TRIENNIAL REPORT 2018-2020

Making Scientific Research Count at Stony Brook University!

People

Awards and Honors

Each year, SoMAS confers a number of awards on undergraduate and graduate students in recognition of exceptional academic performance, extramural activities, and service to the SoMAS community. Additionally, SoMAS faculty members regularly receive national and international recognition from professional and other societies for their scholarship and/or teaching excellence. Below is a list of awards to SoMAS students and faculty during the report period. Specific information on the student awards can be found on the SoMAS web site.

Faculty and Staff Honors

Chancellor Awards

Excellence in Professional Service

2018 Mark Wiggins

Excellence in Teaching

2018 Sharon Pochron

Excellence in Adjunct Teaching

2019 Maria Brown

Stony Brook Alumni Association Dean’s Choice Award

Justin Bettenhauser

Magdalena Wrobel

Justin Bettenhauser

Bridget Hyland

Magdalena Wrobel

Grace Ahn

Timothy Skula

Katherine McKeown

Skyler Graap

Anna Smith

Austin Reed

Claire Garfield

Courtney Stuart

Laura Osa

Kyle Walter

Sabrina Holsborg

Noor Hamden

Kenny Rothwell

Best Thesis Awards

Joseph Charnawskas, MS

Cheng-Shiuan Lee, PhD

Raymond Sukhdeo, MS

Adam Herrington, PhD

Evan Horowitz, MS

Yang Zhou, PhD

Faculty

Marine Science Faculty

Faculty

Sustainability Studies Faculty

Endowed Professorships

Bassem Allam

Endowed Professor of Marinetics

Marine invertebrate physiology and health, Shellfish Genomics, Aquaculture

Josephine Aller

Professor

Marine benthic ecology, invertebrate zoology,marine microbiology, biogeochemistry

Katherine Aubrecht

Division Head, Sustainability Studies / Associate Professor / Faculty Director, Coastal Environmental Studies

Phone: 631-632-5360

Fax: 631-632-5375

chemical education, sustainable and green chemistry

Steven Beaupré

Associate Professor

Marine Biogeochemistry, Chemical kinetics of natural organic matter, radiocarbon analyses

David Black

Associate Professor

Paleoclimatology, paleoceanography, deep-sea sediments, marine micropaleontology

Henry Bokuniewicz

Distinguished Service Professor

Near shore transport processes, coastal groundwater hydrology, coastal sedimentation, marine geophysics

Malcolm Bowman

Distinguished Service Professor

Coastal ocean and estuarine dynamics

Bruce Brownawell

Associate Professor

Biogeochemistry of organic pollutants in seawater and groundwater.

Kurt Bretsch

Lecturer / Faculty Director, Semester by the Sea

Marine and Environmental Science Education, Coastal Community Ecology

Arlene Kons Cassidy

Lecturer / Faculty Director, Sustainability Studies

Robert Cerrato

Professor

Benthic ecology, population and community dynamics.

J. Kirk Cochran

Distinguished Professor Emeritus

Marine geo-chemistry, use of radionuclides as geochemical tracers; diagenesis of marine sediments.

Brian Colle

Professor / Director, ITPA

Extreme weather, coastal meteorology, weather forecasting, regional climate change

Jackie Collier

Associate Professor

Phytoplankton physiological ecology; Biocomplexity and microbial diversity; Planktonic ecosystem processes in marine, estuarine, and freshwater systems

Ali Farhadzadeh

Assistant Professor

Nearshore hydrodynamics, sediment transport, wave-current-sediment-structure interaction, resilient coastal protection systems, coastal flooding

Donovan Finn

Assistant Professor / Faculty Director, Environmental Design, Policy, and Planning

community-based planning, disaster recovery, resilience policy, urban design and placemaking

Nicholas Fisher

Distinguished Professor / Director, CIDER

Marine phytoplankton physiology and ecology, biogeo-chemistry of metals, marine pollution

Michael French

Associate Professor

supercell and tornado dynamics; Doppler weather radar applications; mesoscale meteorology

Christopher Gobler

Endowed Chair

Coastal ecosystem ecology, climate change, harmful algal blooms, phytoplankton, ocean acidification, effects of multiple stressors on coastal marine resources, aquatic biogeochemistry

Sara Hamideh

Assistant Professor

Endeavour Hall 167a

disaster recovery and community resilience

Sung-Gheel (Gil) Jang

Assistant Professor / Faculty Director, Geospatial Center

Geospatial Sciences and geographic information systems

Marat Khairoutdinov

Professor

Climate modeling, high-resolution cloud modeling, cloud microphysics, super-parameterization, massively parallel super-computing, cloud parameterization

Hyemi Kim

Associate Professor

low frequency climate variability, tropical meteorology, ocean-atmosphere interaction, prediction and predictability, tropical cyclone activity, extreme events

Daniel Knopf

Professor

Atmospheric Chemistry, Microphysics and Chemistry of Atmospheric Aerosols, Heterogeneous Atmospheric Chemistry and Kinetics

Pavlos Kollias

Professor

Cloud Microphysics and Dynamics, Environmental Remote Sensing, Radar Meteorology and Technology

Ping Liu

Research Associate Professor

Climate change, dynamics and modeling;

Darcy Lonsdale

Professor

Ecology and physiology of marine zooplankton; food web dynamics of estuarine plankton and the impacts of harmful algal blooms.

Glenn Lopez

Professor Emeritus

Marine benthic ecology, animal-sediment interactions

Kamazima Lwiza

Associate Professor

Structure and dynamics of shelf-seas and remote sensing oceanography

John Mak

Professor

Trace gas isotopic composition for the reconstruction of atmospheric chemistry in the paleo atmosphere; trace gas emissions from the biosphere; development of instrumentation platforms for research aircraft.

