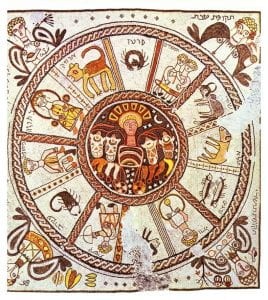

Photo of the Bet Alpha Synagogue Mosaic Zodiac retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaic_Zodiac_from_Synagogue_in_Beit_Alpha,_Israel,_6th_Century_%2831858682362%29.jpg

By Roy Harel

The function of Palestine’s late antique synagogue mosaics is a contentious topic among scholars. Some scholars say the mosaics provide vital information about local Jewish cultural traditions and beliefs, while other scholars state the zodiac mosaics are merely decorative. Late antique synagogue mosaics were the artistic products of cross-cultural interaction that took place in the diverse microcosm of cultures and religion in the eastern Mediterranean to the Near East. The interactions between Jewish communities and other regional groups led to the creation of these late antique synagogue mosaics that were found in Palestine. Controversially, these mosaics frequently featured elements and motifs that were unmistakably non-Jewish or polytheistic mosaics repeatedly featured components and motifs like the pagan zodiac wheel and the image of Helios. The late antique zodiac mosaics from the Bet Alpha synagogue, John Chrysostom’s polemical sermons, and the chancel screens from Hammat Gader and Masu’ot Yitzhaq reveal that identity and cultural association were more fluid than previously thought in late antique Palestine. The Jewish community that commissioned them was defined by a synthesis of Jewish and Roman identities, in which both identities intertwined but remained distinct.

In Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Land of Israel, Rachel Hachlili explored the origins, diverse cultural influences, and artistic styles of Jewish art, ranging from the Hellenistic period through the late antique period. Hachlili particularly investigated the contexts and meanings of the zodiacs unearthed within late antique synagogues. She asserted that the cultural connections between the two crucial Greco-Roman cities of Alexandria and Antioch, two significant Jewish cultural centers throughout the Roman era, allowed for Jewish communities in Palestine to absorb the zodiac and other non-Jewish artistic components into their art.[1] Regarding the function of the synagogue zodiac wheels, Hachlili argued that “the Jewish zodiac mosaic functioned as a calendar.”[2] She suggested that the twelve signs stand in for the twelve months of the year, Helios stands in for the day and the background behind him represents the night.[3] Consequently, she examined how elements of the zodiac may have been altered to reflect elements of the Jewish calendar. She refuted that the zodiacs could not have been simply ornamental because “the fact that the zodiac was used many times makes it clear that the Jewish community was not interested merely in a strictly decorative design.”[4] As a result, Hachlili’s book suggests that Jewish communities in Late Antiquity used the zodiac as more than just decoration, using it as “a significant framework for the annual synagogue rites.”[5] Thus, her research reflects the zodiac’s active role in late antique Jewish religious life, as a calendar directly responsible for the regulation of ritual activity. Ultimately, she believes that the cultural diffusion between the Levant and the greater Greco-Roman world facilitated the incorporation of Jewish and pagan symbolisms into the mosaic.

Jodi Magness’s position is comparable to Hachlili’s perspective on ancient Palestinian synagogue mosaics. In Heaven on Earth: Helios and the Zodiac Cycle in Ancient Palestinian Synagogues, Magness analyzed the earlier work of Erwin R. Goodenough, a scholar who studied symbols and elements in Jewish art and during the Classical Period and Late Antiquity, to reach a conclusive interpretation of the perplexing synagogue zodiacs.[6] To find a definitive interpretation, Magness thoroughly examined the findings from several synagogues, notably Hammath Tiberias, Sepphoris, and Bet Alpha.[7] Magness ultimately argued that the figure of Helios, which appeared within many zodiac mosaics, was meant to “represent Metatron, the divine super-angel.”[8] Coupled with this assertion, she interpreted that the Jewish zodiac mosaics were a key component of a mystical Judaism that opposed Rabbinical authority.[9] Furthermore, she also noted the “consistent and universal use of Hebrew instead of Aramaic or Greek in the labeling of certain figures in the mosaic floors of synagogues, including the signs of the zodiac and the four seasons.”[10] Consequently, Magness’ reading of the material evidence positions the zodiacs as central elements for a specific kind of Jewish ritual practice that thrived in late antique Palestine.

