Hannah More’s “The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain” was widely known and satirized in 19th-century England.

As a vestige of a Victorianist, I’ve often found ephemera studies to be fascinating. This began, I think, during my MA when I was studying the readership and publication history of Christian tracts in 19th-century England. Leah Price’s How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain had just come out, and in this work, she specifically examines the ephemeral quality of Christian tracts, portraying them as widely produced and distributed (by a pious upperclass) and then less widely read (by a lower class, involuntarily recipients). Yet, these texts still made a significant impression in Victorian culture; references to more “popular” tracts were widely known and easy to identify. In their rapid spread and equally rapid discarding, the tracts might be thought of as both ephemeral and viral.

Ephemera and the quick surges of popularity they produce become even more pronounced when observed in digital form. Mimicking our own fleeting interests and the identities they help to construct, digital ephemera seems equally tied up in changes, nostalgia, and sometimes-intentional erasure.

In “Memorial Interactivity: Scaffolding Nostalgic User Experiences,” William C. Kurlinkus considers how nostalgia, ephemera, and ritual function (and how they might function) in digital design. Expanding on these phenomena, he demonstrates how user engagement peaks with their knowing (or unknowing) inclusion. Memes and the Ice Bucket Challenge are among his list of examples that “act as a form of collective memory, providing a structure and set of values that are enacted through replication and upon which individual memory might improvise.” Part of their benefit is how they appeal to the often-competing human desires of community and individualism. “[T]he most viral of the viral is virality that personalizes,” he goes on to say. “The nostalgic impossibility of pure replica—the gap between original video and the copies—makes the meme personal, meaningful, and (ironically) possible” (278).

As I read through Kurlinkus’s chapter, I was struck by a number of connections—frequently realizing that my own experiences reflected the ideas he’d put forth. This seemed especially true in my reflections of using YouTube.

While Kurlinkus cites examples of “viral nostalgia” that follow the spreading of digital texts from one person to another, appealing to individual’s memories, I see several aspects from YouTube as producing what might be thought of a different form of viral nostalgia—the reproduction of memories within a single user (virality within one “host”).

Stony Brook English Professor Elyse Graham told me upon our first meeting last year that humanistic influence is so pervasive in the digital world that it’s almost invisible. So many of the terms and functions that we use regarding our use of computers points to vestiges of real-world meaning that have been remediated: we dump unneeded files into a trash can on our desktops; our desktops are vertical screens; and even screens and windows are terms that were first used to reflect objects we look at or through in the real world. Memory is a similar term, and its digital form is nearly inextricable from its real-world equivalent.

I was FaceTiming a friend the other day; I hadn’t talked to him in a few months, and when he asked me what was new, I casually opened up my YouTube’s history without even thinking about it. Scrolling back, I noticed Dream Daddy tutorials, the music video for a song called “Elysium” by Bear’s Den, and a preview for the movie Every Day. I told him that I’d been working on a project for school that centered around the video game, recommended that he listen to the band that I’d only recently come across, and asked if he’d heard of the movie—offering him a quick synopsis of the trailer and informing him that it’s based off of a book by a favorite author.

I don’t always do this (refer to YouTube for a shortlist of my own recent memories), and I didn’t consciously think about it as I pulled up the history page on my computer, but this experience made me think about the ways in which YouTube does facilitate and appeal to nostalgia.