Anne McElroy

Professor

Aquatic Toxicology

Emmanuelle Pales-Espinosa

Research Associate Professor

Shellfish physiology, Particle selection mechanisms in suspension-feeding bivalves, Algology

Sharon Pochron

Lecturer / Faculty Director, Ecosystems and Human Impact

ecotoxicology and soil ecology

Roy Price

Research Assistant Professor

Hydrothermal vents, water-rock reactions, toxic metal & metalloid cycling in coastal environments, arsenic bioaccumulation, vent-biota relationships, and alkaline shallow-sea vents

Kevin Reed

Associate Professor

Climate Modeling; Climate Change Attribution, Tropical Cyclones; Climate Extremes; Atmospheric Dynamics, Science Policy

Tara Rider

Lecturer

Maritime and Environmental History, Sustainability

Carl Safina

Endowed Chair

Ocean animals, fisheries, human relationship with nature

David Taylor

Assistant Professor / Faculty Director, EHM

environmental humanities, history of naturalist studies, American Literature, nature writing

Gordon Taylor

Professor

Marine microbiology, interests in microbial ecology, trophodynamics, anoxia, hypoxia, single-cell analysis, Raman microspectrometry and atomic force microscopy

Lesley Thorne

Assistant Professor

Bio-physical and trophic interactions in marine ecology; application of spatial analysis and landscape ecology techniques to marine conservation

Nils Volkenborn

Associate Professor

Sediment biogeochemistry, animal-sediment interactions, benthic ecology

Joe Warren

Associate Professor

Acoustical oceanography, Zooplankton behavior and ecology

Laura Wehrmann

Assistant Professor

Marine Biogeochemistry, Geochemical element cycles, Deep Biosphere

Robert Wilson

Associate Professor Emeritus

Estuarine and coastal ocean dynamics

Christopher Wolfe

Associate Professor

Physical oceanography, large-scale circulation: theory and modeling.

Karina Yager

Assistant Professor

Climate change impacts; Remote Sensing; Land-cover and Land-Use Change; Alpine Ecosystems; Andes; Mountain Societies, and Sustainability Studies

Minghua Zhang

Professor

Climate modelling, atmospheric dynamics

Qingzhi Zhu

Associate Professor

Chem-/Bio- Sensors, Marine Biogeochemistry, Trace Elements, Environmental Analytical Chemistry

Carl Safina Endowed Research Chair for Nature and Humanity

Carl Safina is the inaugural recipient of the Carl Safina Endowed Research Chair for Nature and Humanity in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences.

Carl Safina is an international leader in ocean conservation and is the first endowed chair in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences. Through Carl Safina’s work, the Safina Center aims to help people understand how the ocean supports all life on our planet. This is a rare opportunity for the campus to celebrate academic and research excellence.

Endowed Chair of Coastal Ecology and Conservation

The Endowed Chair of Coastal Ecology and Conservation was made possible by the generous support of four long term and dedicated donors committed to the research conducted by Chris Gobler.

Marinetics Endowed Professorship in Marine Science

The Marinetics Endowed Professorship in Marine Science was made possible by the generous and gratifying support of a donor. It is conferred to a SoMAS full-time faculty who conducts world-class research in one or more of the following areas: population biology of fisheries, fishery ecology, marine ecology, aquaculture, marine animals, marine animal health, marine habitat health, and closely related areas in marine science.

Bassem Allam has been selected as the first Marinetics Endowed Professor in Marine Sciences. This tremendous honor recognizes the quality, productivity, and importance of Professor Allam’s research. An investiture ceremony will be organized by the university to celebrate the conferral of the professorship. You will be invited to the event at that time.

Endowed Professorship of Ocean Conservation Science

Ellen Pikitch is the inagural holder of the Endowed Professorship of Ocean Conservation Science. This endowed professorship is funded by the Ocean Sanctuary Alliance and an anonymous private donor both committed to the research of Ellen Pikitch.

Stephen Baines

Associate Professor

Jeffrey Levinton

Distinguished Professor

Heather Lynch

Assistant Professor

Dianna Padilla

Professor

Adjunct Faculty

James Ammerman

Adjunct Professor

Aquatic microbial ecology and biogeochemistry; estuarine, coastal, and open ocean phosphorus cycling; coastal eutrophication and hypoxia; molecular biology of microbial phosphorus assimilation; instrument development and automation; academic leadership and administration; research administration.

Michael Cahill

Adjunct Professor

Application and development of environmental law in local government

Nolwenn Dheilly

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Evolution of Host-Parasite Interactions

Anthony Dvarskas

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Environmental economics, ecosystem services and resilience of coastal ecosystems, economics of restoration, natural capital accounting

Mark Fast

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Aquatic diseases and Immunology

Charles Flagg

Research Professor

Continental Shelf Dynamics, Bio-Physical Interactions in Shelf Systems, Climate Change Effects on Coastal Systems, Shipboard ADCPs on Volunteer Observing Ships

Huan Feng

Adjunct Professor

source, transport and fate of contaminants in estuarine and coastal systems

Roxanne Karimi

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Dana Hall 167 Ecological stoichiometry of metals, aquatic environmental health, and physiological ecology.

paul.kemp@hawaii.edu

Growth and activity of marine microbes in water column and sediment; benthic-pelagic interactions; molecular ecology of marine bacteria

Karine Kleinhaus

Research Associate Professor

Wuyin Lin

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Ph.D., 2002, Stony Brook University Climate Modeling, Climate Change.