Walter Zanger proposed a different perspective from Hachlili and Magness on the zodiac mosaics in “Jewish Worship, Pagan Symbols: Zodiac Mosaics in Ancient Synagogues.” As a rabbi and an academic, Zanger utilized his knowledge of various topics from Jewish history and archaeology to provide invaluable insights in the debate over late antique synagogue zodiac mosaics. Zanger asserted that the zodiac wheels of late antique synagogues were “just decoration, pretty pictures, the common designs of the era,” rather than designs endowed with some deeper meaning.[11] He centered this argument around the investigation of the famous mosaic carpet discovered at the Bet Alpha Synagogue.[12] First, he explained the limitations placed on figurative representation in Jewish scripture. Then, he addressed the problem posed by the existence of zodiacs within synagogues, which he noted as a symbol of pagan religion.[13] Zanger used Hachlili’s words by stating that these zodiacs were merely decorative.[14] He defended his position by stating that the Bet Alpha zodiac is an example of “…clumsy astronomy…” and that the person who created the mosaic “…hadn’t a clue about real astronomy or astrology, doubtless because he was a Jew and couldn’t care less.”15 This interpretation is clear due to the the misplaced seasons on the zodiac and other zodiacal symbols that don’t align with dates on the calendar, Jewish holidays, and festivals.16 Zanger’s rigid claim that the zodiac’s sole purpose is merely aesthetic reveals his traditionalist perspective of identities in late antique Palestine, where the lines dividing Jews, Romans, Christians, and other groups were distinct and well-defined.

Alternatively, Lee I. Levine supports an entirely different viewpoint concerning the purpose and context of the synagogue zodiac mosaics. Levine’s work, Visual Judaism in Late Antiquity: Historical Contexts of Jewish Art, examines the historical circumstances of Jewish art and imagery from the time of the Bible, through Late Antiquity to the rise of Islam.[15] Notably, Levine’s interest in the evolution of Jewish art in Late Antiquity led his research to the zodiac mosaics discovered in Jewish synagogues and other zodiac mosaics excavated in other areas of the Roman world.[16] Levine highlighted the numerous hypotheses and ideas put forth by academics concerning the ambiguous contexts of the zodiacs, including its capacity as an aesthetic object, a practical ritual calendar, and a courier of a messianic message.[17] Ultimately, his research led him to conclude that the adoption of the zodiac and the figure of Helios, a Greek god that frequently accompanied it, resulted from a Jewish community reacting to Christianity’s ascent to religious dominance.[18] Levine further argued that the zodiac and other similar elements found in Jewish ritual spaces show that the communities who commissioned them had somewhat embraced Greco-Roman cultural habits, along with their aesthetic and visual components.[19}

There has been much discussion and speculation over the murky function, history, and significance of the zodiac mosaics found in late antique synagogues in Palestine. Scholarly discussions debate whether the zodiac was used as a seasonal calendar as well as a focus on the potential artistic preferences of community members in late antique Jewish communities. I agree with the scholarship which argued that the zodiac did indeed have a significant functional role in Jewish ritual life in Late Antique Palestine. In my research, I demonstrate that the Jewish community that commissioned these zodiacal mosaics was defined by a synthesis of Jewish and Roman identities, in which both identities intertwined but remained distinct from one another.

