Alexandra Bonecutter, a student in the Environmental Studies program with a Marine Science minor, and Ruthann Monsees, a student in the Coastal Environmental Studies program Sustainability Studies program, were part of a SEA Semester voyage that was recently featured in the New York Times (article transcript at the bottom of the page). According to an email distributed by SEA Semester, the voyage “discovered good news regarding coral health in the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) in July, 2016”

The message continues:

PIPA is one of the last remaining coral wildernesses on Earth, about which little is known. An expanse of ocean about the size of California, it is the largest – and deepest – UNESCO World Heritage site.

Accompanied by 21 other undergraduates, SEA Semester faculty, and researchers from the New England Aquarium and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Alexandra and Ruthann gathered data on the health of the islands’ coral reef ecosystem in order to recommend policy implementations to the PIPA management office in Kiribati – all while sailing as active crewmembers aboard our tall ship research vessel!

Ruthann and Alexandra were on voyage class S-268 Protecting the Phoenix Islands. According to Ruthann, “We sailed for six weeks from Honolulu to the American Samoa, focusing on the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA); a Marine Protected Area belonging to Kiribati.” This area, she says, “is recognized as an area with the most “pristine” coral reef system” that “has shown remarkable resilience in the face of climate change, El Nino bleaching events, and anthropogenic effects.”

In 2015, PIPA became a “no-take zone” that prohibits fishing and other consumptive economic uses. Ruthann mentioned that this year was also a large El Nino year. “Our research focused on the policy issues of this area as well as the oceanographic issues: ‘Is 2016 still in an El Nino?’ ‘What are the effects/ recovery of the coral reef?'”

The students had specific projects related to the trip, but in addition to their academics, they appreciated the authentic living and learning experiences at SEA. Ruthann found “the clutter of terrestrial life stripped away” and that she “woke up for her watches with a purpose.” Alexandra saw “the ocean in ways most people have not: exactly how it should be.” It was a “thriving, pulsing with diverse life that is almost as curious about you as you are about them.” Both developed a strong sense of community with their shipmates and highly recommend SEA for the “beauty of sailing, the sense of adventure” and the strong “sense of purpose, growth and opportunity.”

Applicants to SEA Semester must submit undergraduate academic references in order to be accepted into the program, and SoMAS Professor David Taylor reflected on the letter he wrote for Alexandra. He met Alexandra in his Fall 2015 SBC 203 Interpretation and Critical Analysis class, where he discovered Alexandra’s “ability to move easily between the sciences and the arts.” Taylor noted that her “work and writing were exemplary–showing a creativity far beyond her years and an insightful understanding of the need for the sciences and humanities in engaging questions concerning the environment.”

The School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University has a strong relationship with SEA. There are SEA alumni at SoMAS as graduate students and faculty. Students in the Semester by the Sea program at Southampton are eligible for alumni awards that provide financial support for students to participate in the SEA program.

For undergraduates interested in a year-long intensive and immersive experience in coastal AND blue water marine science, a fall semester in the Stony Brook University Semester by the Sea program at Southampton and a spring or summer semester at SEA will provide that experience.

Top Picture: SBU students Alexandra Bonecutter and Ruthann Monsees with some of their shipmates approaching Enderbury Island, the first atoll they visited and their first time sighting land after leaving port in Honolulu.

Below: SBU students Alexandra Bonecutter (top center) and Ruthann Monsees (top left corner) participating in a policy class discussion.

From “Giant Coral Reef in Protected Area Shows New Signs of Life” on the New York Times, 2016-08-16

In 2003, researchers declared Coral Castles dead.

On the floor of a remote island lagoon halfway between Hawaii and Fiji, the giant reef site had been devastated by unusually warm water. Its remains looked like a pile of drab dinner plates tossed into the sea. Research dives in 2009 and 2012 had shown little improvement in the coral colonies.

Then in 2015, a team of marine biologists was stunned and overjoyed to find Coral Castles, genus Acropora, once again teeming with life. But the rebound came with a big question: Could the enormous and presumably still fragile coral survive what would be the hottest year on record?

This month, the Massachusetts-based research team finished a new exploration of the reefs in the secluded Phoenix Islands, a tiny Pacific archipelago, and were thrilled by what they saw. When they splashed out of an inflatable dinghy to examine Coral Castles closely, they were greeted with a vista of bright greens and purples — unmistakable signs of life.

“Everything looked just magnificent,” said Jan Witting, the expedition’s chief scientist and a researcher at Sea Education Association, based in Woods Hole, Mass.

Global climate change is wreaking havoc on corals worldwide. Coral bleaching has caused extensive damage to regions extending from the Great Barrier Reef to the Caribbean and nearly everywhere in between.

