Next I want to talk about Patchwork Girl by Shelley Jackson, and this is not going to be easy or pretty–but neither is the Patchwork Girl.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPnKbegz050[/embedyt]

Last night I got the results of a DNA test that my mother paid for, for a Christmas present. Nothing is better at emphasizing how we are all patchwork than a DNA results report. We’re all made up of recombinant chunks of information, material information or information that materializes, as is the PG, bastard remediation child of Mary Shelley out of Frankenstein. Looking at the illustration of my 23 DNA chromosomes, and especially of the X chromosome that directed me down the path of identified womanhood and all that implies and entails, was strangely gratifying. The human genome or the human program, the writing of being alive. Runtime.

In this video, Shelley Jackson is mesmerizing as she reads her work to the camera. It feels as if I’m witnessing someone who has just been let out of an oppressive situation, or prison. At 2:14 in the second video of her Pathfinders’ session on YouTube, she pauses after reading a longish passage on Mary’s meeting with her female monster, and directs the audience to a fork in the text, a link called “written” and another called “sewn.” The reader can choose: do you want the familiar path of “written” text or the less known path of sewing a bodily text like that of the story? While you must choose, you can return and try a different path, which provides choice, and a kind of freedom.

Before going on, we’ve talked earlier about how the digitization of texts seems to promote the hypermediazation of print, with at least part of the population hyperaware of the material nature of print and books in a new way. I talked about the interest in making bound books by hand and in handmade journals to be written in by hand, often with handmade paper (on this site, with recycled materials) as well. One of the neatest apps I’ve seen is Paper by 53, which allows you to go around the loop again and redigitize and simulate the experience of working on handcrafted paper with simulations of watercolor, oil, charcoal, etc. Jackson chooses writing “for the hell of it” and reads a beautiful, dense passage that describes the sewing of the monster to quilting, a tribute to a traditionally female activity that wastes nothing in the process, and aligns writing with sewing. Then she reads the “sewn” passage which leans into metaphors of writing to describe sewing the monster together. These forked choices seem like a making apparent of the insistence of metaphor to own our actions and spaces of the real, and also of the gap between what is done and what is experienced.