The impact of images and impassioned speeches on identities

Persistent cultural exchanges among the various ethnic groups that inhabited the Mediterranean world characterized Late Antiquity. No other region of Late Antiquity displays this feature more clearly than the Roman Empire’s “cultural powerhouse,”[20] which was the eastern Mediterranean and the Near East.[21] This area was a frontier, where the Sassanian Empire and the Roman Empire converged. [22] It also was where communities of Christians, Pagans, Jews and others lived, resulting in widespread cultural and religious synthesis.[23] Cross-cultural synthesis in the Levant took many artistic and religious forms of expression during Late Antiquity, such as through the creation of zodiac mosaics.

The zodiac mosaics are the result of the cultural diffusion that took place within late antique Palestine. These zodiacs introduced elements, such as the zodiac signs themselves and the central image of Helios, into Jewish religious spaces, creating a previously unknown form of religious expression. The first of these zodiacs seems to have been made at the site of Hammath Tiberias, followed by the production of numerous other zodiacs across Jewish centers in the Galilee during Late Antiquity.[24] The mosaic carpet and zodiac discovered at the ruins of Bet Alpha was located and excavated in 1929 by the preeminent archaeologist Eleazar Sukenik.[25] The Bet Alpha mosaic carpet provides an invaluable source of information concerning late antique Jewish society in Palestine, a community that had remained frustratingly mysterious for scholars. This community’s synagogue including Greco-Roman mythological figures in their mosaics are part of the reason why scholars have had difficulties understanding the late antique Jewish community in Palestine.

The Bet Alpha mosaics in the Galilee were excavated within the ruins of a sixth-century synagogue.[26] This ancient synagogue’s floor entrance is ornamented with three differently-storied mosaic panels, and around them lay geometrically ornate floral designs.[27] At the bottommost panel of the mosaic floor lays a bilingual mosaic inscription, the upper part of the inscription in Greek, the lower portion in Aramaic.[28] The use of both Greek, the dominant language of the eastern Mediterranean, and Aramaic, the language of the Levant, suggests that the Bet Alpha Jewish community was accepting of some cultural integration into the wider Greco-Roman cultural sphere while also retaining their distinct identity as Levantine Jews through the use of Aramaic.

Figure 1. “Bet Alpha Synagogue,” Nave (Inscripted Mosaic Panel), 518-527 or 567-578 C.E, Beth Alpha Synagogue, Israel, The Center for Jewish Art, Image Id. no. 1658, https://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php?mode=alone&id=1658

The bilingual inscriptions on the zodiac mosaic also provide valuable insight into the cultural identity of the late antique Jewish community in Palestine. The carved Greek inscription roughly translates to, “may the craftsmen who carried out this work, Marianus and his son Hanina, be held in remembrance.”[29] Marianus sports a typical Greco-Roman name, while his son bears a bilingual mosaic inscription that is more traditionally Jewish ‘Hanina.’ These inscriptions reveal their Jewishness and demonstrate how integrated their cultural and religious ties are to a larger Roman sphere of influence. These names further imply that the Jews of the late antique Galilee represented a synthesis of Jewish and Roman cultures. The names of the artisans who worked on this mosaic likewise provide insight into Bet Alpha’s cultural orientation. The translated Aramaic inscription reads: “This mosaic was laid down in the year … of the reign of Emperor Justinus … who gave a hundred dinars … gave all members (sons) of the community(?) … Rabbi … honored be the memory of all sons … Amen.”[30] The Aramaic inscription’s contents further allude to a close connection with the wider Roman world. The parts of the description utilize the reign of the incumbent emperor of the time (either Justin I or Justin II) to date the construction of the mosaic, illustrate a degree of integration into the Roman world, and enable historians to date the mosaic to the sixth century CE.

