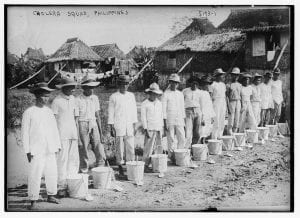

Image of Cholera Squad in the Philippines. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

By Jan Jandayran

On January 27, 1902, a banca[1]arrived at Tobagan, Cebu, from Carigara, Leyte, carrying a corpse. The driver requested to dock his vessel and bury the body, but port authorities denied him entry as they suspected that his passenger had been infected by cholera. Undaunted, the banca driver traveled 29 kilometers(18 miles) south to Catmon, where he was able to land and bury the body. A few days later, several people in the vicinity died from vomiting and diarrhea, the tell-tale symptoms of cholera. This event would not be reported until July,[2] but by then, it would be too late.

This event would be one of the potential origins of a catastrophic epidemic that would leave two hundred thousand dead in the span of two years. Cholera had ravaged the Philippines since the 1860s, but the 1902 Cholera Epidemic was a special case.[3] During this time, the United States was fighting an active insurrection in the Philippines following its annexation in 1898. The official start date for the epidemic was in March of 1902, several months before the insurrection was over. However, the American officials in the Philippines did not take notice of cholera until July of 1902. Due to the interconnected nature of the epidemic and the war, along with the late response by the United States, previous studies of the Philippines within the first half of 1902 focused on the war and regarded the cholera epidemic as the result of an environment left behind by it. Cholera was nevertheless present during the final days of the conflict, so how did the Philippine-American War influence the 1902 Cholera Epidemic? The anti-guerilla policies that the United States implemented and the Filipinos’ apprehension of American epidemic policies hastened cholera’s spread. While the efficiency of the United States in its cholera response was debatable, the 1902 Cholera Epidemic should not be understood as the result of war, but rather as an active combatant that took advantage of the chaos during and beyond the Philippine-American War.

In July of 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt declared that hostilities between the Americans and the Filipinos were over, ending three years of the bloody subjugation of the Philippines.[4] The Philippine-American War, also known as the Philippine Insurrection, stemmed from the unwillingness of the imperialist United States to grant Filipino independence following the Spanish-American War. The United States aimed to spread their influence past their continental borders after achieving Manifest Destiny during the late 19th century. The island of Cuba and the Philippine archipelago, both Spanish colonies, became prime targets for expansion. The Philippines was economically attractive for the United States because several sea lanes from China and India passed through it. The Americans could tax ships as they pulled into port hoping to trade or resupply for their oceanic voyages. The Philippines would also give the United States a naval base in the Pacific, which could help them remain in competition with the British, Dutch, and the rapidly modernizing Japanese. When war was declared following the sinking of the USS Maine in April 1898, the United States quickly moved upon several desirable Spanish colonies which included the Philippines.[5] The United States swiftly defeated Spain in a matter of months and annexed the Philippines into its unofficial Pacific Empire.

However, the Filipinos did not want to be governed by another colonial power. The Spanish had claimed the Philippines in 1521. For almost four hundred years, the typical and discriminatory class system of Spanish colonial policy fostered deep resentment between the colonial elites in Manila and the rest of the countryside. The ideas of nationalism, which swept across the world during the late-nineteenth century, caused many educated Filipinos to call for independence. When the Spanish-American War broke out, the Americans claimed to support the Filipino revolutionaries but left them out of the peace negotiations. Many saw this as the transition of power from one colonial entity to another. Following the murder of a Filipino soldier by an American and President McKinley’s declaration of “benevolent assimilation,” the Filipinos declared their independence and established the First Republic under President Emilio Aguinaldo in 1899. However, American firepower proved too much for the Filipino Army and Aguinaldo had to resort to guerilla fighting. Despite their valiant effort, the First Republic fell after three years of fighting, though pockets of heavy resistance in individual provinces would remain until 1911.