Yangang Liu

Adjunct Professor

Physical, optical and chemical properties of atmospheric particles, including aerosols, clouds and precipitation

Stephan Munch

Adjunct Associate Professor

Evolutionary ecology of growth and life history traits, Evolution in harvested populations, Applied population dynamics modeling, Mathematical modeling and statistics

Joyce Novak

Adjunct Assistant Professor

management and sustainability, marine spatial planning, coastal and wetland ecology

Janet Nye

Adjunct Associate Professor

Fish ecology, climate variability, global environmental change, ecosystem-based management, ocean acidification, climate change

Christine O'Connell

Adjunct Professor

connections between science and society, with a focus on marine spatial planning, ecosystem-based management, waste management, conservation planning, and ecosystem services.

Roy Price

Research Assistant Professor

Hydrothermal vents, water-rock reactions, toxic metal & metalloid cycling in coastal environments, arsenic bioaccumulation, vent-biota relationships, and alkaline shallow-sea vents

Nicole Riemer

Adjunct Assistant Professor

The interaction of atmospheric transport processes with chemistry and microphysics, particularly for trace gases and aerosol particles in the troposphere

Keith Roberts

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Unstructured mesh generation for geophysical problems; parallel computing; numerical analysis; coastal ocean modeling.

Frank Roethel

Adjunct Professor

Discovery Hall 131 Ph.D., 1982, State University of New York at Stony Brook Environmental chemistry, Municipal solid waste management impact

Stephen Schwartz

Adjunct Professor

Earth energy budget and climate change; Budget and lifetime of anthropogenic CO2; Role of tropospheric aerosols as shortwave forcing agents; Atmospheric radiation; Cloud chemistry and acid deposition.

Matthew Sclafani

Adjunct Assistant Professor

horseshoe crab ecology

Andrew Vogelmann

Adjunct Professor

Atmospheric radiative transfer, cloud and aerosol climate interactions, climate and the Earth’s energy balance, remote sensing, cloud and climate modeling

Sandra Yuter

Adjunct Professor

Adjunct Lecturers

Mirza Beg

Adjunct Lecturer

Maria Brown

Lecturer

M.S., Long Island University

Adam Charboneau

Adjunct Lecturer

Kimberly Durham

Adjunct Lecturer

Scott Gianelli

Adjunct Lecturer

James Gilmore

Adjunct Lecturer

Fisheries Management, marine law and policy.

Arthur Kopelman

Adjunct Lecturer

Jeong-A Seong

Adjunct Lecturer

Jeffrey Tongue

Adjunct Lecturer

Michael White

Adjunct Lecturer

Roger Flood

Jim Quigley

Robert Wilson

Glenn Lopez

John Graham

Paulette Gerber

David Hirschberg

Andrew Brosnan

Retirements

As representatives of the public for the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS), members of the Dean’s Council are the primary external force moving the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences to the realization of its opportunities for mission fulfillment and service to its constituencies. Working with the Dean and his designated representatives, the Dean’s Council provides advice and guidance in the areas of planning, advancement, organization, and operations. The current Dean’s council members are:

| Sarah Chasis | Senior Attorney and Director, Oceans Program, Natural Resources Defense Council | |

| Rosalind Walrath | Board, New York League of Conservation Voters. | |

| Michael Halpern | President, East Hampton Beach Preservation Society | |

| Laurie J. Landeau, VMD | Associate Director, Aquavet; Marinetics, Inc. and Co-founder, Marinetics | |

| Robert J. Maze, Ph. D. | Co-founder and Vice President of Marinetics, Inc. | |

| Jane Ross | Vice President, Alfred and Jane Ross Foundation, Inc. | |

| Dieter von Lehsten | Co-chair, Town of Southampton Sustainability Advisory Committee | |

| Danny Lu, Ph. D. ’96 | CEO and co-founder of Seawolf Technologies, Inc. | |

| Michael White | Environmental Law Practice | |

| Michael J. Zeitlin | CEO, Aqumin LLC | |

| Ex Officio: | ||

| Paul Shepson, Ph. D. | Dean, School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences | |

| Deborah Lowen-Klein | Assistant Vice President for Advancement, Stony Brook University |

Alumni

One of SoMAS’s paramount objectives is to educate and train students to become the next generation of marine and atmospheric scientists, environmental resource managers, and citizens who possess a fundamental grasp of environmental issues and the choices that society faces in handling these issues. The alumni of our undergraduate and graduate education programs thus represent perhaps most important of the School’s “products,” extending the influence and impact of SoMAS on the broader society of which it is a part. Of all the things we produce, our alumni are inarguably the most valuable and have the most impact on the issues and problems that command the School’s attention. SoMAS alums occupy a dizzying variety of positions within academia, natural resource management agencies at all levels, and in the offices of non-governmental organizations. Alumni are often in a position to play a critical role in support of various SoMAS research and educational efforts. Several SoMAS alumni are represented on the Dean’s Council, a small assembly of influential individuals who advise the Dean on overall program development priorities and help to get initiatives underway. Several years ago, SoMAS began a concerted effort to strengthen connections with its alumni. Working with the Stony Brook University Alumni Association, our alumni records have been consolidated so that our communications with alumni are more comprehensive, reliable and, ultimately, effective.

MSRC/SoMAS produced its first masters degree graduates in 1971 and, a decade later, its first Ph.D. recipients. Through the years, 911 students have joined the ranks of SoMAS alumni, 266 with the Ph.D. and 715 with a masters degree, and 72 students received both degrees. As of December 2019, a total of 611 students have graduated with an undergraduate degree from SoMAS. Of these, 264 received the Environmental Studies degree, 59 the Atmospheric Sciences degree, 120 the Marine Sciences degree and 168 the Marine Vertebrate biology degree.

To each of our alumni, there is a story. Alumni below were highlighted between 2018 and 2020.

Wayne Penello ’79 Talks Risk Management

From Wayne Penello ’79 Talks Risk Management on Stony Brook Matters, by Kristen Brennan, on November 18, 2020.

Wayne Penello ’79 is not afraid to take risks. In fact, he’s built a career out of it.

