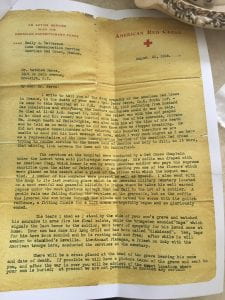

Letter from Emily Patterson to the family of Matthew Serra. Photographs provided by Anthony Amorello

By Anthony Amorello

Originally written for HIS 301 with Professor Jared Farmer

Over a hundred-and-one years ago, my ancestors received the news that every military family dreads- the news that on August 19th, 1918, my Great-Great-Uncle Peter was killed in the Great War. “I write to tell you of the deepest sympathy of the American Red Cross in France over the death of your son, Cpl. Peter J Serra…” I can only imagine how they must have felt upon seeing that letter from the American Red Cross. Unadulterated sorrow and grief surely accompanied it. One can only imagine what it’s like for a family to lose a child, and though the pain they must have felt was surely unimaginable, there was one comforting aspect. The letter they received had delivered the heartbreaking news in a manner that was heartfelt and kind. It is an extremely emotional letter and that is deeply important to my family. Even I, who didn’t know anything about this ancestor, was almost brought to tears upon my first time reading it. It’s contents feel personal and heartfelt, which made it an exception in my mind. Many similar letters that I’ve found were merely fill in the blanks with lines for the dead soldier’s name, place and manner of death, etc. In the course of my research, I found out the letter was not so exceptional. More on that later. While this letter is a direct product of the Great War in all of its horror, it is also a beautiful document. The author was clearly influenced by various aspects of their reality: the horrors of modern war to be found in World War I, the high level of religiosity in the west, the fact that the writer was an American, the fact that the writer was a woman, and that the writer was a member of the Home Communications Service, among other things.

In order to analyze any primary source it is first important to understand its author. The person who wrote to my family was a woman named Emily A. Patterson. Though she didn’t leave much of a record behind, there are a few things that can be discerned about her. For one, she was a woman, a factor that likely did play a part in the exceptional nature of the letter. Another is that she addresses herself as part of the Red Cross Home Communications service, which specializes in sending news of soldiers, be it that they’re ill, wounded, or deceased in my ancestor’s case, to their families.[1] It’s also discernible that she was an American citizen, by virtue of the fact that she was a member of the American Red Cross. She was also presumably Christian, based on the fact that she was alive during a period of religious fervor in America. It is even more likely she was Catholic. The fact that she was possibly a Catholic is apparent in some of the language she uses in the letter in regards to the significance of rosary beads, a Catholic symbol.[2] All of this information, though minimal in quantity , is very important to understanding why the letter is the way it is, as will be demonstrated later.

Just as it is significant to have some information about the author of the letter, it is equally important to have some information on the subject of the letter. Corporal Peter Serra, my great-great-uncle, was the firstborn son of two Italian immigrants to the United States, Matteo and Maria Serra. Born in Brooklyn in 1895, he was raised as a first generation Italian-American in a heavily Catholic, and therefore alien, tradition. Though a sect of Christianity, Catholicism was heavily stigmatized in Protestant America during this time period and associated with unwanted immigrants from Ireland and Italy. Peter Serra was the oldest of four brothers and one of them, Marco, fathered my grandmother. Peter Serra was 22 when he was drafted in September of 1917. He served with Company K. of the 308th Infantry Regiment – 77th Division, one of the first to see active service in France.[3] Not much is known in my family about his personal life, because after he died he became a sensitive subject to discuss in my family. To get an idea of just how painful a topic he was, it’s worth noting that after his death, his mother only wore black for the rest of her life. The family stopped talking about him all together after his parents were gone too.[4] There’s really only one thing about his personality that is discernible from the letter. Namely, Peter Serra took his religion with a certain level of seriousness, as he brought his rosary beads with him to the front lines.[5] Much like Ms. Patterson, not much is known about Peter Serra. While this lack of information is unfortunate, it still gives a glimpse into the life and personality of Corporal Serra.

