By ARIEL KAMINERFEB. 16, 2014 – New York Times

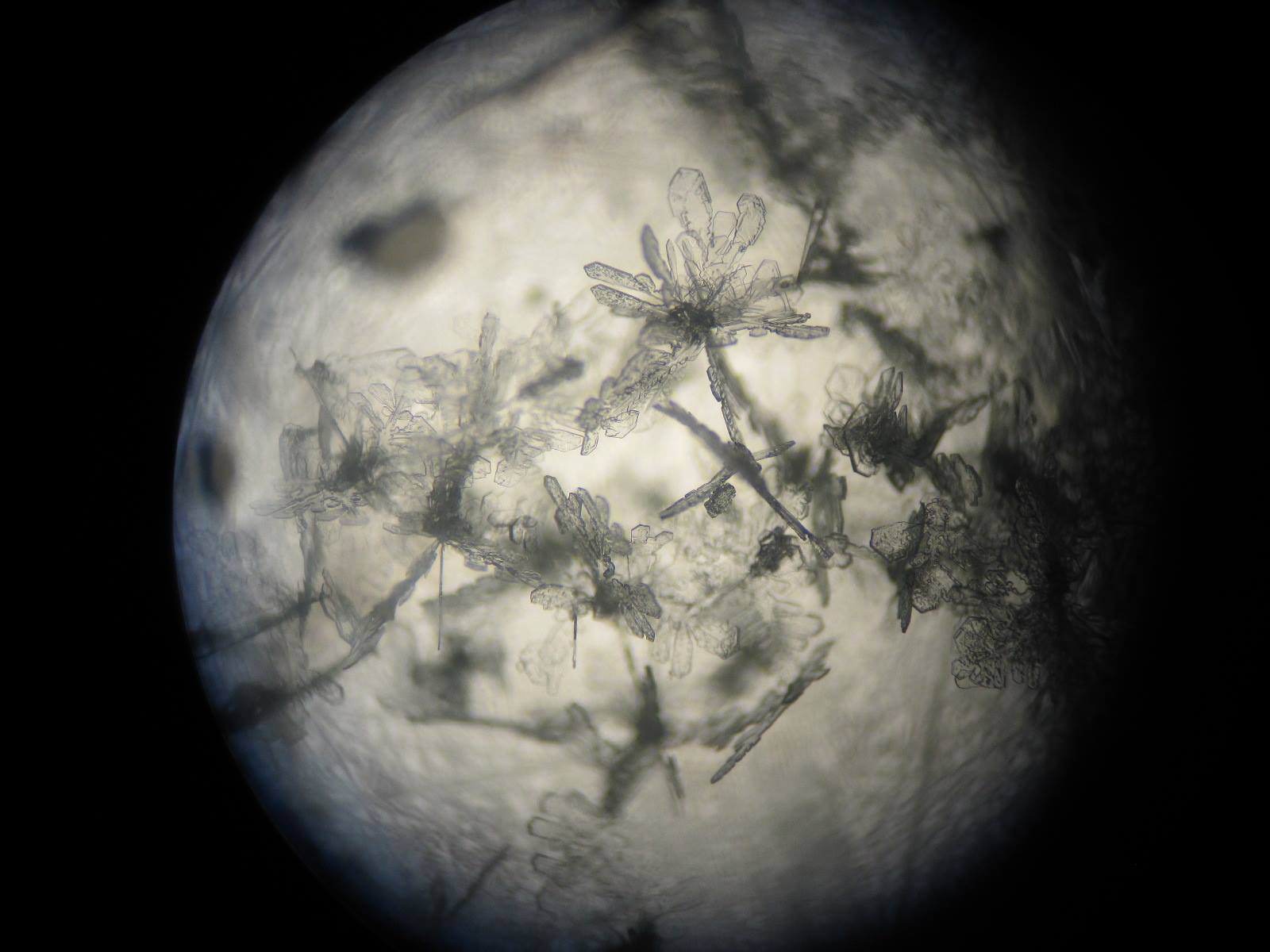

Brian A. Colle woke up at 1 a.m. on Thursday and headed out into the snow. Using plates of glass he had been storing in a freezer in his garage, he collected snowflakes for analysis with a powerful microscope.

Back-to-back storms have made for a lot of night shifts this year, said Mr. Colle, a professor of marine and atmospheric science at Stony Brook University. But he is not complaining. “We’re always looking for good data sets,” he said, “so we’ve been lucky.”