As president and founder of Risked Revenue Energy Associates, Penello helps companies understand the importance of risk management. Now, he’s sharing his 40 years of experience in Risk is an Asset — a book he penned alongside his colleague Andrew Furman that has been published by Forbes Books.

But Penello wasn’t always in risk management. With a master’s degree in Marine Sciences from Stony Brook University, he began his career as a research scientist. Somewhat unexpectedly, Penello told us, it’s his research training and his experience at Stony Brook — that led to his success in business. Penello even dedicated his book to his professors at Stony Brook, acknowledging their role in his career.

Tell us more about your journey from Stony Brook University to your role as president of Risked Revenue Energy Associates and now author?

As a businessperson specializing in commodity price risk management, I’ve had the privilege of working on a vast range of complex problems. The education I received at SBU helped me develop a foundation of skills that eventually led to my understanding of statistics and chaotic systems.

My late advisor, Bud Brinkhuis, was a researcher and professor who made every effort to broaden my analytical and communication skills. His influence and support gave me the confidence to approach and obtain the training I needed from several other excellent scientists, both on campus and elsewhere. As a graduate student, I conducted experiments and studied at Cornell’s Veterinary College, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Brookhaven National Laboratory and Stony Brook’s medical school. I also was part of a research team of marine scientists that took samples across the Caribbean Sea. Bud was my advocate through everything. The breadth of experiences offered by Bud and the other scientists and the access each of them afforded to me played an important role in opening my eyes to my own potential and accelerating my growth.

It sounds like your experience as a student had a profound impact on your career. Can you tell us more about that?

While I was a student, something magical happened. I took a statistics course that was then called Biometry, which introduced me to Analysis of Variance. At the time, it was a relatively new statistical tool and had only just become popular because computing costs had come way down. This course was my epiphany. I loved the course.

Back then, most students would sit for hours at the Computer Center punching cards that would program the computer to solve their homework problems. My challenge was that the Marine Science Research Center was on the South Campus, and the Computer Center was on the Main Campus. The bus ride between the two could easily take 45 minutes each way. I needed a more efficient way to get my work done.

Using my Texas Instrument TI-100, a hand-held calculator with 99 programmable steps, I broke the programs for each statistical test into a series of subroutines, each small enough to fit on the calculator. This allowed me to solve these problems in my South Campus office, saving me a lot of time. More importantly, by delving deeply into the math for analysis of variances, I developed an appreciation for the logic behind the tool. I was so excited about my new knowledge that even before the course was over, I started looking for ways to apply my new skills everywhere. I was fortunate to publish research papers with several scientists and professors who used these tools to further their research. These collaborations gave me the confidence to look beyond the opportunities at Marine Sciences.

What inspired you to take the leap and write Risk is an Asset?

I want businesses subject to commodity price risk to become resilient by maintaining appropriate levels of protection. When a company fails, it affects many people. Investors lose money, but employees lose their jobs and sometimes their retirement savings. My hope is that if managers have a better understanding of their risk, they will appreciate the benefits of process risk management and adopt it. Rather than focusing on math, my book explains its application and the utility of risking budgetary performance estimates. I wrote the book in a way that makes it approachable for students, in the hope that they will read and learn from it. These students will be the next generation of business leaders; hopefully, this book will help them prepare for many challenges.

With your degree in marine sciences, you began your career as a research scientist. How does this factor into the work you do today?

One of the great dangers in today’s world is that disinformation is continually being circulated and re-circulated. One publisher will print a knowingly false statement, only to retract it the next day. Unfortunately, before that happens, other news publishers will regurgitate that information as if it were true. This creates a long trail of referenced information that is wrong. Today, we must all challenge and check facts. My training as a research scientist helped me develop into a critical thinker and prepared me for today’s challenge of sifting through multiple and independent sources of information to find the data I can trust.

What advice would you give to students looking to follow in your footsteps?

If you’d like to make a lot of money, solve BIG problems. The bigger the problems you solve, the more likely you are to get paid well. But you also need to be good at solving these problems, so pick something that interests you. I have been fortunate to have loved going to work every day of my life. That allowed me to live a life filled with passion. If you can, make your avocation your vocation. Then you will love your work and have a good chance to become great at it. If there is someone out there who is doing the things you are interested in and good at it, go work for them. Surround yourself with excellence if you want to become an expert. As they say here in Texas, the fruit never falls far from the tree.

So, what’s next for you?

My current focus is to develop a suite of tools that individual investors can use to manage their investments more wisely. The challenge is to make these simple enough for everyone to use yet powerful enough to give them confidence that they will be better off if they proactively manage their investment portfolios.

SoMAS Alum Celebrates Release of First Book

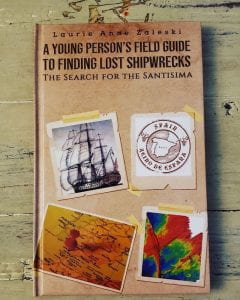

Laurie Zaleski has found a way to communicate her science to new audiences and published her first book. A graduate from the lab of Dr. Roger Flood, she earned her M.S. degree from the Marine Sciences Research Center (now SoMAS) at Stony Brook University in 2002.

A Young Person’s Field Guide to Finding Lost Shipwrecks is Laurie’s autobiographical account of an actual nautical archaeological expedition. The book is written from the surveyor’s point of view and explains the math and science behind multibeam sonars and how to use the technology to find shipwreck. Along the way she describes the equipment used to explore the seafloor. The reader is taken through a typical day at sea on a marine research vessel equipped with a multibeam sonar and ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle) on a real-life expedition in search of a shipwreck. The story begins alongside a dock in Cadiz, Spain with a team that includes Laurie, three archaeologists, two college students on a summer internship, three captains, one cook, one engineer, two SCUBA divers and one able-bodied seaman onboard the Hercules, a 37 meter research vessel and are in the midst of getting ready to set sail in search of the Santisima.