While the Filipinos fought against the United States, a third combatant- cholera- joined the conflict in March of 1902. While not a colonial power, it was also greatly feared. From 1837 to 1901, cholera was one of the diseases that defined the Victorian era. It stalked the streets of London, the trenches of Sevastopol, and the jungles of the Philippines. Of all the variants of cholera, Asiatic cholera was the most feared.[6] Infection occurred when a person consumed water contaminated with fecal matter containing cholera. What made it deadly was its high mortality rate, 85% on average between the ages of 5-45 in some cases, due to the loss of water and electrolytes from intense vomiting and diarrhea.[7] Allegedly, the epidemic started when some Filipinos ate jettisoned cabbage that washed ashore on the banks of the Pasig River from an infected Cantonese trading ship.[8] The validity of this origin could be disputed since the cabbages were allegedly floating in the sea, but Major Woodruff, a United States Army Surgeon, wrote that: “If there is cholera, typhoid, dysentery, or any similar infectious disease in the community, the bacteria are deposited in the cracks and crevices of the leaves of cabbages, celery, lettuce, and such vegetables, and if they are eaten uncooked, the disease is spread…”[9] This indicated that American medical officials recognized that one of the possible transmission vectors of cholera was contaminated water hidden in imported produce. Additionally, the report of the banca arriving in Tobagan in 1902 suggested that cholera was already present in Leyte two months before the official start of the epidemic, indicating that March of 1902 may not be the true start of the spread. Regardless of how the epidemic began, it quickly metastasized throughout Luzon and more importantly, Manila, the colonial capital of the Philippines. With American troops and ships passing through the capital either on leave or on campaign to subjugate the rebels, cholera inevitably followed them.

Despite the prevailing narrative that the 1902 Cholera Epidemic took place after the end of the Philippine-American War, cholera was transmitted through the American policy of “concentration,” or the forced relocation of civilians into designated zones during the war.[10] The difficulty of fighting a guerilla war was that guerillas often did not identify themselves as combatants. Instead, they blended in with the civilian population. Therefore, colonial regulars could not distinguish between the innocent and the enemy. Their solution was to remove the civilians from areas with a clear guerilla presence and secure them in camps or “zones” under military surveillance, like Spain and Britain had in their struggles against their rebels.[11]

Cholera proliferated due to the abysmal conditions within these concentration zones. These zones were often overcrowded.[12] When the policy of concentration was enacted on December 8, 1901, hundreds of peasants from the countryside were herded into these pre-established zones.[13] In one of these zones, thirty thousand people were squeezed into an area fit to serve three thousand.[14] The overcrowding aided in the spread of cholera in two ways. Firstly, the lack of space between people meant that if one person in a house or hut got infected, the entire home was likely to be infected. Given the proximity of people, disease could easily jump from person to person, house to house. Secondly, clean water sources were limited given the large populations of people in each of these zones. If contaminated fecal matter got into a water source, dozens, if not hundreds, of people could be infected before the first death. Overall sanitation was also poor. In a photo taken around 1900 titled, “A Sewage-clogged Drainage Ditch,” drainage ditches were displayed, full of human waste and debris that were uncomfortably close to the huts where people ate and slept.[15] If those ditches overflowed due to clogging or heavy rain, contaminated waste could spill into rivers, fill wells, or seep into groundwater. Waste-filled water could also flow into the nearby houses. If this situation occurred, any wet surface within the home might harbor cholera. Transmission could be as easy as a child touching a wet surface before putting their hands in their mouths. Malnutrition resulted from the lack of access to food and scarce medical supplies because the American regulars and Filipino guerillas needed them. This compromised the immune systems of those who lived in the zones. A weakened population meant increased infection rates.

