It’s undeniable that inequality persists in American storytelling. Our new high school curriculum [one made by big business] attempts to explore this inequality. There is even a unit on feminist criticism chock full of stories and films to explore (Kate Chopin’s “Story of an Hour,” My Fair Lady, Pygmalion). I wanted something more modern, so I substituted the pre-scripted lessons for ones my own, ones that explored Oates, O’Connor, and Atwood. We looked into modern issues that affect female empowerment and opted for more controversial topics. I even had the students explore films using the Bechdel test. For anyone who is not familiar, I’ll briefly outline it below. Alison Bechdel is an American cartoonist who grew to fame from her cartoon series, Dykes to Watch Out For. One cartoon in particular explored feminist film theory and grew to create a three-question test to expose the slanted storytelling in American film.

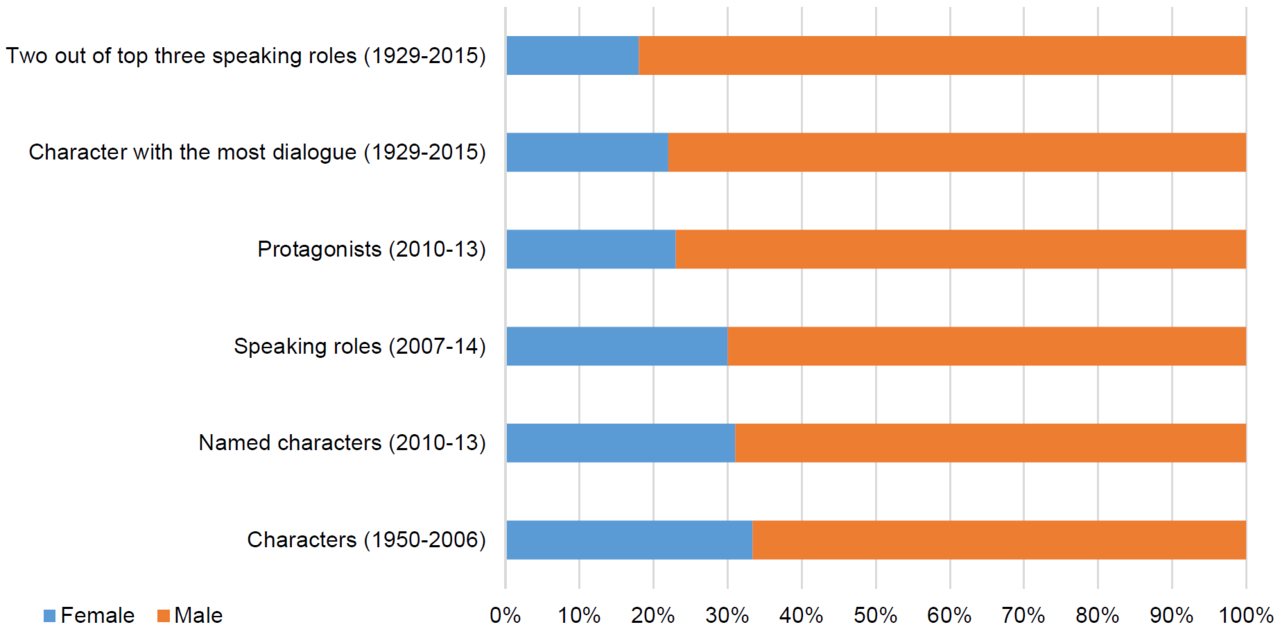

Some people have used to this to put together real data, and the results are astounding. Women have little voice in our filmmaking. This point only further justifies work like Hidalgo’s.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Female_and_male_characters_in_film.png

In researching talking points for this blog post, I stumbled upon this evaluation (below) for films and have since used it to create a new assignment for my seniors. I also used it to prompt my discussion of the film.

I chose to analyze Pretty in Pink for three reasons–(1) Andie Walsh is one of my favorite female characters in film, (2) it passed the Bechdel test, and (3) it was available on Amazon Prime.

The opening sequence of moving images sexualize the teenage girl (Molly Ringwald). we watch her put on her tights and zipper up her skirt flashing a little bit of her lacy pink underwear. If the goal was to show her love of fashion and the color pink, many other options could exist (think opening sequence of Clueless with Alicia Silverstone) only to move to a shot of her in a submissive role; she functions as her father’s alarm clock and servant all at once as she pours him coffee, wakes him up, opens his blinds, and reminds him of the basic functions of an adult ( showering, job interviews). The first two minutes and forty-five seconds of the film have locked our female protagonist into a doomed patriarchal role.