Readers will learn a lot more than science in this true-life account of a scientific expedition. They will learn history, eat tapas, and dance the flamenco all while in search of a 300-year-old shipwreck. Introducing Multibeam and Acoustic Reflectivity to children – What could be better? And women scientists! Yeah!

She says she wrote A Young Person’s Field Guide to Finding Lost Shipwrecks “because of my love of science,” and “moreover my love of my 12-year-old granddaughter and the essential need for all children, especially girls, to keep their sense of adventure firmly intact as well as to find a connection to themselves through math and science.”

Thanks to her time at SoMAS launching her into her career, Laurie has been fortunate to have travelled the world–from the Arctic Circle to Saipan and all points in between conducting geophysical surveys. She has mapped thousands of kilometers by plane, boat and foot. She fondly remembers her time at Stony Brook as a turning point in her life. She had donated a copy of the book to SoMAS as a way to inspire the next generation of brilliant young oceanographers!

Thanks to her time at SoMAS launching her into her career, Laurie has been fortunate to have travelled the world–from the Arctic Circle to Saipan and all points in between conducting geophysical surveys. She has mapped thousands of kilometers by plane, boat and foot. She fondly remembers her time at Stony Brook as a turning point in her life. She had donated a copy of the book to SoMAS as a way to inspire the next generation of brilliant young oceanographers!

The book is available on Amazon in Kindle and Hardcover.

Zaleski, L.A. (2020). A Young Person’s Field Guide to Finding Lost Shipwrecks: The Search for the Santisima. Austin Macauley Publishers.

SoMAS MCP Program Prepares Grad for Influencer Role

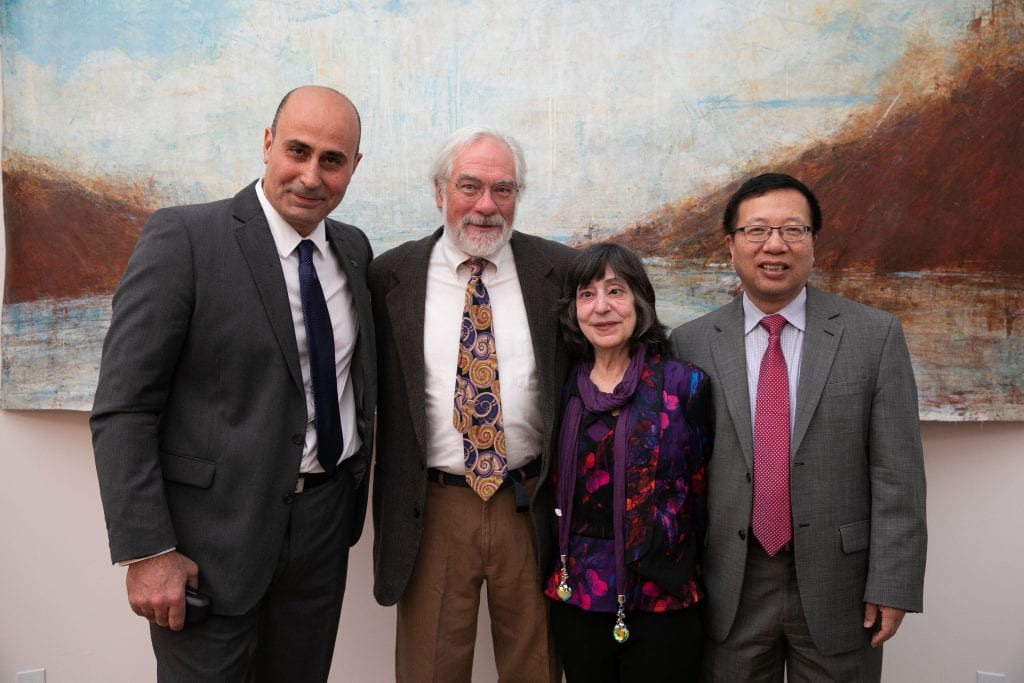

Photo above: Alan Alda, center, with Rachael Coccia, left, and her graduate advisor Kate Fullam.

From Master’s Program Prepares Grad for Influencer Role by Glenn Jochum on Stony Brook University News, May 27, 2020.

Helping to clear our shores of unsightly and dangerous plastics is both a mission and a great job for Rachael Coccia ’17, who earned a master’s degree in the Marine Conservation and Policy (MCP) program at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS).

“I was looking for a unique program that would allow me to specialize in communicating about marine conservation topics to bridge the gap among scientists, policymakers and the public,” Coccia said. “The one-year program offered that flexibility.”

Coccia, a resident of San Diego, California, described her time at Stony Brook as “pivotal,” helping her get to where she is today: plastic pollution manager at the Surfrider Foundation, a nonprofit environmental organization that works to protect the world’s oceans and beaches.

In her position, Coccia directs the nationwide Ocean Friendly Restaurants and Beach Cleanup programs from the foundation’s headquarters in San Clemente, California.

Coccia credits her time working as a graduate assistant at the University’s Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science for the development of important skills that she would use in her career.

While there she managed The Flame Challenge, an international competition that challenges scientists to explain complex science concepts in ways that are understandable to an 11-year-old. In that role, she reviewed hundreds of entries from scientists explaining energy to kids.

“Having the chance to work alongside Alan Alda was incredible,” said Coccia. “He’s very involved with the Center and in particular, The Flame Challenge.”

She also enjoyed several courses offered at the Alda Center, including Improv for Scientists.

“This class was very eye-opening as I watched scientists from many different disciplines come together to explore their science and learn techniques to better communicate about what they do,” she said.

Another highlight: taking a video production class at the Alda Center in which she documented a trawl survey and developed a video featuring the work of the Shinnecock Bay Restoration Program.

“We pulled up some incredible specimens, including some adorable puffer fish,” she said.

