Montauk Point Blog Entry

by Josh Farber

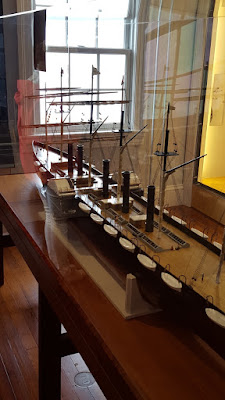

Even the Montauk Point Lighthouse Keepers House couldn’t shield us completely from the winds coming in off the ocean. After collecting ourselves and making sure our hats weren’t blown away, we stepped into the Keepers Bedroom, which contained four models of the Montauk Lighthouse depicting how the lighthouse has changed since its construction in 1796.

The lighthouse was built at a cost of $22,300 from sandstone brought from Connecticut and hauled by oxen. Originally the only structures on the site were the lighthouse and the keepers house, which included a whale oil storage room. 1,800 gallons of whale oil could be stored, providing enough oil for nearly a year of operation. For the keepers of the lighthouse, it was a rather lonely existence. To get to East Hampton took upwards of six hours, if Napeague was even passable.

Our step through history, narrated by Doug Haak, a Montauk Lighthouse docent, continued in 1860. In addition to a garden, an annex was added to the keepers house, providing a place for visitors to stay. 14 feet of height was added to the lighthouse tower for the installation of a Fresnel Lens, which would magnify the light produced so boats could see the lighthouse from a greater distance. The pattern of light was changed to flash once every two minutes.

By 1903 the lighthouse entered a new era. Telegraph signals were erected, a baymark was added to the exterior, and another new Fresnel lens was installed in the tower. This lens, which now lives in the former oil room as a museum artifact, was the light of the lighthouse until 1987 when the lighthouse transitioned to automation.

As Doug continued his narration about the history of the lighthouse during World War II, you could feel the building shake in the fierce winds coming in off the ocean. A surveillance tower was added to the lighthouse property by 1942, and by the 1960s efforts had begun to try and combat the ever-present threat of erosion. Even though we couldn’t go up into the tower, it was still an interesting experience seeing the history of the lighthouse and learning about its significance to Long Island’s East End.

| One of the models of the Montauk Point Lighthouse. This model depicts the elevation of the bluff with exaggerated topography, while also showing the constant erosion eating away at the land. |

My First Time in Montauk

by John Hardie

It was a windy and stormy day, but none of us were discouraged. We set out in the Stony Brook Southampton vans in search for a day of adventure. When we arrived at Montauk, it looked pretty much how I expected it to look. Surprisingly, despite spending the entirety of my life living on Long Island, I had never been to Montauk Point. After exiting the vans and pausing for a few photo ops, I entered the museum, eager to learn everything about the history of this Long Island historic site. We were met by a tour guide who told us about how the lighthouse and the surrounding landscape had changed throughout time. Because Montauk Point is a peninsula, winds come from all directions and erode the land. This is exacerbated by the strong waves that help to erode the beaches. At one point, Montauk was an island separated from Long Island. Due to long shore currents that transport sediment west, the water was filled in and Montauk was connected to Amagansett.

While exploring the museum, I noticed a glass panel on the floor of one of the rooms that was marked “cistern.” Curious, I asked one of the museum guides what it was. She told me that it was used for storing oil, but it was covered up when the coast guard left the lighthouse and discovered accidentally in the late 2000’s by museum staff. The cistern was a large hole in the ground about twelve feet deep. It was lit by an interior light that I couldn’t see, but it casted an eerie glow on the cement hole. The same man who had taught us about the changing landscape of Montauk Point came up to me to offer an anecdote about the cistern. He said that a couple of years ago, a custodian was in the cistern for regular maintenance. Since it was around Halloween time, he left a plastic skeleton down in the cistern. The skeleton wasn’t discovered until two years later by the tour guide himself. Apparently, some garden snakes had found their way into the cistern and were crawling inside of and around the skull of the skeleton. This personal and unpublished anecdote from the museum made me feel as if I had learned some insider information, and I will always remember this and share it with whomever I go to Montauk with next.