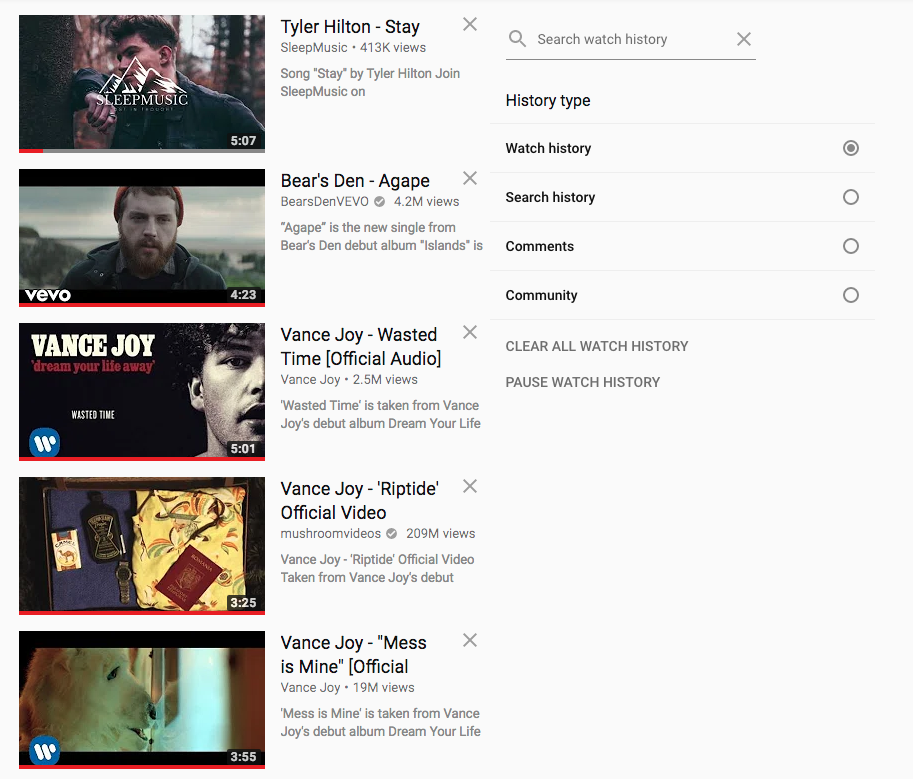

Screenshot of the “History” page on my YouTube. It even allows you to search through your watched videos.

This reflects Kurlinkus’s notions of viral nostalgia in that, while YouTube’s “History” feature and its main-page equivalent (suggestions beneath the heading “Watch It Again”) are simply based off of algorithms and cookies, it’s personalized to each user and calculated to appeal to their individual memories and experiences.

To provide another example, I set out to scroll through my history on YouTube to see what I’d watched at this time last year. My computer has a funny way of mimicking my own memory, however, in that the further back I went, the choppier things got. It took longer to recall those older specifics, and at some point, I lost interest in the act of recalling altogether. In the process of sifting through my history, however, I got distracted by a series of videos from last summer, and they adequately serve my purpose. They were a number of music videos for unapologetic pop songs that coincided with my trip last August to London. During that trip, the friend I stayed with played these songs on repeat while we got ready to go out every evening. Looking at them now, I’m well aware of the nostalgia that YouTube has personalized-though-digitally-calculated for me.

What I find particularly interesting is the “X” that accompanies each of the videos in the screenshot above. While appealing to my sense of nostalgia, YouTube offers the intentional erasure of certain memories as well.

Kurlinkus ends his chapter by considering the benefits, rhetorically, of creating appeals to nostalgia through digital content. As nearly everything on the internet seems to fall under the category of ephemera, this seems especially relevant. Online texts are inherently ephemeral; already, my first posts on this blog have sunk to the bottom of a lengthy feed, ready to fade from view. Coming up with ways to remind your readers/viewers/users of past content and their connections to it keeps it relevant for at least a little while longer.

March 20, 2018 at 12:05 pm

The caption on your photo of the Victorian tract caught my eye–that is was widely satirized (by the upper class or the lower?) What is the role of satire in perpetuating interactive nostalgia? I think we tend to associate it with sentimentality of one kind or another, but even the Ice Bucket Challenge, despite the “do-good” aspect of the movement, was marked by a snarky upstaging of how ridiculous the iterations could be. The ephemeral nature of the texts seems to make them less inviolable than say The Bible or a studio film protected by DRM.

March 20, 2018 at 3:12 pm

I also think that the “X” Youtube provides on your previously watched videos is interesting. You can curate your own viewing past, which may also be an active version of nostalgia. Kurlinkus noted that just by creating memes or videos as part of viral nostalgia, users are already imagining a future self that can and will return to these memories. When we “clean up” or previously viewed video lists (maybe I need to delete the multiple views of “Bet On It”?), we imagine a future where we can return to this history list and feel proud of our great taste as well as nostalgic.

March 20, 2018 at 5:00 pm

Hi Jon, you make great points about the ephemeral quality of social media posts, and the calculated targeting of YouTube’s analytics. I’m always mildly surprised when similar videos turn up as suggestions. Your post makes me want to scroll back through my FB and check out my online memories!