Coccia’s knowledge of things pelagic came easily to her, even though she grew up in landlocked Rochester, New York. That’s because she was always enamored of the outdoors, spending hours running through the woods and playing in a creek. Later on, she became a lifeguard and competed on her high school’s swim team, earning her the nickname “Fish.”

Her most cherished outings, however, were to the beaches of the East Coast. “I would play in the water for hours on end, search for critters under the rocks and dive down to the ocean floor to enjoy the relative peace beneath the waves,” she recalled.

It was through the MCP program that Coccia connected with the Eastern Long Island chapter of Surfrider.

“That introduced me to the Ocean Friendly Restaurants program,” she said. “I was able to visit restaurants to discuss the program with them, learn of the obstacles they would face and come up with solutions.”

That experience proved vital to her current role as the program’s national director.

The path to Surfrider was a circuitous one, but a bit of luck mixed with persistence landed her a dream job.

Coccia first applied for the position of plastic pollution manager soon after graduating from Stony Brook. She made it to the final round in the interview process but ultimately did not get the job because there were more qualified applicants, she was told.

“It’s a very competitive field to find jobs in because these are the jobs that will ultimately save our planet,” Coccia explained.

So she interviewed for a number of related positions online before changing her approach and getting the experience she needed.

Her new strategy was to set up face-to-face chats with local organizations, which led to her taking a part-time position with The Ocean Project, the global coordinator for World Oceans Day. A full-time position became available in 2018.

As the director of youth initiatives overseeing the World Oceans Day Youth Advisory Council, Coccia was able to work remotely before moving across the country to San Diego. Nearly a year after she moved, she saw another posting for the plastic pollution manager position at Surfrider. She interviewed for it this time in person — and landed the job.

Before she enrolled at Stony Brook, Coccia earned a bachelor’s degree in public relations at Fredonia State University, and hosted an associate-produced 40 episodes of the Aqua Kids TV Series, an Emmy award-winning K–12 program that educates young people about ecology, wildlife, science and how it relates to them.

That experience reinforced her commitment to communicating about the crisis caused by plastic pollution — and the outrage she felt learning about the mistreatment of the ocean. The images of marine life tangled in plastic seared into her brain during an undergraduate environmental science class.

Today, she consults with the inaugural Surfrider Club Leadership Council to encourage more involvement and integration with its 100-plus student clubs across the nation.

“The solutions already exist — it’s just a matter of scaling them up and implementing them on a larger scale,” Coccia said.

She said there are approximately 630 Ocean Friendly Restaurants across the country that have committed to using reusables only for on-site dining, avoiding plastic bags and straws, and instituting other plastic-free policies.

Coccia said some people avoid single-use plastics by arming themselves with reusable alternatives, from cups and bags to straws and containers. For those looking to remove all single-use plastics from their lives, there are DIY hackathons that offer instruction on how to make soap, toothpaste, cleaners and more in reusable containers.

“The problem is that it shouldn’t be up to individuals. The plastics industry and larger corporations that profit from plastic put us in this mess, and they should be held responsible to help us out,” Coccia said. “When we can hold them accountable through policies like extended producer responsibility, that’s when we’ll truly be able to leave our toxic addiction to plastic in the past.”

#SeawolvesForLife

Greg Marshall (PhD, 2019)

From For Greg Marshall ’88, an Emmy-Winning Career Started at SoMAS on Stony Brook News on May 30, 2019

Imagine being underwater and seeing a shark swimming nearby.

What would go through your mind? Fear? Wonder?

When Greg Marshall ’88 saw a shark in the water near him off the coast of Belize in 1986 — while doing research for his master’s in Marine Science at Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (SoMAS) – he was struck by inspiration. That inspiration would lead to a career with National Geographic, two Emmy Awards, and, at Stony Brook’s 2019 Commencement, an honorary degree.

The inventor of the Crittercam, a non-invasive camera that allows researchers to record animal behavior in the wild, Marshall was presented with an honorary Doctor of Science at the Doctoral Hooding ceremony on May 23. Prior to the ceremony, he discussed Stony Brook’s influence on his career, his work with National Geographic, and his experience returning to campus as the Akira Okubo Visiting Scholar in 2017.

What does it mean to come back to Stony Brook to get an honorary degree?

As you can imagine, it’s amazing. I’m completely thrilled, and a bit overwhelmed. It’s such an incredible honor, and I suppose I think of it as the cherry on top of having an interesting career that started here 30 years or so ago. I didn’t go the academic route and pursue a PhD, but the fact that it’s come back to this is really a wonderful culmination of 30 years of hard work and a pretty fulfilling life.

Are you going to insist that anyone call you “Doctor?”

Of course! I’ve got my kids calling me “Doctor” already!

Actually, I’m a pretty casual guy, so I’m not going to insist on anything, but it would be a very nice little treat.

You mentioned that your career started here. Take us back 30 years or so. What brought you here?

I’d finished my undergraduate degree in 1981 at Georgetown, and I had thought I’d go to law school. I was prepared to go to law school — I was interested in international law — but I thought I’d take a couple of years to explore other things as well. I was interested in photography and journalism, so I moved to New York City and explored photojournalism. At the end of a year and a half, I decided, “Well, this probably isn’t for me, and I’m still not that interested in law school” — my dad’s a lawyer, so law school had always been part of the equation. But, I just wasn’t passionate about it, so I made a list of things that I was passionate about. No matter how I parsed that list, marine biology was on top. I thought, “I’m 28 years old. I’m young. Why not give it a shot?” So, I decided to find the closest marine science program that had a good reputation, and Stony Brook was at the top of that list. I came out the next day to talk to people, and brought my academic records with me. What I heard was, “You know, you’re well prepared for law school, but you’re not ready for marine science. You’ve got a lot of work to do to get into this graduate program.” They outlined what I needed to do: physics, chemistry, calculus, and all these things that I hadn’t focused on in college. I was told, “If you can do this, and do it well, then we’ll consider you.” The following year I spent here at Stony Brook doing those core undergraduate courses. When I finished I came back to the Marine Sciences dean and said, “Well, we talked a year ago, here’s my transcript for the things you told me I needed to do. Now, what do you say?” He looked at it, and said, “I told you this is what you needed to do, and you’ve done it, so welcome aboard.”