Even when we buy into a sincere moment between father and daughter at 3:45, watching him commend her for her creativity and drive in the fashion world, he quickly follows it up with a mocking comment about ruffling his white tank. Underhanded from the get-go, John Hughes does not give his Andie Walsh anywhere to move in this patriarchal suburb. She becomes the victim of the male gaze in the opening sequence of images walking into the school where first Blane and then Duckie validate her existence through their eyes. The viewer does not see Andie’s experience as he/she/they would be able to see it while watching a film directed, produced, and edited by a woman like Camera Obscura.

Shortly thereafter, the female characters in the classroom (peers and teacher) combine to create an awful commentary on women. The teacher–talking about the male politicians in charge of running the country and the decisions they made–fails to connect the information to these female students in an inspiring way. As she drones on, the blonde female students exchange snide comments and dirty looks, completely disengaged from the weighty information being discussed.

The film does not suggest that women are powerless. Take the TRAX manager, Iona. When Andie sees Blane, Iona yells at her male partner over the phone: “I cook for you, I do your laundry, I sleep with you, now you want a ride to work?” Sure, Andie’s father needs to see “the woman about the job,” Iona is the manager at TRAX, and the social studies teacher is a woman. Yet, the women in Pretty in Pink (regardless of the facade of power) still exist and struggle in a world dominated by men.

https://getyarn.io/yarn-clip/5c1b68cd-dfe4-4ba5-8692-308660a081fb

Andie’s mother–the one the father says “split”–most likely leaves as a result of the suburban patriarchal oppression, but through this male conversation between Duckie Dale and Jack Walsh, she is vilified by the chain-smoking, beer-drinking unemployed father. Andie’s mother is not without fault, to abandon a child is a difficult act to forgive, but I mention this scene as a way of illustrating how confining the social expectations of Hughes’s Chicago suburb is: rather than help her daughter manage the struggles of growing up in suburbia, she leaves.

Even in Andie’s pseudo-happy-ending, we see evidence of Hughes’ chauvinism. Andie gets a happy ending that will–on the surface–stop the bullying and lead to self-acceptance. However, I venture to say that upon closer analysis, the ending potentially move her into a new wealth bracket since her father (the only other option for financial freedom) cannot do so. This story in effect is no different than Cinderella really. Andie is her father’s daughter until she is Blane’s girlfriend. Her happiness and fulfillment is connected to Blane’s acceptance and validation of her. This assignment helped me to see that the Bechdel test can provide false positives. Not only are Hughes’ women confined in traditional, submissive roles by men (Jack [as father], Steff, and Blane), but his women also create pain and misery for the poorer men who pine over them (Duckie and Jack[as husband]). Marx wouldn’t be too happy with this ending either.

In my version of the ending, Andie would make the dress to wear to prom, look at herself with self acceptance in the mirror, and then dance the night away with Iona: a true tale of female empowerment.

After I analyzed this film, I thought about other recent films I’ve watched: Us and Parasite. Though these films show women in a more positive light, they are still bound by a financial system that does not allow them true freedom. They do not accurately tell the story of the female experience the way Hidalgo suggests. Moreover, the crew (thanks to IMDB) does not have adequate female representation to even suggest this misrepresentation. I now feel more able to teach feminist film theory to my classes of seniors to show them the depth what needs to be down in American film to truly tell the story of the female experience.

I guess you could say both PiP and Parasite (I have not seen Us) are constrained to some degree by the patriarchy in which they are set, but I think something very different is going on with Parasite. The level of self-awareness of the director is lightyears from John Hughes. I like his movies, too, especially The Breakfast Club, but he’s very settled and to a degree complacent in his sexism, I think. For one thing, he’s aesthetically in love with the male gaze. I didn’t get that from Parasite. I felt like when it occurred, in was in the function of storytelling. The poor females in the story, who would be the counterpart of Andie, were definitely operating subversively in ways that Andie would never approach, nor did she have any reason to–PiP is a romance, not a political satire. I’m sure you know that, but I think it bears thinking about what female representation in a film is IN THE SERVICE OF–and I think that is implicit in your “false positive” of the Bechdel test here, too.