After we finished in the museum, we grabbed our lunches and made our way down to Turtle Cove. I saw many fishermen who had been surf casting, but appeared to have had no success. As I bit into my peanut butter and jelly sandwich, I noticed the head of a striped bass laying on the rocks on the beach. A gull picked delicately at the exposed flesh. Intrigued, I began to make my way over towards the fish. The gull backed away tentatively, as I began to examine what was left. I notified Kurt, who picked the head up on a stick to present it to the class. Although most identifying characteristics were gone, the villiform teeth of the striped bass were still intact. After asking some questions about the fish head to the class, Kurt placed it back on the ground, and the gull resumed its meal. It made me happy to see nature come full circle. Some fisherman had caught the fish, beheaded it, and kept the meat to eat or sell. By leaving the head on the beach, he fed some birds and gave a talking point to a college field trip. Nothing is wasted. That’s how life should always be.

Montauk Blog Post

by Michael Cashin

Theodore Roosevelt, Bull Moose of Montauk

by Jay Panko

After our tour of the Montauk Lighthouse Museum, our intrepid group braved gale-force winds for a few moments, congregating again in the fog signal building behind the lighthouse proper. Here, along with learning of the environmental conservation efforts that Montauk is known for, we got a glimpse into the personal history of one of America’s most noted conservationists, Theodore Roosevelt.

This part of the lesson began with a brief history of Montauk’s wartime role. During the time of the Spanish-American War, the greatest threat to life and limb came not from the field of battle, but rather the infirmary. Disease ran rampant, and Montauk itself served as a kind of quarantine location. The distance between Montauk and basically everything else made The End the ideal place for this function. After the war, with so many soldiers having come down with the plethora of diseases they’d encountered in the tropics, Roosevelt and the rest of the returning army spent a month in Montauk, after which Theo was named the Governor of New York.

It turns out, though, his skills weren’t solely in warfare and general survival, but also in diplomacy. Among his many accomplishments, he acted as the neutral mediation between the leaders of Russia and Japan during their time of conflict. He held these mediations not at the White House, but at his home on Long Island, Sagamore Hill. His role was to make the playing field level between both parties… neither one could be led to believe the other was held in higher esteem. He accomplished this in a creative way- he widened the door to his house so that two men could walk in side by side. Typically, the last person through a door in a formal setting is seen as the most important, so when the Russian and Japanese leaders entered the portal into his home, they did so as equals.

The other issue Tara mentioned was that, regardless of the shape of one’s dinner table, someone would end up eating to the right of the host, a spot seen as one of honor. As there were two guests of honor and no other way to make that clear, Theo Roosevelt did away with the idea of a typical, sit-down dinner, and rather led his guests on a walking tour of his home, snacking on hors d’oeuvres. His diplomatic skills were unquestionable, and his role in brokering a peace between Russia and Japan made him the first (of only two) sitting US presidents to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

Fishing.

The End

by Finn Morrissey

This week on the Coastal Cultural Experience field trip, we visited “The End” as its been

tagged. Montauk has been settled since the mid-seventeenth century and is home to the

United States’ fourth oldest and still operational lighthouse which we as a class visited. The

museum holds artifacts regarding the lighthouse itself as well as from the history of the

surrounding area. One side room was home to a small selection of artifacts regarding the

harvesting of the sea, as it were. This includes pieces of fishing, shell fishing, and whaling

equipment. In the fishing section was an array of tackle such as old casting and boat fishing

rods, bate casting reels, harnesses and lures ranging in sizes up to approximately eight inches in

length. Big game fish and commercial stocks were brought in using this equipment, much of

which has stayed relatively the same in style and technique up to the present (Fishing

equipment can be seen in figure one below). The shell fishing gear shown in figure two also has

stayed similar through out the years with a pair of waders and a clam rake on display. Whaling

has long been made illegal in the united states but harpoons and tools for processing were on

display. Today, whales can still be see migrating off the coast of Montauk, and charter boats

such as the Viking fleet run trips specifically to see them.

At lunch, we went down to the shore to eat, relax and take in the salt air. On the beach

countless fishermen suited up in waders, wet suits and enough fishing gear to arm a fleet threw

cast after cast into the turbid waters that make up the end. These fishermen were most likely

attempting to catch bluefish and stripers that had followed the tide in looking for baitfish to

eat. Long Island has an abundance of well managed, offshore and inshore fisheries. Different

locations on the Island have access to different parts of these stocks. Of all the coastal towns,

Montauk has the blue ribbon for being in the midst of the best fishing in New York and with it

comes the largest commercial harbor in the state. Fishermen, such as the ones I viewed, on the

coastal cultural trip, have harvested the water surrounding the light house and the entire point

for generations.

*all photos by Finn Morrissey

|

| Figure one: Fishing equipment on display. |

|

| Figure two: Shell fishing equipment on display. |

|

| Figure 3: Whaling tools on display. |