This was my passion, as it had been since I was a kid. It’s great that my brother came for the Doctoral Hooding ceremony, because it was really he and I together, out exploring in the ocean, snorkeling together, diving together that really nurtured the passion I have for the ocean. So, finally I was here, pursuing something that truly inspired me, and I remember this incredible feeling of satisfaction and completeness. I remember walking back from class one day feeling “This is where I should be. This is right.” It was a really fulfilling, complete feeling. As it turns out, the rest of my career happened by good fortune and some, of course, preparation to be lucky. I was fortunate to have learned some of the skills and background I needed to ultimately have a life changing encounter with a shark which opened my eyes to new research possibilities.

Let’s talk about the shark.

I was a student here, pursuing my master’s degree, but doing my actual physical research in Belize. I was diving for the research, and out there one day and had an encounter with a shark. I’d had others, but this one was a unique experience for two reasons. First, I’d just built an underwater camera for a film I’d decided to make about the research I was doing and the problem that I was trying to solve (at the time I was dealing with the demise of the queen conch populations in the Caribbean as a result of overfishing — and I made the film from the locals’ perspective about their overfishing of this critical resource). I didn’t have any money, so I had to build my own underwater camera which enabled me to make the film which generated money for marine conservation in Belize. So, the whole concept of filmmaking and conservation came together at that point in my history. So, I’d just built an underwater camera system, and it occurred to me the moment I saw a remora, a suckerfish, suckled onto the belly of the shark, “The camera that I’ve just built is about the same size as that remora, and if I streamline my camera, I wonder if we could ride along with the shark. The shark might not change its behavior, because it’s used to having a remora ride with it. We could learn amazing new things about sharks’ behavior and ecology.” That was the moment that my life changed course again. That was the start of the Crittercam. I thought, “Surely, someone’s done this,” but discovered that no one had, and I became passionate about trying to make it happen.

I came back to wrap up my degree here, write my papers, submit my thesis, and while doing that, I decided to see if National Geographic would be interested in my idea. I called them up, and they agreed to have me come by and talk. Well, they were gracious, saying “Yeah, interesting idea, but we don’t fund ideas that are quite this new and untested.” So, it took another five years of really intensive work on my own, with some little grants here and there — including one from Stony Brook — before I got my first grant from National Geographic in 1991. The next year, I secured another grant from Geographic, and they said, “This is interesting; you’re proving this thing.” Following that I starting contracting with them then joined the staff a year or so later. I was staff for the next 23 years in various capacities: I was a scientist/specialist, then executive producer, and ultimately vice president.

What was the first footage that you got that made you say, “Wow, I’ve really got something here?”

The very first footage was from that captive animal in Belize, a sea turtle. What was interesting about that was that the turtle behaved normally, and all the other animals in the pen with it behaved normally. It gave me confidence that this system had potential, because the animal itself didn’t behave differently, and the other animals it was interacting with didn’t behave differently, so it gave me the sense that there was real potential for doing good science.

Then in 1992 or 93, National Geographic decided to make a film about me and my early efforts, and they captured the moment on film of us seeing the first images from a wild, free-ranging animal in its natural habitat — a tiger shark. That moment was just spectacular. It was years of commitment, belief, and rejection and work, wrapped up in a moment where we finally see the world from from a wild, free-ranging animal perspective and I realize this is going to work. It was extraordinary.

If you go to drama school, you may think that maybe, one day, you’ll win an Emmy. You go to film school, maybe you think about winning an Emmy. You go to school for marine science, you don’t think about winning Emmy Awards. What did it mean for you to win those two Emmys?

It’s fun, obviously. You stand up there, they call your name, and you think, “Really?” There’s that moment, which is incredible.

In terms of the meaning, it’s bit more complicated. The award itself is fantastic. That part of it, to be recognized, contributing something unique and new in the film world, is terrific. I love it. But it became a bit of a professional challenge because the images are captivating and people in the media world began to think of this as media and not science. They would say, “These are cool images, and we should get more cool images for film.” Problem is, my primary objective is science and research.

I began to get calls from producers saying, “We’ve got to put cameras on the back of X, Y, and Z,” and I said, “Well, we could, but we’re working with animals and will only do so if there’s a good scientific rationale for it.” If we get great images that can be used in films and stories, fabulous, but our primary objective will always be science and research, and if that’s not the primary objective, I’m not interested.

Media and its impact in conservation are critical. My concern was the potential harassment of animals strictly for media ends, and that’s something I decided not to allow to happen. If it’s for research, and if interaction with animals is necessary in order to do the research, that’s a risk worth taking. Simply put, when we’re interacting with animals, there must be a level of additional ethical responsibility.

You came back to Stony Brook a couple of years ago as a visiting scholar. What are your perceptions of SoMAS today compared to what you saw as a student?

You guys have grown incredibly. The whole department (and university) is so much more diverse and robust than when I was here. That’s not to say that it wasn’t at that time; after all, the Marine Science program was considered one of the best coastal oceanography programs in the country. It’s been terrific to see the growth, the further investment, and the dedication to the fundamental principles of conservation and sustainability. It’s exciting, and important, and I’m thrilled to be a part of it.

