Identity & Las Castas

Guatemala was a “multiethnic, multicultural, and multilingual country” (Soechtig, 1) prior to the arrival of the Spanish. Home to numerous distinct indigenous communities made up of the descendants of the Maya classical period, Guatemala has always been a place of rich cultural and historical importance. However, upon the Spanish arrival and conquest of the territory, as was the case for all of Spain’s new colonies, social stratification based on racial categorizations became a central feature of the colonial project.

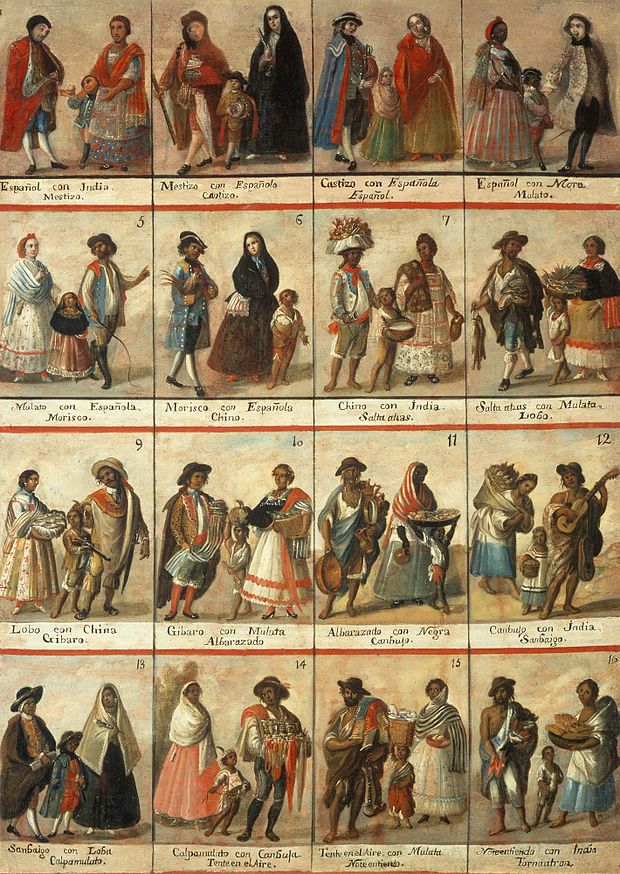

Racial mixing ensued as Spanish men intermingled with indigenous women. As a result, new racial categorizations were created in order to maintain a social order in which the Spanish remained at the top–system of Las Castas was created. By means of this new categorical system, the Spanish sought to create a clear and immutable social hierarchy based on apparent level of [white] European lineage. Those of mixed lineage fell in the overarching category of Mestizo, with more than twenty subcategories based on the level of mixing. Meanwhile, white Spaniards were at the top, and Indigenous and enslaved Africans at the very bottom of the social pyramid. As part of the Colonial project, Spain relied on racial mixing to “create” subjects that would see the crown as a legitimate sovereign. However, despite the apparent stringent nature of this system, the Spanish created a provision so that lower castes were able to purchase “whiteness” by means of the “Gracias al Sacar” decree. Unfortunately, as quoted in a 2020 essay, “The Castas System,” “those who did attain a higher social status because of the decree often did not speak out against the system. This meant they left behind those in their own social class furthering the power of the Casta system” (Twinam).

“in Guatemala today, ‘indigenous’ and ‘ladino’ are typically understood as mutually exclusive categories. Being indigenous means belonging to an ethnic group with roots in the pre-columbian past, such as the Maya or Xinca. Being ladino is, in the modern usage, an identity of negation: that is, not indigenous, whether one arrives at that identity through full or partial descent from Europeans and/or (often less admitted) from Africans, or through abandonment of indigenous culture and language. ‘Indigenous’ is associated with conquest and internal colonialism, while ‘ladino’ is associated with full citizenship in and affiliation with the Guatemalan nation-state. The bifurcation of contemporary Guatemalan society into these opposing camps is often belied in people’s daily lives. Nevertheless, it reflects and feeds into undeniable ethnic tensions that were exacerbated during the country’s recent civil war.”

As such, the status of the: indigenous Maya, Xinca [Non-Maya], and Garifuna communities in Guatemala continue to be second to the “mainstream” Mestizo & White minorities whose grip on the state’s political, social, and cultural institutions remains strong. Even after thirty-six years of civil conflict in which indigenous-backed left-wing guerrilla groups were in direct opposition to the Guatemalan conservative government, the status of Indigenous peoples in the country has remained virtually unchanged despite the human rights abuses and evidence of genocide during the armed conflict. For indigenous Guatemalans, full citizenship remains an aspirational goal–even after a road to prosperity for ALL Guatemalans was promised after peace was signed in 1996.

See The Garifuna for links and information about Guatemala’s Garifuna population, including their origin, culture, and fight for survival in Guatemala.

__________________________________________________________________________

Further reading:

Guatemala, UNICEF. “Look at Me: I’m Indigenous and I’m Also Guatemala – UNICEF Guatemala.” Medium, UNICEF Guatemala, 23 Jan. 2018, unicefguatemala.medium.com/look-at-me-im-indigenous-and-i-m-also-guatemala-2ae157f19646.

Hendrickson, Carol. “Guatemala – Everybody’s Indian When the Occasion’s Right.” Cultural Survival, June 1985, www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/guatemala-everybodys-indian-when-occasions-right.

Sources:

College of Wooster. “The Casta System.” College of Wooster- Latin American Voices, 4 May 2020, cowlatinamerica.voices.wooster.edu/2020/05/04/the-casta-system.

“Guatemala Population 2022 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs).” World Population Review, worldpopulationreview.com/countries/guatemala-population. Accessed 2 May 2022.

Söchtig, Jens, et al. “Genomic Insights on the Ethno-History of the Maya and the ‘Ladinos’ from Guatemala.” BMC Genomics, vol. 16, no. 1, BioMed Central, 2015, pp. 131–131, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1339-1.

Twinam, Ann, 1946. 2015. Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.