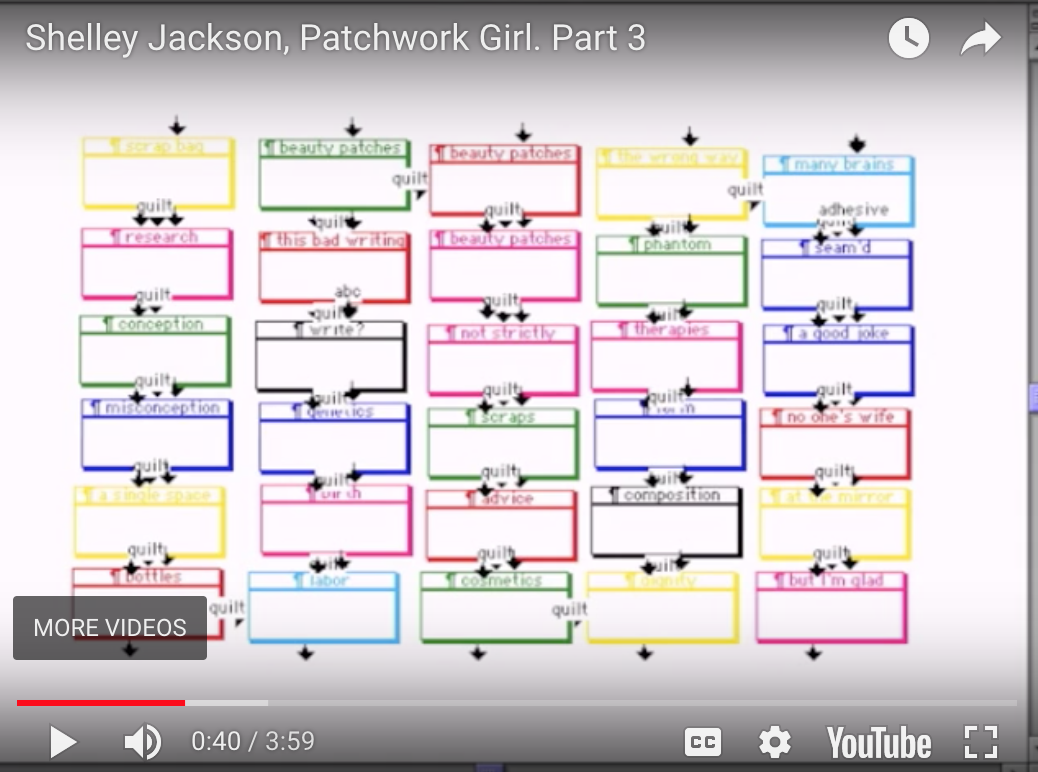

One of the most powerful sequences of the text is the hypertextual image map of the monster in which every body part is linked to the story of its original woman. Each of these women has a life which was limited by circumstances but also filled with some passion or obsession that is now expressed by the monster. They were in hidden pain of one kind or another during life, and in death, they are worn by the monster and no longer hidden. The tongue’s (Susannah’s) story, for example, is one of unbridled desire and expression, through food, drink, and words, and even punishment in the stocks for public drunkenness cannot contain her: “a fishy stew” of gossip, poetry, heresy, and news emerge from the monster’s mouth. After spending time in this graveyard–as the stories are mapped onto images of graves–you emerge with the parts you need to create her.

The quilt section moves away from the analogy of a physical body being brought back to life toward something much more clearly about composing in a digital environment–moving writing front and center out of the shadow of the body. This illustrates Hayles’ description of how pattern/randomness is superseding presence and absence. The original Frankenstein story is not about mutation, but about the constructed presence of an artificial life form, energized by science to simulate life and to have a conscious mind. Jackson’s tale, however, is using the image of this constructed presence to show us something new: the manipulation of patterns held together by data/codes to “sew together” a unified text. And in doing so, it hypermediates human bodies and the condition of being flesh and living, suffering, experiencing, and dying.

Patchwork Girl is also about women’s work. Women’s work is now a focus of pop music such as the rap videos of Cardi B. and the musical productions of Rhianna and Beyonce, and these artists also do not shy away from the woman’s body as a site of work, whether it be by singing and dancing, making videos, dealing with oppressive politics, or dancing in a strip club. Men have always claimed their work as a source of power, and sought pleasure from it when possible, and claimed pleasure from the love, labor, or entrapment of women. Patchwork Girl celebrates the grimy, gritty, material activities of women’s work, celebrates their pleasure, and hypermediates it through a virtual platform of digital work.

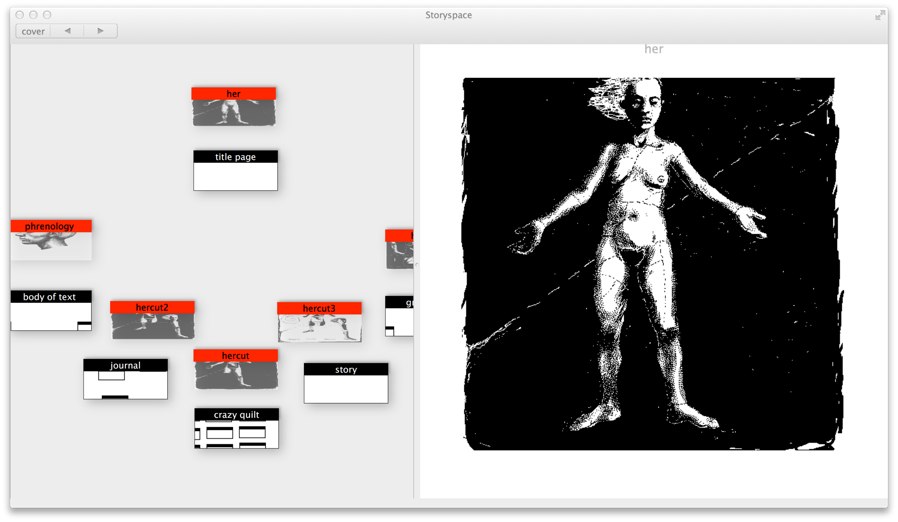

I was able to buy Patchwork Girl!

It was a difficult birth.

Buy it off of Eastgate directly–they have advertised it for compatible with MacOS Sierra. (I have High Sierra.) No PC version. I believed it was going to be shipped on a USB, but after a day, they sent me a download link (after charging me $8 for shipping 🙁 ) In any case, I can now show it in class.

Yay! And it will be interesting to see how/if it’s changed. Will moving the hypertext onto a USB remediated it?

I think they tried to retain the original format, but the code is probably changed–and it still has that slightly buggy feel to it (one of the boxes seems broken).