wYI5rYI

xrYIyaEX4hMSG7.w10Uq56fOTeabKDbqrDaHKwrkkFZzDBpsrzPoCKH1xRC1

HvJQOil5Cq3SF0MuvFVRX57.vsdCLtgPkwNzLtIneOqTtYB5mXi46iazf.sR

sdGCmFbqmsfQVlLIYKvM0xticpnMgdQsQMFlIzKlMFLOyjblY1XnuLiROvF8

mw3yUpVLiRTkOE05YrQjd93ZqynOiRRK60FaZxj30CkkjqUZ8OaCUfYX2ETa

OCELShkSxbivLHq5GMm2ynOy4SwZTarkoVuQigSAFYJLL0.C+p3wUYi3MEkx

TSrrv1VlZzv5lBIcQMYnqSmkGLYP+o.jXtoISRIM40yqIudd8fMpmDgCZtos

NB0n.9D50jWGu1yzUgdrIeQceFqRy3rj3Y3SVtoi3Yrn9VtjzjgARESwHjLy

zSxHjnr4ZZsnzmQ7cbVxnAD4aKKMXmL1PZdTGSEK8nsjIFxFUHHFM+z1H3Yj

b5ESQVHFYY9IT5XvL7zAchmg.hXFr8Ih3jYHjyNQR9jY3QFgcJkTLCOyHmJW

axL7fQQOQ0b5L7zIQO0jpNCOUVjSUOeFZeSNU87Q9L3wbLIiapM5ikvLashr

RGEr4JGEhYiTyR1x+4nxpQZKiz6oUFQDgZrDRni1Tl3U1XcuHlj7pUhdNF8n

P3vrhsLIMHeaYoAyH2J9jIqIgkryfHomXm5mq8vc6tKJun4hqLwxsgeJq9Yg

9hp+abZ8+kU8eyitKt854UGILe0swkQqZ2sIV9fe8lKvR0NmQd593lQgJs7e

+8++.XvwyyC

———–end_max5_patcher———–

</code></pre>

And finally, the full collection of the text I used in my project, as well as a proper bibliography is available here.