“Threats to tropical coral reefs worldwide have escalated to a level that imperils the survival of these complex, diverse and beautiful ecosystems,” Janice M. Lough, an Australian researcher, wrote in a February opinion piece in Nature.

Coral can be severely damaged by rising water temperatures, which cause acidification, as well as by pollution and human activity like tourism, fishing and shipping – prompting some governments to restrict such activities.

If Coral Castles can continue to revive after years of apparent lifelessness, even as water temperatures rise, there might be hope for other reefs with similar damage, said another team member, Randi Rotjan, a research scientist who led and tracked the Phoenix Islands expedition from her base at the New England Aquarium in Boston.

No one actually knows what drives reef resilience or even what a coral reef looks like as it is rebounding. In remote, hard-to-get-to places, our understanding of coral is roughly akin to a doctor’s knowing only what a patient looks like in perfect health and after death, Dr. Rotjan said.

Coral Castles’s revival might be an isolated situation, a fluke in a faraway place. But Dr. Rotjan and her team are on a quest to find out why this coral and other reefs nearby came back to life.

“There’s a recipe book that can be developed out of what we’re learning here,” Dr. Witting said. “You need to make a strong case that this can work before anyone else will try it.”

The lagoon sits in the middle of the largest of the Phoenix Islands, which are inhabited by just a few dozen people, part of the island nation of Kiribati (pronounced KIRA-bas).

The eight-island chain has been listed as a World Heritage Site for its beauty and abundance of wildlife: birds, sea turtles, schools of fish, deepwater sleeper sharks and 200 species of coral. The area has also been a cemetery for sunken ships since voyagers first set out across the Pacific.

To understand the stresses facing corals — from pollution and climate change, for example — researchers would like to isolate each problem. Almost everywhere on Earth, corals must endure climate change and human activity. But not in the 157,626-square-mile Phoenix Islands Protected Area, created by the government in 2008. Shipping lanes skirt the preservation area. Commercial fishing there ceased last year.

Dr. Rotjan, who is also the chief scientist for the area’s conservation trust, said the recent protections might have fostered the coral rebound. The algae that live in corals may also be evolving to cope with warmer temperatures, or hardier coral species may be supplanting others, she said.

In a letter published in Nature earlier this year, another global team of researchers reported a similar coral recovery after they reduced the acidity in three lagoons in the southern Great Barrier Reef, off Queensland, Australia. Carbon emissions increase the acidity of seawater.

“It’s encouraging, because if we do the right things, health might restore in a pretty responsive manner,” said Rebecca Albright, one of the paper’s authors and a postdoctoral scientist at Stanford University.

But few creatures are more vulnerable to ocean acidification from climate change than corals, which have been declining for decades. About a quarter of the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere is absorbed by the world’s oceans, measurably lowering their pH levels, Dr. Albright said.

Forecasters predicted this year would be the warmest on record, driven by the El Niño weather event that started relatively close to the Phoenix Islands. Late last year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declared the third-ever global coral bleaching event, affecting corals in every tropical ocean, and declared that the die-off was being prolonged by El Niño.

The crisis has made the work in the Phoenix Islands even more crucial, said Verena Schoepf, a coral expert at the University of Western Australia. “It’s critical that we understand what happened there, because that would help us understand how corals might be able to cope with climate change in the long run,” she said.