The panels of the mosaic carpet contain religious themes essential to understanding their importance. The first of the three panels of the mosaic carpet portray the famous Biblical story of the Binding of Isaac (see Figure 2). As the moral tale goes, to test the lengths of Abraham’s faith, God commanded him to sacrifice his son, Isaac, but just as Abraham was about to carry out the directive, an angel intervened and a goat was slain in his son’s place. The mosaic accurately depicts Abraham and Isaac standing next to the altar.[31] To their left, the goat or ram is illustrated standing vertically and fastened to a tree, accompanied by the words “vehine ayal” and “behold…. a ram” from the Book of Genesis. Two men who accompanied Abraham are at the furthermost left of the panel.[32]

Figure 2. “The Binding of Isaac,” Mosaic floor, 518-527 or 567-578 C.E, Bet Alpha Synagogue, Israel, The Center for Jewish Art, Object Id. no. 16, https://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php?mode=set&id=16

Since this Biblical account exemplifies Abraham’s dedication to God, it has profound significance for Jewish communities throughout history. Consequently, this story’s inclusion in the mosaic scheme suggests that the mosaic floor served a purpose beyond aesthetics. The story of the binding of Isaac holds distinct weight and religious significance for the Jewish people; thus, the mosaicked representation of the story itself is enough to indicate the community’s distinct Jewish identity. The pictures of Abraham are featured on the mosaics of other synagogues, like the one at Sepphoris; the inclusion of Abraham by himself symbolizes the physical presence of the Bet Alpha community’s Jewish identity.[33] The Binding of Isaac, however, holds a crucial function in the liturgy and cultural memory of the Jewish people. The narrative of Abraham nearly sacrificing his son as an act of obedience to God, and God’s subsequent intervention,[34] grants the mosaic panel special significance and emphasizes the Jewish heritage of the Bet Alpha community.

Figure 3. “Bet Alpha Synagogue,” Mosaic floor, 518-527 or 567-578 C.E, Hephziba, Israel, Beth Alpha Synagogue, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Image Id. #737, Index of Jewish Art: Center for Jewish Art, 1994, https://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php?mode=set&id=16

The panel located near the bima, is a relatively organized cluster of figures and creatures (see Figure 3). The mosaic’s heart is an ornate ark flanked with two menorot (seven-branched candelabras from the Jewish Temple), two lions, two lulavim, and two etrogim.[35] Each one of these visual elements holds significant religious implications. The lulavim, which are the plant-like figures situated near the arc, are a type of palm tree used in Jewish ritualistic practices during Sukkot. The etrogim are a type of citrus, which resembles a lemon and is also used in such religious practices. The ark itself is a religious reference to the ark which houses the Torah scrolls. This depiction’s menorah refers to the Menorah which resided within the Temple of Jerusalem until its destruction during the Great Jewish Revolt in 70 CE.[36] Levine explains that…“the overwhelming majority of instances display [the menorah] as a symbol with no institutional context, there is no doubt in my mind that the origin of the menorah as a common element in Jewish art stems from the menorah’s significance in Jewish ritual (lighting the interior of the Temple), as well as its nostalgic connection to the Jewish Temple, a memory of a bygone age.”[37] Therefore, the inclusion of the Menorah, alongside the other sacred Jewish events, objects, and elements discussed, provides a clear indication of Bet Alpha’s unmistakable Jewish identity.

The ark, menorot, lulavim, and ethrogim depicted in the Bet Alpha mosaic provide credence to the claim that synagogue mosaics had purposes beyond their artistic value. The ritual objects depicted (namely the ark, lulavim, and etrogim) are closely associated with Jewish religious rites. The ark holds the Torah scrolls and thus serves one of the most important roles in Jewish rituals and prayer services. The lulavim and etrogim are central elements in the holiday of Sukkot, or Feast of the Tabernacles. This topmost panel, with its three mixed zodiacal and Jewish symbols, supports the argument that the synagogue zodiac mosaics were not exclusively aesthetic but served a ritualistic function.