Another way that cholera spread in the zones was the use of a “water cure” by American troops. Since guerillas and civilians often intermingled, it was likely that civilians had information on weapon caches, names of known guerillas, etc. However, local Filipinos were not inclined to betray their neighbors. Therefore, the Americans resorted to interrogating suspected sympathizers or known guerillas to extract intelligence. Water cures were a method of interrogation where a group of three to four men held a captive down while a fifth poured water into the captive’s mouth.[16] This was an early form of waterboarding. Though photos at the time claimed that water cures were harmless, the counterclaims became so numerous that they prompted a Senate hearing in 1902.[17] William Taft, provincial governor of the Philippines and future President of the United States, admitted water cures were a type of torture.[18] This gained the attention of the international community since the Americans took an official anti-imperialist stance. In a Life Magazine cover, a representation of the other colonial powers said, “Those pious Yankees can’t throw stones at us anymore.”[19] Since clean water was reserved for American soldiers to drink, interrogators most likely used water from contaminated sources within the zones. These contaminated sources included waterways contaminated by sewage runoff or, in extreme cases, drainage ditches. If a person in a concentration zone managed to escape contaminated cholera by only drinking disinfected water, cholera could instead be forcibly introduced into their system if the Americans suspected them.

The conditions and actions taken within the zones caused cholera to multiply at a rapid rate. When infected individuals were released, cholera then spread into the countryside. According to data compiled from the Libros de Entierros, 31 out of 637 people died in April in Batangas City from diarrhea.[20]While this did not provide conclusive evidence that cholera was the cause of death, diarrhea was one of the symptoms associated with cholera. With the official start of the epidemic occurring in March, it was plausible that cholera had been misidentified or even rejected as a cause of death given the fear American officials had regarding cholera.[21] At the end of the month, the policy of concentration was lifted.[22] The people within those zones could return home. As a result, a high concentration of infected individuals spread across Batangas contaminating other sources of water and villages as they went, moving cholera into previously untouched populations. By June, the number of the dead had doubled in Batangas City, but the cause of death was clearly marked as cholera by this time.[23] In another zone, Lipa, cholera became the second largest cause of death, accounting for 202 deaths out of 1329. With the end of hostilities still a month away, the Americans did not proactively fight cholera in the countryside, which instead allowed the disease to remain unchecked until Roosevelt’s declaration.

Filipino actions during the war also contributed to the spread of cholera. J.C. Perry, Surgeon General and Chief Quarantine Officer in the Philippines, wrote in a medical report in August of 1902: “The provincial and municipal boards of health, composed of Filipino physicians, have proved to be entirely incompetent to meet the emergency of dealing with an epidemic… controlling the disease… has been accomplished by (US) army surgeons.”[24] Here, Perry stated that local endeavors to control the epidemic failed with success being attained after martial authority overrode local jurisdiction. While his words were tainted with a negative attitude common among colonizers to the colonized, there were some legitimate reasons why the Filipinos failed to enforce an epidemic response. As an island nation, ships, boats, and other watercraft, traveled between the islands. Any known, or suspected, cholera infection, was denied permission to dock/land (as seen in the case of the banca in the introduction). Ships that could dock were quarantined upon arrival and inspected by port authorities.[25] A report written in June of 1902 displayed that quarantine inspections included the quarantine and disinfection of crew, passengers, and baggage.[26] Data from May 1900 indicated that the United States had been implementing these quarantine procedures before the cholera epidemic started. So, why was it so difficult for the United States to maintain quarantines? Many Filipinos traveled freely between the islands as fishermen or banca drivers with intimate knowledge of local beaches. Additionally, smugglers obtained goods and/or people from ships that were denied safe harbor on the islands.[27] Furthermore, as shown in the introductory anecdote, some open ports were a short distance away from closed ports. This fact demonstrated that quarantine procedures were not uniformly implemented across the country. Since the Americans were preoccupied fighting a war, enforcement of quarantine fell upon local authorities, who may not have been keen in obeying a foreign power that betrayed them or kept their ports open for other economic or social reasons. These factors defeated the port quarantines, as the locals, unknowingly harboring cholera, could land almost anywhere on the archipelago and bypass the intensive procedures performed at the ports.