Lauren Nash, one of the younger scientists at the National Weather Service’s New York office, has taken to stashing an air mattress in the trunk of her car because she and her colleagues have to roll into work before the storms do, and that can mean sleeping in an equipment room. “It can be hard, especially when we all have lives and families outside work,” she said. Her friends do not always believe her when she says she has to cancel dinner plans. “They’re like, why? Well, there’s weather coming in.”

The winter of 2014 may not set records for temperature or snow. But the relentless cycle of snow to salt to slush may have finally exhausted the region’s good will, to say nothing of its footwear supply, and proved the maxim about how everyone complains about the weather.

But there are people who do something about it. Meteorologists in the area have been working long hours, poring over data collected by satellite and processed by vast computers. Their colleagues out in the field have scrutinized the tiniest ice structures for clues about future storms. All of them have burned the midnight oil, then fallen into bed — exhausted, and in some cases freezing — only to wake up and start the whole thing over again the next day, or the next week, through a month and a half of unusually intense storm activity.

“This has been an extremely active winter weather season, and we’ve had much higher snowfall than usual,” said Gary Conte, who also works at the National Weather Service. “More than twice the average snowfall, with Central Park measuring more than 50 inches where the normal snowfall is about 25 to 26. Has it created stress on the meteorologists, the people who forecast? It certainly has.”

Their work got a bit more stressful last week, when Mayor Bill de Blasio,taking heat for his decision to keep schools open during Thursday’s storm, appeared to blame the National Weather Service forecast. He was quickly mocked on Twitter by Al Roker, and I. Ross Dickman, the Weather Service’s meteorologist in charge of the New York region, noted that its Wednesday prediction deviated very little from what actually happened the next morning. “I think we had an outstanding forecast,” Mr. Dickman said. “The state of the science really doesn’t get much better.”

That science has grown much more accurate and much more complex in recent years. It begins with huge troves of data fed through a variety of sophisticated analytic models. Adam Sobel, a professor of earth and environmental sciences at Columbia University, points out that this “big, automated, computationally intensive nonhuman process that produces the raw material of the forecast” still requires human beings to evaluate the results and turn them “into an actual prediction that can be communicated to people.”

Each day the New York office of the Weather Service launches two weather balloons, collects data from government sources as well as 1,500 volunteers across the region, and records observations from right outside its station at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Suffolk County, for forecasts that it releases every three hours. Extreme weather, like hurricanes and blizzards, increases the workload in the office and — as the scientists say they know only too well — the stakes for the decision-makers in the world beyond.

The mood in the office is friendly, staff members say. But working hard on a prediction, only to have it bump up against someone else’s — perhaps rendered with a different model, or with a broader data set — can be tense. “Sometimes you feel like it’s your forecast,” said Ms. Nash, who earned a bachelor’s degree in meteorology from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Arizona. “But when you’ve been in this industry long enough, you realize it’s your office’s.”

David Novak, chief of the development and training branch at the Weather Service’s Weather Prediction Center, says that in addition to pushing the predictions further out into the future, meteorologists hope to make better guesses about how many inches of snow a storm will make.

That is the challenge that brought Professor Colle into the snow in the first hours of Thursday morning. Despite the sophistication of many analytic tools, he said, the formula to predict snow accumulation is surprisingly crude: One inch of rain is taken to equal 10 inches of snow.

The storm last Thursday showed how unreliable that measure was: During the first four or five hours, he said, a steady snowfall produced just an inch or so of accumulation. Then three or four inches piled up in the next hour alone. The reason may have to do with the structure of the snowflakes, and current models have little ability to predict that. The samples he gathered in those chilly hours outside his garage may help.

“It’s been a good season, obviously,” Mr. Novak said. “We’re getting a lot of good data.”

The end, however, may at last be coming into view. “We’re actually going to get a little warmer so hopefully that’s a sign that these big snowfall events are done,” said Mike Silva, a Weather Service meteorologist. “You can still get a storm in March or even in April, but once we get through February we’ll be” — he slowed down to choose his words carefully — “all right.”

He sounded almost wistful.

“But once the winter storms are done, then we get our flooding season,” he said, recovering quickly. “It’s always something.”

via One Group Sees Silver Lining in Winter’s Storm Clouds: Meteorologists – NYTimes.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.