Figure 4. “Bet Alpha Synagogue,” Mosaic floor, 518-527 or 567-578 C.E, Hephziba, Israel, Beth Alpha Synagogue, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Image Id. #735, Index of Jewish Art: Center for Jewish Art, 1994. https://cja.huji.ac.il/image.php?id=735&m=medium

The central and most important panel of the mosaics at Bet Alpha is a zodiac mosaic consisting of a central wheel design enclosed within a square border (see Figure 4). In each of the panel’s four corners, there are four winged female figures arranged diagonally.[38] These figures are personifications of the four seasons and are appropriately labeled Nisan (spring), Tammuz (summer), Tevet (winter) and Tishri (autumn).[39] The inclusion of the seasonal figures in the panel demonstrates how the Jewish community adopted the zodiac to serve the function of a liturgical calendar; moreover, these seasonal angelic figures underscore the cultural synthesis that defined the Bet Alpha Jewish community, as they represent Jewish calendrical concepts in the context of a non-Jewish design.

The actual zodiac wheel consists of two parts: a large circle enclosing a smaller circle.[40] Situated on the zodiac wheel’s outer circle are twelve panels with animal and human figures, lined above with Hebrew inscriptions identifying each figure with a zodiac sign.[41] The Hebrew calendars’ relation with the zodiacal months affirms the belief that synagogue mosaics played a significant role in ritual life. Additionally, the descriptive Hebrew inscription for each zodiac sign signifies that the motivation behind the zodiac’s adoption originated less from purely aesthetic consideration and more toward functional religious use. The association and labeling of these signs with Jewish months and seasonal periods are indicators of Bet Alpha’s distinctly Jewish cultural background, while the labels symbolize the synthesis of multiple cultural groups.

While many designs have more culturally Jewish influence, other parts of the calendar do not. The circular panel centered within the zodiacal ring displays Helios in the center, riding a quadriga, or four-horse chariot, out of the starry night sky.[42] The majority of archeological specialists concur, that in this context, Helios is illustrated as a non-Pagan personification of the sun which… detached from the Greeks’ version of Helios or other solar deities. The Bet Alpha Helios may have similarly depicted the divine order of creation or conceivably an angelic figure like Metatron,[43] supporting the idea that the zodiac was a critical component of Bet Alpha’s ritual calendar and customs. Helios’s inclusion in synagogue mosaic art illustrates how Late Antique Jewish communities embraced the blending of their unique Jewish culture with the more general cultural identity of the Roman world.

The boundary between Bet Alpha’s Jewish and Roman identities was not as firmly defined as it may have been. The acceptance of the zodiac and Helios as acceptable motifs in the synagogue mosaics supports this idea. Using Pagan religious symbols into Jewish ritual practice also highlights the Bet Alpha community’s distinct Jewish identity. More specifically, the integration of zodiacal and pagan elements alongside firmly rooted Jewish cultural elements, shows that the predominant culture of the inhabitants of the Bet Alpha Community was thoroughly Jewish. The use of Hebrew designations and artistic elements firmly rooted in Jewish culture ultimately demonstrate that the Bet Alpha community had a concrete cultural and religious bond to the surrounding Greco-Roman world while still maintaining their fluid identity through art.

The polemical sermons of John Chrysostom (d. 407) reveal a different way of thinking about late antique cultural boundaries. Chrysostom was a notable figure in the Church and later the Archbishop of Constantinople. He began his career preaching in Antioch, the principal city and cultural hub of Roman Syria.[44] Chrysostom rose to prominence, and later infamy among modern audiences, for preaching a series of eight sermons known as Adversus Judaeos, translated as ‘Against the Jews’ or ‘Against the Judaizers.[45] Although Chrysostom’s rhetoric clearly indicated his hatred for the Jewish people, he directed his speeches towards Antioch’s Christian community because he believed they were threatened by those who wanted to “Judaize” Christianity.[46] Unfortunately, Chrysostom’s scathing sermons laid the groundwork for much rhetoric behind the antisemitism of the Middle Ages.[47] In contrast to the synagogue zodiac mosaics, Chrysostom’s polemical sermons attempt to make a clear cultural and religious distinction between the Jews and Christians.