Another important factor that went into this letter was religion. While still important to many today, religion played a vital role in most people’s lives in 1918. This led many Americans to see the war through a religious lens. Edwin Ebel, a writer on religion in the Great War, recounts an American volunteer in the Canadian Army, saying“‘…defend the principles of humanity and chivalry which the Creator has handed down.’”[6] Ebel also states that there was a widespread attitude at the time that “the fate of Christian humanity… in the balance.” [7] The idea of the Great War as moral via religious beliefs and values are represented many times. For one, Patterson describes Serra’s sacrifice as “…the ultimate sacrifice upon the altar of patriotism.”[8] Here she invokes religious language and imagery, that of an altar and sacrifice, two religious motifs, as well as a fundamental value of the time, patriotism. Patterson also links religion and the military when she describes “Yes, Taps [a military funeral song] for him have been sounded, and he is resting calm and free; after while he will awaken to stand God’s Reville [a song played to rouse soldiers from sleep]”[9] Religion’s influence on the letter is also present in the way Patterson makes specific mention of the fact that, “…the priest was with him and prayed with him as he died, and his rosary was buried with him.”[10] She also makes sure to mention that, “Lieutenant Flanagan, a priest on duty with the American troops here, conducted the services at the cemetery.”[11] To a secular person, these things would mean rather little; one is still dead whether or not the religious rituals are carried out. However, to a family of religious Catholics like the Serras were and continue to be, the knowledge that their son’s final spiritual needs were tended to must have been a great comfort. This was surely something Patterson knew, or else she would have not mentioned it. Through those elements of the letter, it’s clear that the religiosity of the times played a role in how the letter was written.

Another factor that influenced the letter is the fact that Patterson was an American. For instance, a lot of the language that Patterson used to console the Serra family invokes contemporary American symbols, beliefs, and values. For one, Patterson makes sure to emphasize the fact that Serra’s coffin was, “…draped with an American flag…”[12] In the same sentence, she links the Stars and Stripes with an American value, an honor, “…won by every American soldier who pays the supreme sacrifice upon the altar of patriotism.”[13] Another way that Patterson’s citizenship affected the letter is that she uses language that makes war out to be glorious and honorable. This was a common notion amongst the major warring powers before and early on in the war. Political Scientist John Mueller recounts,“…before the First World War, it is easy to find serious writers, analysts, all over Europe and the United States who hail war, ‘not only as an unpleasant necessity… but as spiritual salvation and hope of regeneration.’ After the war, such people (e.g. Benito Mussolini) became extremely rare.”[14] The brutal, bloody, futile nature of the First World War did a lot to kill this perspective in most parts of the Western World. By 1918 war started to be seen in the west as, “…repulsive, uncivilized, immoral, and futile.”[15] However, in August 1918 the United States had only had troops in combat for a few months, so such ideas remained prevalent. Patterson showed how affected she was by these ideas about war in several parts of the letter. For one, in a way that evokes the old world ideals of war as a gallant enterprise, she describes Serra’s life as, “…one so gloriously ended.”[16] He died from Mustard Gas inhalation, something very few would call glorious today. She described his epitaph, namely that he was killed in action, as, “the most glorious epitaph that can befall a soldier.”[17] She then describes the war he died in as, “…a great cause…”[18] Now one might not disagree with these statements about sacrifice and the Great War, which is very understandable, but that doesn’t change the fact that at this point in the war those attitudes of the greatness and nobility of war definitely shifted in most of the warring powers barring America.

A significant detail in regards to the nature of the letter is that Emily A. Patterson was a woman. This is important for a few reasons. To begin, some of the language that Patterson uses would not befit the gender expectations of men at the time. For example, Patterson notes that she wept at Serra’s funeral. “The tears I shed as I stood by the side of your son’s grave and watched his comrades in arms fire the final salute, while the trumpeter sounded ‘Taps,’ which signals the last honor to a soldier, were tears of sympathy for his loved ones at home.”[19] Though not unheard of, men at the time were, and in some places still are, expected to be stoic and less emotional, particularly in regards to crying. Therefore, while a man would certainly still try to comfort the bereaved, he would likely not reference the fact that he cried for the sake of his masculinity. Another aspect of gender at the time that is reflected in the letter is the widespread belief among women in the contemporary warring nations that serving in the Red Cross or, other volunteer organizations, to help the war effort was merely their way of doing their part for their countries and their soldiers in the monumental undertaking of the First World War. In fact, many war nurses’, “…motives for nursing the wounded had more to do with their desire to be part of ‘great struggle of war’ than any wish to develop their skills as nurses.”[20] While Patterson’s patriotism has already been discussed at length, and while she wasn’t a nurse performing operations, it’s important to note that she uses language that reflects certain aspects of the aforementioned sentiment. She states her task as, “…trying to render service to the brave Sons of America…”[21] She emphasizes that she is doing a service to her country and to people and families of the nation. In other words, like the many other women who served in the Great War, doing her part for her country. Patterson’s femininity certainly played a role in some of the letter’s language.