Another instance of Filipino actions was the concealment of infection and death from American authorities due to taboos and fear of property loss. The frustrated tone of American officials attempting to combat cholera was echoed by J.C. Perry in the previously mentioned medical report in August of 1902: “They (Filipinos) will adopt every measure to conceal the cases and throw every obstacle in the way of the authorities in their attempt to suppress the disease.”[28] In this passage, J.C. Perry placed the blame squarely on the Filipinos for obstructing the reports of cholera cases. However, they had good reason to hide cholera cases from the Americans. As the bodies piled up there was no way to maintain proper burials. American health officials ordered a halt on burials for fear of infecting the water table.[29] The most efficient way to get rid of the disease was to burn everything suspected to have cholera, which included corpses. This policy, enacted in the first two months of the epidemic, faced strong opposition from the Filipinos for two reasons.[30] Cremation was viewed as taboo due to local religious beliefs dictating that a person must be buried on consecrated ground and not be disfigured through burning.[31] The burning of infected individuals’ homes also led to an increase in the population within concentration zones as families located in or near the homes of the sick would be forcibly sent there.[32] Additionally, the poor were disproportionately affected by the burning of ‘contaminated’ homes. The Americans seemed to be very calloused in their fight against cholera. According to a sympathetic American teacher, the poor were often left homeless for at least six months as the American administrators dawdled paying for the rebuilding of burnt homes.[33] Those funds generally never made it into the hands of those whose homes were destroyed. They were instead allocated to fighting the insurrection or to other projects in the Philippines. If the families were relocated to a concentration zone, their chances of death from malnutrition or disease were high. Given these factors, bodies were buried in secret in backyards, rice fields, or dumped into the Pasig River.[34] The bodies likely were not cleaned before disposal, exposing water tables, as well as food and water sources to contaminated bodily fluids. Despite the extreme measures for combating cholera being lifted at the end of July, concealment of bodies and failure to report cases continued.[35]

The 1902 Cholera Epidemic should not be viewed as a result of war. It had been occurring in tandem with the Philippine-American War. The Americans had a direct hand in spreading the disease through their policy of concentration that was justified by the practical need to deny Filipino guerillas of support, to segregate civilians from combatants, and the altruistic desire of the Americans to civilize the Filipinos. These policies decreased cooperation with Filipinos by causing them to disregard the authority of the United States or to secretly dispose of cholera ridden corpses due to the fear of cremation, homelessness, and relocation to concentration zones which served to spread the disease further. While the epidemic would continue until 1903, with sporadic cases occurring in subsequent years and rebellions against the Americans would continue until 1911, the relationship between that of the cholera epidemic and the Philippine Insurrection was not one of cause and effect; rather it was an event that was inevitable regardless of war, and was unknowingly fueled by anti-guerilla policies.

Endnotes

[1] A banca is a type of boat similar to a kayak with a floatation “wing” made of bamboo, attached to the port and starboard side, with an optional sail.

[2] H.A. Stanfield, J. C. Perry, and P. A. Surg, “PHILIPPINE ISLANDS. Origin of Cholera in Cebu with Report of Cases and Deaths,” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 17, no. 36 (1902): 2074-2075.

[3] Ken De Bevoise. “Cholera: The Island World as an Epidemiological Unit,” Agents of Apocalypse: Epidemic Disease in the Colonial Philippines (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), 164.

[4] “GENERAL AMNESTY FOR THE FILIPINOS; Proclamation Issued by the President. COMPLETE CIVIL CONTROL: Restoration of Peace Declared and Gen. Chaffee Relieved as Military Governor-The Army Eulogized,” New York Times (New York, NY), July 4, 1902.

[5] This event was largely seen as an accident by contemporary historians, but it appeared that the United States had been planning to go to war with Spain for some time and the sinking of the Maine was used to justify going to war.

[6] Bevoise, “Cholera: The Island World as an Epidemiological Unit,” 164.

[7] Refer to Table 4 in Victor G. Heiser, “The Outbreak of Cholera in the Philippines in 1905. The Methods Used in Combatting It, With Statistics to Jan. 1, 1906,” JAMA 48, no. 10 (1907): 857.

[8] Bevoise, “Cholera: The Island World as an Epidemiological Unit,” 176.

[9] Charles E. Woodruff, “Cholera and Infected Waters,” JAMA 45, no. 16 (1905): 1160.

