By Megan Mahoney ~

I just wanted to get away. After a year of discussions, I persuaded my father—who had been living in the United States as long as I could remember—to let me come live with him in los Estados Unidos. With his agreement, I thought my fight for a new future was over. Little did I know it was just the beginning of a much greater battle: the battle of bureaucracy.

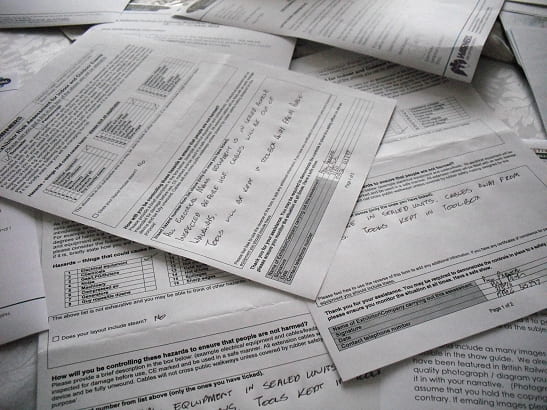

There is no way to say it gently: Immigration sucks. I felt overwhelmed by the mass of paperwork. I spent the next year shuffling back and forth between my island home and the mainland.I visited the consulate, embassy, and hospital for all the necessary examinations and each time, somehow, something was wrong with my application. “REJECTED” was printed across the top in bold, red-stamped lettering. I felt exhausted and disillusioned. Would I ever even get to America?

April 24, 2010. This is a date I will never forget. It was a Saturday, and not just any Saturday: It was my first day in the United States. Although I had been to the United States a few times before for vacation and holidays, I had never traveled here alone as I did that day.

At the airport checkpoint, the immigration official cleared my passport and handed me a yellow folder. Receiving that magical yellow folder made it so real for me in that moment. After so many applications being returned for something being off—stamped with “REJECTED. REJECTED. REJECTED”—I could not believe there were no more “buts.” Realizing my paperwork had been actually approved and nothing needed to be altered or resubmitted filled me with excitement. I was an American and this was my new life!

While my dad worked, I would walk the busy streets and admire the omnipresent signs directing me through my mostly Spanish-speaking neighborhood. In Venezuela, there had been no signs. I was fascinated with them and tried to distinguish their meanings. “STOP” one boomed on a red octagon. I observed cars and other pedestrians and slowly began to learn the meaning of this sign and the many others that lined my neighborhood.

Fortunately, my dad’s connections within the community helped me to find a job within my first two weeks. A Dominican woman hired me to work “under-the-table,” which meant I was working secretly and would be paid in cash.

Being so rapidly thrown into life in America made me nervous. I didn’t know how to take the bus. I didn’t know how to speak English. I had taken English in high school, but how many American recent high school graduates can move to Spain and be immediately proficient in Spanish? Nadie. My saving grace was my Dominican boss’s bilingualism.

“Every American dream has to start somewhere,” I thought to myself as I boldly picked up a ringing phone, not knowing if I would understand what I would hear on the other end.

Once I received my my social security card and the other vital documents that made me “legal,” I immediately enrolled in ESL classes at Nassau Community College. English did not come easily to me, but I took pride in the small steps and felt as though I was finally gaining some independence in my new American life.

From there, I was able to apply to college and was accepted right away. Like my initial immigration, this period of my life came with multitudes of paperwork: I had to get a driver’s license, register for medical insurance, and submit all my supporting documents to finalize my acceptance to Nassau Community College as a matriculated student. Studying in English was a daunting possibility, but I nonetheless pursued Media and Communications for I’d never lost my passion for the subject.

As I began my studies, I anticipated poor treatment from my peers, but my experience was completely different from what I had expected. The other students were kind and accepting, helping me with my English. They found it so cool that I had just moved here from Venezuela and taught me a lot about American culture. We spent afternoons after class chatting about our favorite foods and television shows. They invited me to join them for meals and asked how I was handling school. My classmates were very patient with me, even through my thick, impossible-to-understand, accent.

Unlike the students, however, some teachers and staff at Nassau Community College delivered racist and condescending treatment. I had expected the adult professors to be more understanding and supportive of me than the students had been, but this was so not the case. They made me feel subordinate and treated me unequally. I had never felt stupid before in my life, but some of my professors beat down the self-confidence I had had in Venezuela.

I was picked on in class by my professors and blatantly laughed at, to my face, by staff for not being able to correctly pronounce the word “chalk.” One man even once called his coworker over to join in making fun of me. I felt like I was being put on display.

“Come see this hilarious girl who can’t speak English!”

I will never forget that moment. I always had a lot of confidence in myself, but to come here and be treated so inferiorly was horrible. Although I was cursed with these discriminatory faculty members, I was, fortunately, blessed with other lovely professors who enriched and improved my experience.

With time, my English improved, and I decided to pursue a communications degree. I recognized that I could not have possibly chosen a more frustrating major for someone newly learning a language, but it was my dream and I refused to give it up.

My first major classes at Nassau Community College were extremely challenging. In Venezuela, speaking Spanish, I had always excelled at getting my message out. In the United States speaking English, however, I felt quite the opposite. I felt mute. I would try to speak and I would not know the exact word to use, so I would use a similar one,r but it would never transmit quite the same meaning. It was extremely frustrating, and sometimes I would cry, but I tried to be patient. Gradually, my English continued to improve and I lost the shyness that my language barrier had given me.

Against all odds, I persevered and graduated from Nassau Community College, applied to Stony Brook University, and was accepted as a journalism major.

I am now a senior and am preparing to graduate in May. I have now been in the United States for six years and still struggle with the language but my English has improved greatly.

I am very proud of myself for not giving up on my dream. I hope with time I will be able to broadcast in New York—in English—with the same precision, charisma, and confidence that I have in Spanish. But, most importantly, today I feel like myself again—the self I had been in Venezuela.