Another contributing factor to the letter’s nature is that Patterson was part of the Home Communications Service and not an actual field nurse for the Red Cross. The fact that those two functions were separate kept Patterson away, to a degree, from the intense suffering and death witnessed by field nurses. While she still did work in a field hospital, she was spared the trauma of performing field operations.[22] The level of carnage and bloodshed that Red Cross nurses had to witness was intense, no matter their country of origin, and many became disillusioned rather quickly. According to one wartime nurse, Shirley Millard, an American serving in a French hospital, at the beginning of the war she pictured that she would be, “gliding silently among hospital cots, placing a cool hand on fevered brows, lifting bound heads to moisten pain parched lips with water.” [23] Instead, what Millard actually found in service was,

“gashes from bayonets. Flesh torn by shrapnel. Faces half shot away. Eyes seared by gas; one here with no eyes at all. I can see down into the back of his head. Here is a boy with a grey, set face. He is hanging on … too far gone to make a sound. His stomach is blown wide open, and only held together by a few bands of sopping gauze which I must pull away. I do so, as gently as I can. The odour is sickening; the gauze is greenish yellow. Gangrene. He was wounded days ago and has been waiting in the grounds. He will die …”[24]

It’s all but impossible to not find oneself discouraged and even mentally scarred by what wartime nurses saw and experienced. The level of idealism and elegance of the language used in the letter would not have been possible from someone who had to perform on brutally scarred and/or painfully dying men. That’s why the Home Communications Service existed in the first place, and necessarily part of the reason the letter is so evocative. Patterson’s lack of hands-on experience with handling the wounded and dying was without a doubt a contributing factor to why the letter is the way it is.

The letter itself is also a reflection of the brutal nature of the First World War. It was the first real modern war. Death was found and carried out in a myriad of new and brutal ways, ways that American troops simply had no experience with. The 308th Infantry of the 77th Division (Peter Serra’s regiment and Division) first engagement showed the plucky boys from New York what modern war was, and it is a good example of the worst fighting of the war. Alan Gaff, writer on the 77th Division as well as other topics, recounts:

“All hell broke loose at 3 a.m. on June 24. High explosive shells, alternating with phosgene and mustard gas… some three thousand rounds slammed into positions occupied by the 307th and 308th Regiments… the German’s swarmed forward, firing machine guns and throwing grenades, while overhead aircraft either strafed American positions or bombed them. Liquid fire from flamethrowers was shot through the grey, smoke filled dawn… Flood [a Lieutenant of the 308th] described the ensuing brawl as ‘a hand-to-hand fight— kicking, biting, stabbing, scratching, anything to get the other fellow first…’[25]

While wars tend to stay the same fundamentally, the scale of carnage and destruction of World War I was unprecedented. It was in the monumental and horrific tragedy of the First World War that the paths of Patterson and Serra crossed, even if it was only briefly, and only after Serra was already gone.

Clearly these horrors would have to have some effect on the contents of the letter. The first and most obvious impact is the cause of death stated in the letter, namely Mustard Gas poisoning.[26] The Great War was one of the first times in human history during which American troops have been killed in large numbers by chemical weapons. The second thing is that while the letter is certainly well written and contains personal and heartfelt components, the sad truth is the majority of the letter originates from a template. Due to her position, Emily A Patterson had to write a lot of letters like the one my family received. Based on a letter written by Patterson to the family of a soldier named W. J. Tigan, it is clear that certain portions of both his and my ancestor’s letters are exactly the same[27]. They are still her words, and those words still evoke emotion, but large sections of the letter are indeed copy-paste. However, one cannot blame Patterson. The fact that these letters are strikingly similar is in of itself a product of the Great War because of the mass scale of death and carnage that the war wrought. Conditions at the front while both men were there, specifically in August, were horrendous. Richard Slotkin, another author on the exploits of the 77th Division, recounts:

“They [elements of the 306th and 308th Regiments] suffered intense artillery bombardments… gas claimed the largest share of victims [like Peter Serra]… the air was full of the stench of the unburied dead… Each of the frequent bombardments they suffered renewed the stench, churning the old dead out of the ground and creating new dead. They saw dead men and men killed and wounded every day…”[28]

Shortly after, the 77th Division lost 4,700 men in just one broad offensive action, nearly 17 percent of its initial strength[29]. Patterson surely would have had to write hundreds of letters in August alone. Writing so many letters about the final moments of soldiers, who all surely died in a myriad of gruesome fashions, certainly must have been taxing. It must not have only been hard for Patterson because of the grating nature of the knowledge that so many people had died, but also because coming up with hundreds of heartfelt and comforting things to say in these letters would have been impossible. This said, the fact that Patterson’s letters had any personalization in them, and that the template is still beautiful, should say something about Patterson as a human being and her fitness for such a position in the Home Communications Service. She gracefully and wholeheartedly fulfilled her duty to the best of her ability despite the immense numbers of dead. Her words would have eased the suffering of many, even if it was only a little bit. They serve as a light in the darkness that was World War I, even if its brutality and scale left their marks on the letters.

Though the letter isn’t quite as personal or exceptional as one would think at first glance, it is still a kind gesture and one that still evokes sentiment in readers even today. All of the aforementioned factors- religion, Americanism, the fact that Patterson was in the Home Communications Service, and the brutality of the war, left their marks on the letter. It is not only an example of the zeitgeist of the First World War, but also of one of the few pillars of goodness and humanity that came out of the war. Despite the new industrial scale of death, governments, organizations like the Red Cross, and the people who served in them, like Emily A. Patterson, all recognized that the mourning process had not joined industry in leaving the home. These groups and people went out of their way to set up and staff services that would, in Patterson’s words, “fill… that missing link between the home and the battlefield,” in a way that would console the millions of families across the globe who were mourning the deaths of their sons, fathers, uncles, and brothers.[30] Though letters can only do so much to ease the pain of someone in mourning, the acts of kindness represented in the writing of their words represent some of the best of humanity’s potential for kindness and empathy, which naturally must comfort one in such suffering, even if it’s only a little.

Endnotes

[1] The American Red Cross, Annual Report – The American National Red Cross, (N/A: American Red Cross. 1919), 96.

[2] Emily Patterson to Matthew Serra, August 22, 1918

[3] Alan Gaff, Blood In The Argonne: The “Lost Battalion” Of World War I. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2005,) 70-71.

[4] Mary Calabrese, interview by Anthony Amorello, November 21, 2019.

[5] Emily Patterson to Matthew Serra, August 22, 1918

[6] Jonathan H Ebel, Faith In The Fight: Religion And The American Soldier In The Great War. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014,) 28.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Emily Patterson to Matthew Serra, August 22, 1918

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] John Mueller, “Changing Attitudes towards War: The Impact of the First World War.” British Journal of Political Science 21, no. 1, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991,) 1-2.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Emily Patterson to Matthew Serra, August 22, 1918

[17] Ibid

[18] Ibid

[19]Emily Patterson to Matthew Serra, August 22, 1918

[20] Christine E Hallet. Nurse Writers Of The Great War. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017,) 172.

[21] Emily Patterson to Matthew Serra, August 22, 1918

[22] Ibid.

[23] Shirley Millard, I Saw Them Die: Diary And Recollections Of Shirley Millard (Los Angeles: Harcourt, Brace, 1936,) 12-13.

[24] Shirley Millard, I Saw Them Die: Diary And Recollections Of Shirley Millard (Los Angeles: Harcourt, Brace, 1936,) 23-24.

[25] Alan Gaff, Blood In The Argonne: The “Lost Battalion” Of World War I. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2005,) 74-75.

[26] Emily Patterson to Matthew Serra, August 22, 1918

[27] Emily Patterson to Matthew Serra, August 22, 1918 + Emily Patterson to Mrs Tigan August 1, 1918, In McClure’s Magazine, compiled by Stella Burke May. New York: S. S. McClure, Limited, 1922.

[28] Richard Slotkin. Lost Battalions: The Great War And The Crisis Of American Nationality, (New York: Macmillan. 2005,) 196.

[29] Richard Slotkin. Lost Battalions: The Great War And The Crisis Of American Nationality, (New York: Macmillan. 2005,) 211.

[30] Emily Patterson to Matthew Serra, August 22, 1918