Kelp forests occur in cold, nutrient-rich water and are among the most beautiful and biologically productive habitats in the marine environment. They are found throughout the world in shallow open coastal waters, and the larger forests are restricted to temperatures less than 20ºC, extending to both the Arctic and Antarctic Circles. A dependence upon light for photosynthesis restricts them to clear shallow water and they are rarely much deeper than 15-40m. The kelps have in common a capacity for some of the most remarkable growth rates of photosynthetic organisms. In southern California, the Macrocystis can grow 30 cm per day. Because cooler waters are so important, ocean warming is a major threat to kelps throughout the world. Warming events in recent years, known as marine heat waves, have had strong negative effects on kelps from the west coast of North America to Australia.

Infrared Air Photograph Showing Kelp Fronds at Surface, in red. Photograph by Charles Simenstad

Kelp forests are very productive and support areas of high plant biomass. This is an infrared-sensitive air photograph, taken with a view towards the shoreline; chlorophyll is visualized as a “false color” red. The intense red at top indicates rocky benches covered by the seaweed Hedophyllum, whereas the wispy red towards the bottom represents subtidal kelps.

Alaskan Kelp Forest. Photo by David Duggins

This site is in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. Cymathera triplicata (foreground); Alaria fistulosa (rear). Kelp forests in the eastern and northern Pacific commonly have complex three-dimensional structure, with many coexisting species. As in coral reefs, shading is a major mechanism of intra-specific and interspecific competition.

Laminaria longicarpa in New England. Photo by Jon Witman

Kelp forests on the east coast of North America have fewer species but often are quite lush, and support rich communities of benthic invertebrates. They range southward to Cape Cod and occur only sporadically southward to the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. Urchins are important grazers and may reach densities sufficient to eliminate the kelp forest.

Alaskan Kelp Forest. Photo by David Duggins

This Alaskan kelp forest site is dominated by Laminaria groenlandica (foreground). If urchins are relatively sparse and disturbance infrequent, this species tends to take over. It is a perennial, and shades out other species, including the annual Nereocystis luetkeana, which can grow to the surface, if it can get a start from the bottom. When Laminaria is sparse this is possible, but when it is very dense, thalli shade out newly established sporelings of Nereocystis.

Nereocystis luetkeana – Bull Kelp Stand. Photo by Charles Eaton

Nereocystis luetkeana often dominates northeastern Pacific kelp forests. It has a long stipe that is attached often to a small rock and is kept aloft by a gas-filled float. The fronds extend from the float. This makes for a very unstable arrangement and strong storms often uproot the plant. This kelp is an annual, so more low-lying perennial seaweeds can take over simply by outshading Nereocystis when the sporelings begin to grow from the bottom.

Nereocystis luetkeana Forest at Surface. Vancouver Island, British Columbia

In the Pacific northwest, subtidal kelps are dominated by Agarum fimbriatum, a leafy laminaria-like plant. Their dominance may relate to their high concentrations of secondary compounds that defend them from urchin grazing. From the surface, however, you will probably more likely notice the enormous fronds and floats of the bull kelp, Nereocystis luetkeana.

Nereocystis luetkeana

This photo gives you an idea of the size of this kelp. Most impressive is the rather tiny holdfast (lower left), which is usually attached to a cobble. The large fronds spread along the surface, gathering light energy for photosynthesis, and are held afloat by the bulbous float, seen at the base of the fronds. Owing to the combination of a float and a flimsy holdfast, a strong storm can rather easily uproot such a kelp, and shorelines are often lined with stranded kelps.This plant is usually an annual!

Agarum fimbriatum

This kelp, Agarum fimbriatum, as mentioned above, often dominates subtidal hard surfaces because of its high polyphenolic content, which deters urchin grazing. Note the diminutive holdfast.

Model of Alaskan Kelp Forest Succession. Courtesy of David Duggins

This is a model of succession in an Alaskan kelp forest. We start with a dense population of urchins (top), which keep the kelp from recruitment. Following the death of the urchin population (from disease or starvation) we get a diverse forest with species at many levels. The very upper story Nereocystis is an annual plant, however, and it and other species are slowly displaced by Laminaria groenlandica, which shades and inhibits the growth of newly arrived spores.

Barrens With Abundant Urchins. Photo by David Duggins

Dense urchin populations graze kelps efficiently and leave a low-lying turf, dominated by red algae. Kelps may not recolonize until urchins have died off, owing to disease or a strong storm. When kelps are rare, some urchins adopt a “roving” habit, which ensures that kelp recruitment is poor. When kelps are lush, many urchins keep to crevices and capture drift algae on oral tube feet. As a consequence, the urchins do not affect kelp plants very much.

