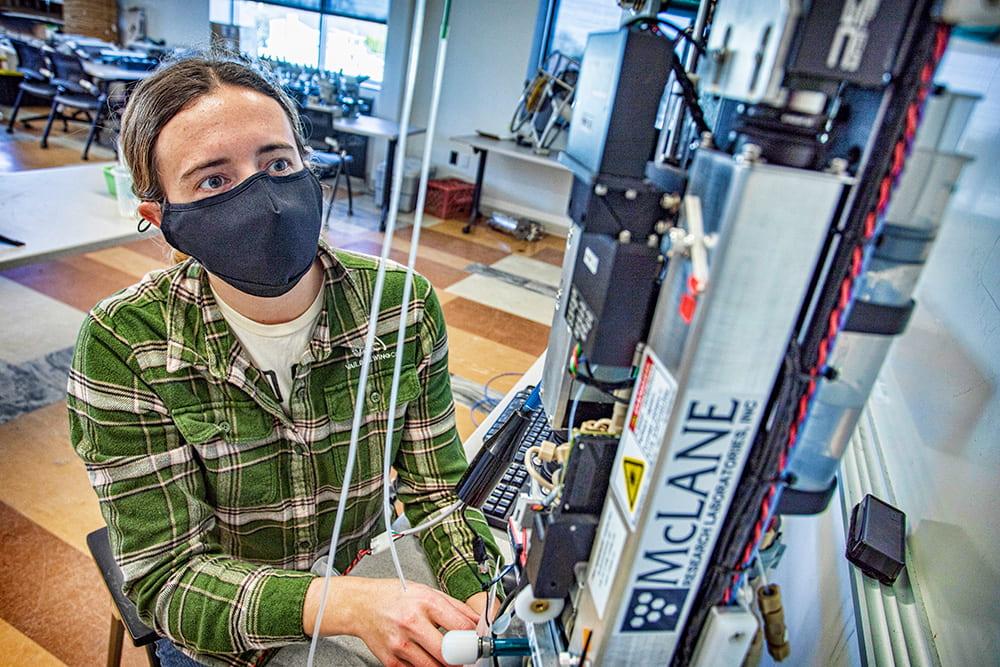

Photo above: Graduate student Rebecca Rogers with the Imaging FlowCytobot (IFCB) at the Marine Sciences Center in Southampton.

From Latest Technology Helping Student Identify Harmful by Glenn Jochum on Stony Brook University News, March 18, 2021

Rebecca Rogers has learned to go with the flow — the Imaging FlowCytobot (IFCB), that is.

The IFCB is a cutting-edge technology used to aid in the research efforts of marine scientists — an automated submersible imaging flow cytometer that generates images of particles in-flow taken from the aquatic environment.

A graduate student in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS), Rogers works with the IFCB, which provides real-time images and identification of all species and, for the purposes of Rogers’ research, HABS, or harmful algal bloom species. The IFCB takes the picture; its operators use the images and computer programs to teach a classifier to identify the images faster than Rogers and others can collect and identify samples.

Built by McLane Research Laboratories, the IFCB can classify images with great specificity — to the genus or even species level with demonstrated accuracy comparable to that of human experts.

“We can collect images from it 24/7 and in some bays where we know the HABs are annual or frequent, the IFCB will allow us to have early detection of low levels of the HAB species that might not be easily detectable in other monitoring,” said Rogers. “But if you can imagine the number of water bodies on Long Island, it is hard to monitor any of them with the frequency that the IFCB can. The IFCB will allow us to look at the water even when we don’t sample for HABs.”

Rogers added that the machine’s cost prevents placing one in every body of water around Long Island. “But with this machine, we can hopefully catch some blooms earlier and start more frequent monitoring in other areas or warn shellfish farmers to take any action needed.”

Rogers explained that researchers sample locations once a week, or they get a sample where the water color has changed, which it does for some HAB species. “So unless you have the people power to keep collecting samples every hour of every day, it can be tough to catch a bloom early sometimes,” Rogers said.

The IFCB takes about a teaspoon every 20 minutes through a syringe and takes pictures of all the plankton with chlorophyll (phytoplankton) within, and uses lasers to distinguish between the chlorophyll and other debris that goes through the syringe. “We can get the pictures off the machine and run them through a program to generate features, ranging from how big it is, how round, to other features that computer scientists have determined are features on phytoplankton and then use image classification to identify the images,” she said.

The IFCB takes about a teaspoon every 20 minutes through a syringe and takes pictures of all the plankton with chlorophyll (phytoplankton) within, and uses lasers to distinguish between the chlorophyll and other debris that goes through the syringe. “We can get the pictures off the machine and run them through a program to generate features, ranging from how big it is, how round, to other features that computer scientists have determined are features on phytoplankton and then use image classification to identify the images,” she said.

There are probably about 100 or so IFCB machines around the world, mostly in the U.S., and Stony Brook has two — one deployed in Old Fort Pond in Southampton and one used in the lab.

Although she grew up in the metro Detroit area, Rogers never questioned that her path would lead her to marine sciences. “My maternal side of the family visited Ocean City, New Jersey every two years, so I got to visit the ocean from 10 months of age on,” Rogers said.

Rogers opted for undergraduate studies at the University of Hawai‘i, where she volunteered with the Hilo Marine Mammal Response Network and the Turtle Response Team, and studied a range of topics from coral reef ecology to tropical wetland ecology.

In her final two years there, she received the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hollings Scholarship, which led to an internship at the Northwestern Fisheries Science Center in Seattle monitoring harmful algal blooms. This led her to compare phytoplankton dynamics at submarine groundwater discharge zones in Kīholo Bay and Hilo Bay for her senior thesis her final year in Hawaii.

“Initially I wanted to study marine megafauna, and it evolved throughout college to oceanography, then algae,” Rogers recalled. “The internship in Seattle really confirmed that for me.”

Rogers’ post undergraduate work was based in the Great Lakes Basin. She first worked as a technician at the Lake Michigan Biological Station focusing on all life stages of yellow perch. She then moved back to Michigan to work with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources investigating movements of the invasive Grass Carp in the western Lake Erie Basin.

Wanting to get back to algae research, Rebecca accepted a graduate position in the Gobler Lab at Stony Brook.

Asked why she chose HABs as her research focus Rogers simply said, “It’s a human, health, economic, and environmental problem that won’t go away without further action and research. HABs combined my research interests with the ability to help people and the environment at the same time.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.