Aaron Swartz’s experience with the courts is convincing testimony of the fact that all men were not created equal and cannot expect to receive equal treatment. From an early age, Swartz demonstrated a remarkable facility for understanding and using digital technology. His motor skills, exceptional reading abilities, use of his higher cognitive skills, capacity for exploration, and his leadership potential that were recognized from as early as age three, set him apart from others. His parents and siblings, discussed with pride Aaron’s ability to learn how to learn, to successfully interface with technology and to genuinely commit to sharing his knowledge with others. This goal-oriented young man saw computer programming as an excellent problem-solving resource. Therefore, he built websites including watchdog.net and openlibrary.org and made a major contribution to improving technology.

Swartz was undoubtedly posthuman, a characteristic that is explored by N. Katherine Hailes. She articulates concepts of the posthuman view as privileging “informational pattern over material instantiation,” considering “consciousness…as the seat of human identity in the Western tradition,” thinking “of the body as the original prosthesis we all learn to manipulate,” and configuring the “human being so that it can be seamlessly articulated with intelligent machines.” This means that the posthuman body, is directly comparable to computers, cybernetic mechanisms and robots. Because of these talents, Swartz won the admiration of many but was greatly feared by others who saw the possibility of being exposed if certain information was downloaded and placed in the public domain.

When Swartz decided to teach himself and quit school because teachers were domineering, disliked being questioned and showed a preference for pedagogies that relied heavily on memorization and regurgitation, this was a serious indictment against the system of education. I question how is it in the twenty-first century that any teacher could ignore tried and tested teaching methods such as validating students as knowers, modeling critical thinking and higher-ordered reasoning skills and situating learning in the students’ own experiences? Nevertheless, Swartz left, engaged in his own learning, found his niche and developed his skills using digital technology as a tool for information sharing.

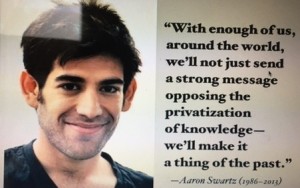

His growing awareness of the negative impact of capitalist ideology on a society in which large wealthy corporations exercised control over the fundamental right of people to access information about issues that affected their lives, contributed to his decision to advocate for freedom of information, in its most meaningful sense – education of the masses. Those who admired Swartz and supported his ideals included the owner of the world wide web, Tim Berners Lee and his close friend Lawrence Lessig who contended that there was a new way to define copyright so that only some rights would be reserved. This would afford the public access to material (that did not have rights reserved). Swartz was outspoken about his views that the creative process involved building on something that had been created before, further, that free and open communication had been guaranteed under the First Amendment. He stated:”Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves.”

He was therefore convinced that data stored by organizations such as JSTOR, were not serving a useful purpose if they remained hidden from the public. Additionally, Swartz suspected that some of the stored data might uncover corruption. As a result, he made a fearless decision to engage in what he considered civil disobedience. He noted that the public had limited access to important legal public records. For example, in order to get certain documents, users were compelled to download PACER, which required them to first use a credit card for payment. He questioned why, government grants and tax payer’s money were being used to pay for intellectual journals, yet the public still had to pay again if they wanted to access these materials? Why should corporations amass huge profits from those who could afford to pay and exclude those who did not have the means?

Swartz made a decision to ignore the copyright laws which protected the corporations, and download files by going into the basement of MIT and attaching the necessary equipment. This was a decision to boldly confront the government, MIT and JSTOR. What happened next, could be described as a ‘knee jerk reaction.’ Such a reaction is aptly explained by Frantz Fanon: “Sometimes people hold a core belief that is very strong. When they are presented with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted. It would create a feeling that is extremely uncomfortable, called cognitive dissonance. And because it is so important to protect the core belief, they will rationalize, ignore and even deny anything that doesn’t fit in with that core belief.” The establishment was firmly of the view that it was a criminal offense to hack into data protected by the copyright laws. The other concerns were of no significance to them.

Ironically, the mission statement of the US Copyright office is: “To administer the nation’s copyright laws for the advancement of the public good, to offer services and support to authors and users of creative works; and to provide expert impartial assistance to Congress, the courts, and executive branch agencies on questions of copyright law and policy.” Swartz must have been painfully aware of the contradiction that existed between these words and his reality.

The developments that ensued and were made public, proved tragic. Swartz was subjected to ‘cruel and inhumane treatment.’ This included an FBI stake out near his family home, the involvement of the Secret Service, arrest and physical abuse by the police, intimidation and threats, the offer of a plea bargain in which Swartz should plead guilty, and in exchange serve 3 months in jail, 1 year’s probation and forego computer access. Swartz did not consider himself a criminal and would not accept being banned from computers, therefore he refused the plea deal. He fought, with solid support from the public, and stopped the law entitled SOPA (Stop Online Piracy Act) from being used against him.

Just when he thought victory was in sight, the authorities increased the felony counts from four to thirteen, eleven of which were based on the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which could function like a ‘one size fits all.’ Some were optimistic that Swartz could win that case. However, he realized that he was up against the politics of fear and anger which caused the courts on July 14th, 2011 to indict him on a range of counts for a prison sentence of up to 35 years and fines amounting to 1 million dollars.

Aaron Swartz was broken and exhausted. He was found dead in his Brooklyn apartment in 2013 without making use of the opportunity to fight back. The coroner determined that Swartz had committed suicide. Few have accepted that explanation, and Aaron’s father contends that the government killed his son. It is clear that Aaron was given a longer prison term than someone who committed murder. No one can say for sure exactly what Aaron was going to do with the files he downloaded. All we do know is that he insisted that the law was never intended to stifle creativity or free speech. Was the action taken by the courts an acceptable way to create a deterrent? Few can accept this argument. The message the courts appear to have sent to us is that they were prepared to sacrifice Aaron Swartz on the ‘altar of expediency’ in order to protect government and big business from possible negative exposure.

Aaron’s views as expressed in this video, leave no doubt that his main concern was for the general good of society and their right to information and free speech.