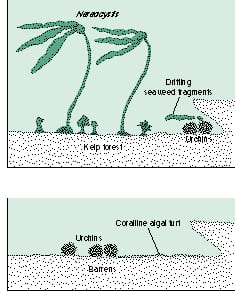

Kelp Forests – Two Alternative Stable States

Two alternative states in kelp forests, as conceived by Harrold and Reed. At the top we see luxuriant kelp growth. The urchins live in cracks, presumably to avoid predators, and catch drifting fragments of seaweed on aboral tube feet. Below we see a barrens, which occurs when urchins are more abundant and kelps are grazed down. In order to feed, urchins must rove about and therefore maintain the bottom in the barrens state.

Hard-Bottom Invertebrates, Alaskan Kelp Forest. Photo by David Duggins

Kelp forests are rich in animal species, as shown by this colorful and rich bottom of epibenthic invertebrates. David Duggins and colleagues found that the large number of suspension feeders found on kelp forest bottoms can be associated with kelp detritus, by means of similarities in the abundances of a number of stable isotopes. The reason for benthic abundance may also relate to the concentrated settlement of planktonic larvae beneath kelps, where water flow is relatively more sluggish than in more exposed hard bottoms. Research by Duggins and colleagues demonstrated that suspension feeders such as mussels and serpulid polychaetes grow well when fed particles of kelp.

Sea Otter, Enhydra lutris, bringing urchin prey to surface. Photo by James A. Mattison III

Sea otters exert strong control on kelp forest food webs. By feeding upon sea urchins, otters reduce the intensity of grazing and allow kelps to develop dense populations. Sea otters bring urchins, abalones, and other benthic animals to the surface and often smash them on their chests with the aid of a rock. Sea otters are also important potential predators on crabs in west coast sea grass beds, and can promote sea grass recovery. Sea otters were once widespread, from the Aleutian Islands to southern California. But hunting eliminated most of them. They are now protected and are recovering but slowly. They can be seen easily in the vicinity of Monterey, California.

Sea Otter With Greenling. Photo by Charles Simenstad

While sea otters often dive to hunt epibenthic invertebrates such as urchins, they also hunt and feed upon small and medium-sized fish. These otters do not have a thick layer of blubber like cetaceans, and must constantly preen their fur to maintain an airy insulated layer of fur, in order to reduce heat loss.

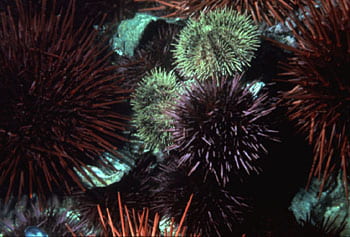

Pacific Kelp Forest Urchins. Photo by Paul Banko

This lovely photograph shows the three common urchins found in eastern Pacific kelp forests. Red = Strongylocentrotus franciscanus; Purple = Strongylocentrotus purpuratus; White = Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis.

Starfish, Solaster Sp. Photo by Paul Banko

Asteroid starfish are abundant in kelp forests and are important predators of benthic invertebrates such as urchins. Locally abundant starfish predation is sufficiently intense to eliminate urchins and to allow patches of kelp to grow. The rise of sea star wasting disease in the Pacific has had strong impacts on benthic food webs because seastars are major predators of sea urchins. The loss of sea stars (over 20 species) on the west coast of North America has had a cascading effect on kelp forest ecosystems. Urchins may explode in numbers and decimate kelp forests. On the other hand, some have speculated that urchins may be exposed to disease.

Purple Sea Urchin Aggregation. Photo by Charles Eaton

These aggregations cause the appearance of gaps, creating a patchy landscape in a kelp forest area. Urchin behavior is connected to kelp community structure by a fascinating feedback loop. Food abundance affects urchin feeding behavior and feeding behavior, in turn, may determine the pattern of kelp recruitment.

Alaskan Kelp Forest. Photo by David Duggins

The word forest is very appropriate for eastern and northern Pacific kelp habitats. In many cases, a surface canopy is present. Kelps such as Macrocystis and Nereocystis have floats that keep fronds at the water surface. Several other distinct vertical layers may also be present.

Macrocystis Forest, California. Photo by Carol Eunmi Lee

In Californian kelp forests in open water, Macrocystis pyrifera often dominates. Like Nereocystis it can grow several cm a day and extends many meters from the bottom towards the surface. Because of this lifestyle, M. pyrifera forests greatly alter the local hydrodynamic regime, greatly slowing currents. This combined with resident planktivorous species turn such kelp forests into filters, greatly reducing barnacle larval recruitment on adjacent rocky shores. Such kelps are often uprooted during strong storms. Unlike Nereocystis luetkeana, Macrocystis pyrifera is not an annual.

Climate change is a great threat to kelp forests, because kelps are basically cold-water species. In Australia, kelps have been in decline owing to warming of waters, and climate scientists have predicted great declines in southern Australia kelp forests in the next few decades. Warm waters on the Pacific American coast has caused thermal stress and reduction of kelps off the coasts of Washington to California. Combined with temperature-related sea star wasting disease, kelp forests are under dire threat. Imbalances have developed, especially explosions of urchins, which overgraze kelp forests.