[10] Glenn A. May, “The ‘Zones’ of Batangas,” Philippine Studies 29, no. 1 (1981): 89.

[11] Iain R. Smith and Andreas Stucki, “Colonial Development of Concentration Camps (1868-1902),” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 39, no. 3 (2011): 417.

[12] Refer to photo and caption found in Arnaldo Dumindin, “The Last Holdouts: General Vicente Lukban Falls. Feb. 18. 1902,” Philippine-American War, 1899-1902, 2006, accessed May 4, 2021, https://www.filipinoamericanwar18991902.com/thelastholdouts.htm.

[13] This was a photo of Batangas Zone residents indicating that this photo was taken during the beginning of 1902.

[14] May, “The ‘Zones’ of Batangas,” 99.

[15] “A Sewage-clogged Drainage Ditch,” Office of Medical History. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/spanam/gillet3/illustrations.html.

Note: The contents of the database have photos concerning the Philippine-American War and the 1902 Cholera Epidemic. Though the photo itself does not have a publication date, it can be assumed that this picture was taken between 1899-1902.

[16] Refer to photo in Paul Kramer, “The Water Cure,” February 17, 2008, accessed May 16, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/02/25/the-water-cure.

Note: The caption underneath the referenced photo states that it was allegedly taken in May of 1901, right in the middle of the Philippine-American War.

[17] “Water Cure,” Getty Images, accessed April 20, 2021, https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/group-of-american-soldiers-applying-the-water-cure-upon-a-news-photo/525582883.

Note: This image was cited to be taken around 1900 and published in a book in 1902.

[18] “Affairs in the Philippine Islands: Hearings Before the Committee … [Jan. 31-June 28, 1902] April 10, 1902. Ordered Printed as a Document (Washington D.C., United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1902), 75.

[19] Refer to photo in “Waterboarding – The U.S. Military in the Philippines – 1902,” View from the Left Bank: Rob Prince’s Blog, May 31, 2015, https://robertjprince.net/2014/04/05/waterboarding-the-u-s-military-in-the-philippines-1902/.

[20] Refer to Table 2 on May, “The ‘Zones’ of Batangas,” 98.

[21] Bevoise, “Cholera: The Island World as an Epidemiological Unit,” 180.

[22] May, “The ‘Zones’ of Batangas,” 89.

[23] May, “The ‘Zones’ of Batangas,” 101.

[24] J.C. Perry, “PHILIPPINE ISLANDS. Reports from Manila-Cholera in the islands,” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 17, no. 39 (1902): 2240-2241.

[25] J.C. Perry, “PHILIPPINE ISLANDS. Report on Cholera in the Philippines for the Three Weeks Ended July 12, 1902,” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 17, no. 37 (1902): 2130-2135.

Note: This directive was given in July of 1902 in the middle of the cholera epidemic. This was created so that uninfected ports could be spared of cholera.

[26] J.C. Perry, “PHILIPPINE ISLANDS. Quarantine transactions in the Philippines during May 1900,” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 17, no. 33 (1902): 1914.

[27] Bevoise, “Cholera: The Island World as an Epidemiological Unit,” 177.

[28] Perry, “PHILIPPINE ISLANDS. Reports from Manila-Cholera in the islands,” 2240.

[29] Reynaldo C. Ileto, “Cholera and the Origins of the American Sanitary Order in the Philippines,” Imperial Medicine and Indigenous Societies (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2017), 137.

[30] Ileto, “Cholera and the Origins of the American Sanitary Order in the Philippines,” 136.

[31] Ileto, “Cholera and the Origins of the American Sanitary Order in the Philippines,” 137-138.

[32] Ileto, “Cholera and the Origins of the American Sanitary Order in the Philippines,” 136.

[33] Ileto, “Cholera and the Origins of the American Sanitary Order in the Philippines,” 136.

[34] Ileto, “Cholera and the Origins of the American Sanitary Order in the Philippines,” 138.

[35] Ileto, “Cholera and the Origins of the American Sanitary Order in the Philippines,” 138.