Chris Crosby (BS, 2019)

From Chris Crosby ‘19 Aims to Leave the Planet Healthier Than He Found It on Stony Brook News by Glenn Jochum

Maybe it was going hunting and fishing with his grandmother. Or being glued to the Discovery Channel as a kid. Either way, Chris Crosby’s love of nature was too strong to ignore, and led him to enroll at Stony Brook University following a tour of duty with the United States Army.

Crosby ‘19 went to college right out of high school, but soon realized he was there for the wrong reasons.

“I mostly went because all of my friends were going and I didn’t know what else to do,” said the Oakham, Massachusetts native.

After nine months working in the family business, a machine shop, he joined the Army.

“I was trained as an interrogator and sent to Hawaii, where there was no one to interrogate,” said Crosby. That led to him performing an array of random jobs ranging from occasional Humvee mechanic to shelter construction to map builder.

Off-duty he tried his hand at SCUBA instead, which rekindled his passion for the natural world. At the end of his tour of duty in the Army, Crosby realized that he was ready to return to academia so he focused on searching for schools with reputable marine biology programs. Since he was also looking to head back home to the Northeastern U.S., Stony Brook proved to be a perfect fit.

After two semesters of basic biology he was ready to make the plunge into the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook (SoMAS) core classes and focus entirely on marine life as a student in the Marine Vertebrate Biology program.

He cites Conservation Biology, taught by Liliana Davalos, as one of his favorite classes as Professor Davalos challenged the class to figure out on its own the issues that face the living world we inhabit and devise solutions.

Chris also credits Conservation of Seabirds, taught by Emily Runnells and Marine Ecology, taught by Jeff Levinton for helping shape his academic interests, specifically mentioning Runnells’ use of academic papers from students to guide her lectures and Levinton’s use of humor and anecdote to unearth “gold mines of information.”

In the summer of 2018, Crosby interned at Volunteers for Wildlife, Inc., in Locust Valley, New York, caring for and treating injured and orphaned wild animals native to Long Island, helping them prepare for eventual release into their natural ecosystems.

“Skills I got to hone or learn while at Stony Brook are too lengthy to list,” said Crosby. “Some great educators aided me in the never-ending quest to polish up my writing. I learned more about statistics than I ever thought possible.” And in the ESHOP, the Instrument lab at SoMAS, Tom Wilson and Alex Sneddon have each taken me under their wings to instill a bit of know-how when it comes to their areas of expertise — Alex in meteorological instruments and fieldwork — and Tom in oceanographic equipment and engineering.”

Chris worked on an ESHOP invention, the Vortex Debubbler, which uses centrifugal force and gravity to extract bubbles in sea water flowing to high precision ship’s instrumentation, greatly increasing data accuracy. During his three years working at the ESHOP, SoMAS has sold 75 debubblers to institutions worldwide – a sizable fraction of about 229 units supplied since Tom Wilson and former ESHOP colleague Henry Harrison invented the debubbler in 1987.

This is where working at his father’s machine shop training came in handy. Chris has also worked on setting up and installing atmosphere radars for SoMAS that have found their way from the Hamptons to New York City buildings. And most recently, he has worked on SoMAS’s new Slocum Glider, an unmanned submersible that will take autonomous readings of the waters off the southern coast of Long Islands for weeks at a time.

By summer’s end, Chris will head to the Department of Ecology and Evolution at Rutgers University and begin pursuing his PhD, to study how foxes and other scavengers that adapt well to human environments are affecting the coastal ecosystems of New Jersey. His eventual dream is to work in wildlife management or conservation biology.

“I don’t care whether I work at an academic institution, for the government, or for a private organization,” he said. “I just want my work to have a positive impact on the world so that I can leave the planet a little healthier than I found it.”

Savannah LaBua (BS, 2016)

From Record-Tying 11 Stony Brook Students Win Prestigious NSF-GRFP Fellowships on Stony Brook News, April 19, 2019.

In a record-tying performance, 11 Stony Brook University students – including nine women – have been awarded prestigious Graduate Research Fellowships (NSF GRFP) by the National Science Foundation. Another six SBU students earned Honorable Mentions. Among those students was Savannah LaBua, a graduate of the Marine Vertebrate Biology program at SoMAS.

Currently working at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), LaBua studies Pacific herring, a critical component of the eastern Gulf of Alaska ecosystem, providing a viable food source for humpback whales, sea lions, seabirds, other fish, etc. Stocks have experienced significant declines in abundance since the development of industrial fishing. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game has closed fishing for eight of the ten stocks managed in Southeast Alaska but most have failed to recover since the 1980’s. Data and knowledge gained from this study would be of great interest in marine ecology because it directly addresses questions of what factors maintain and distribute variability in marine populations and the importance of their influence.

Savannah plans to “start graduate school this Fall at Florida International University under the supervision of Dr. Kevin Boswell.” She met Dr. Boswell through her participation in the National Student Exchange program at Stony Brook University. Savannah credits her participation in the program for providing “me with an opportunity to build my scientific network, acquire new skills and expand my ecological toolbox.” She studied for two semesters at Florida International University under the supervision of Dr. Kevin Boswell, “where we implemented active acoustics and remote sensing technology to examine biological interactions across a variety of habitats.” The research she conducted as an undergraduate reflected well in her NSF GRFP application.

The NSF GRFP was established in 1952 to help develop and boost diversity of the country’s science and engineering research workforce by supporting graduate students who pursue research-based master’s and doctoral degrees in NSF-support STEM disciplines.

“This award is crucial to promoting social mobility for our most promising STEM students and to providing them with the freedom to develop their own research agendas,” said Jen Green, External Scholarships and Fellowships Advisor. “I was humbled by the talent and hustle displayed by this cohort and am thrilled by the university community’s celebration of their accomplishments in this year’s NSF GRFP competition.”

Students interested in the NSF GRFP and other fellowships, should visit the Office of External Scholarships and Fellowship Advising for more information.

You must be logged in to post a comment.