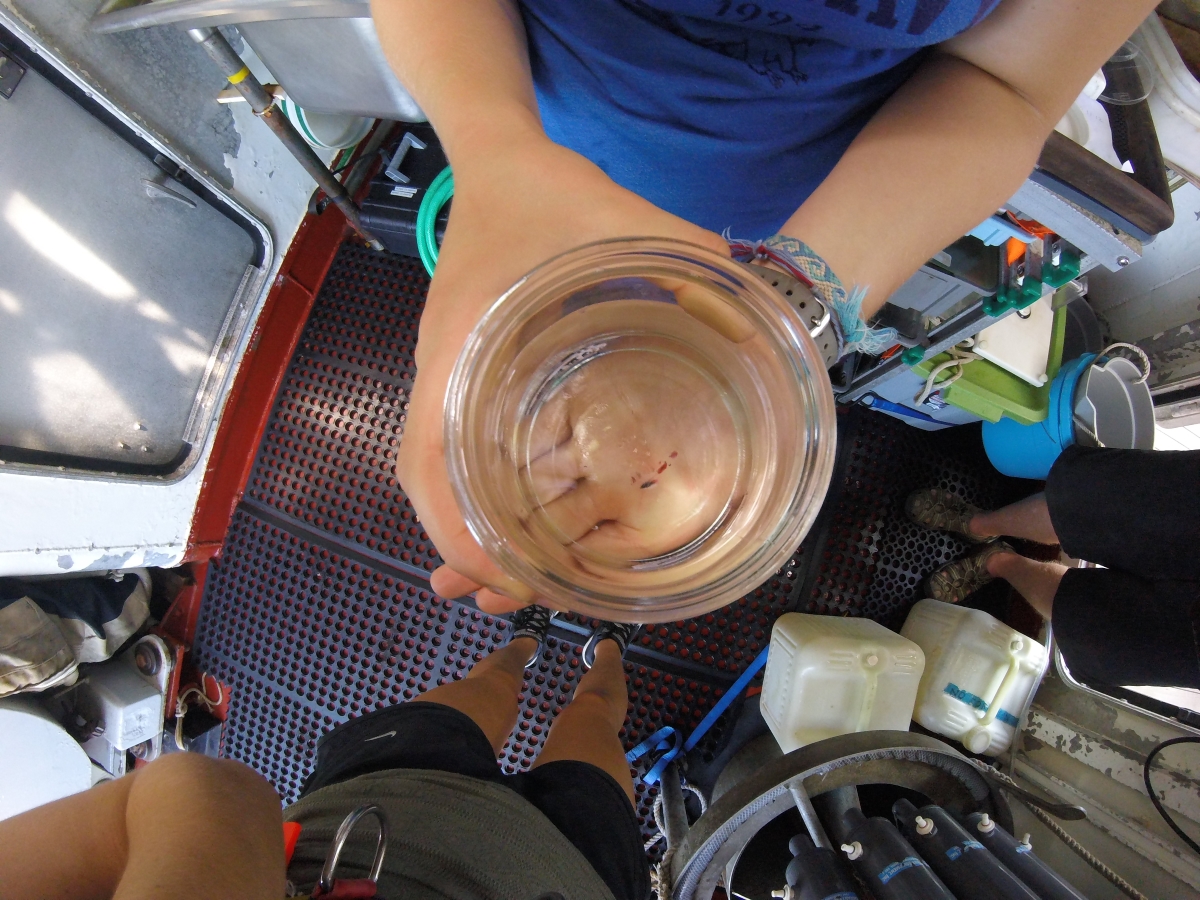

Corals are “animal, vegetable and mineral all rolled into one,” Dr. Rotjan said as she held up displays. The fist-size mineral part, beige with white patches, resembles a featherweight stone full of holes. In a small vial of liquid, she points to the animal part: small beads linked by connective tissue. These living beads act as mouths, drinking in nutrients, and make the calcium carbonate that forms their protective home. The animal shares this structure symbiotically with algae that photosynthesize sunlight, producing food that the animal eats.

Warming water can cause the coral to expel its algae, leading to bleaching. Acidic water weakens a coral’s calcium carbonate skeleton, so it cannot contain the coral and grow. And when the nutrients in the surrounding water change, the coral may have trouble getting food.

Adjusting to climate change, Dr. Rotjan said, is not just about getting used to warmer water. A coral depends on its entire context — its ecosystem, the mineral content of the surrounding water, the sociopolitical climate of nearby human populations. (Reefs off the coast of Somalia, in Africa, may be unusually healthy, for instance, because most boaters have been scared away by pirates, she said.)

Even old shipwrecks make a difference. As the Pacific grows warmer, rusting hulks alongside the Phoenix Islands seem to be releasing more iron oxides. The corals nearest the wrecks are not rebounding as well as those farther away, suggesting that the minerals interfere with coral resilience, according to another member of the team, Sangeeta Mangubhai.

Climate change isn’t just about heating water, Dr. Rotjan said. “It’s about the little sparks along the way that no one is expecting. We flipped the switch, and now we’re watching the fireworks.”

The difference between this year and last is striking, Dr. Witting said. Last fall, in the thick of El Niño, the team’s boat had to use its motor for the whole journey from Hawaii; this year, there has been enough wind for the team to sail.

“Last year, the whole place was holding its breath,” Dr. Witting said. This summer, it has sprung to life with plankton visible everywhere, he said, comparing it to a garden that is six times as productive as usual. “The whole ocean’s in bloom this year.”

The fluctuations of nature are a part of life, of course, and the corals adapt to these variations.

Last year, after visiting Coral Castles, the research team headed to American Samoa to see another giant coral, known as Big Momma, genus Porites, which is among the planet’s largest and oldest, and had been on Dr. Rotjan’s bucket list.

“It is 40 meters in circumference, bigger than the size of this room” she said in a conference room. “She was around pre-Columbus, and now she’s around for the world’s biggest bleaching event.”

It’s still unclear how Big Momma weathered El Niño, which came just a year after another bleaching event.

“Are we the last ones to see her alive and healthy?” Dr. Rotjan asked. “I hope not.”