Chrysostom’s sermons are valuable to understanding Antioch’s cultural identity and the identity of those living in the surrounding region. The first of Chrysostom’s impassioned lectures vividly illustrates his malicious rhetoric toward Jews. Chrysostom began his speech by distinguishing Christians from Jews, proclaiming that the “festivals of the wretched and miserable Jews that follow one after another in succession – trumpets, booths, the fasts – are about to take place.”[48] Chrysostom further elaborated on the distinction between Jews and Christians by claiming that “Jews were branches of the holy root, but they were lopped off [and that] We were not part of the root, yet we have produced the fruits of piety. They read the prophets from ancient times, yet they crucified the one spoken of by the prophets.”[49] By presenting Jews as depraved and impious, Chrysostom created a clear and unmistakable divide between Jews and Christians, which he likely hoped would assist in his struggle against the group he referred to as the Judaizers.

Chrysostom detested the Judaiziers because they recognized synagogues as holy sanctuaries and places where Christians could take oaths. To undermine synagogues as holy sanctuaries deserving of Christian reverence, Chrysostom disregarded the religious status they hold, claiming that “the synagogue is no better than the theater.”[50] Chrysostom also asked: “Can one not declare with confidence that the synagogue is a dwelling place of demons? God is not worshiped there. Far from it! Rather, the synagogue is a temple of idolatry.”[51] In a later message, Chrysostom asserted that “in fact, not only the synagogue but also the souls of Jews, are the abode places of devils.”[52] Chrysostom wanted to persuade his Christian audience that synagogues are heretical places that are completely opposed to Christian religious and cultural beliefs and practices through these noxious descriptions and characterizations.

The attack on synagogues in Chrysostom’s sermon was to remove a common area between Christians and Jews as well as to further distinguish and separate between them. Chrysostom’s portrayal of synagogues as centers of idolatrous demon worship alludes to the prominence of the zodiac in Antiochian Synagogues, which mainstream Late Antique Christians and early Christian theology outright condemned. It is possible that Chrysostom did not consider Pagan temples to be a relevant threat to the Roman Empire’s Christians when compared to synagogues.

Chrysostom’s rage is not directed at the synagogues but at the Christians who frequented them. He described an incident in which a “noble and free” Christian woman was forced by a possibly Christian man “into a synagogue to make an oath about certain business matters that were in litigation.”[53] Chrysostom lauds the woman’s Christian identity, portraying her as a victim who was insensibly forced into swearing an oath in a synagogue. He used this story to show that proclaiming such an oath in a temple is an action that no sensible Christian would engage in. More significantly, Chrysostom’s account of this incident shows that Christians swearing oaths in synagogues was presumably a common practice in late antique Antioch, as it may have been elsewhere in the Roman East. The commonality of such conventions mainly stems from Antioch’s substantial cultural connectedness to the broader region of Roman Syria and Palestine.[54] Chrysostom’s virulent description of the Christian woman’s plight exhibits the distinctly fluid boundaries between the many cultural groups that inhabited the region and the fact that the boundaries between the many cultural groups that inhabited the region were less distinct than Chrysostom would have preferred.

Antiochian Christian religious activities and cultural practices often involved cross-cultural and interfaith interactions with Jews. In addition to oath-taking, Chrysostom noted and detested Antiochian Christians’ reverence toward Jewish ritual spaces. According to Chrysostom, “There are some [Christians] who consider the synagogue to be a holy place.”[55] Chrysostom also asserted that certain Christians “[arrive] at a synagogue to watch [the Jews] blow trumpets.”[56] These assertions indicate that Christians may have regularly attended Jewish religious gatherings and were present in synagogues and Jewish ritual settings during periods of religious rites in the late fourth century and early fifth century in Antioch. The Christian presence at Jewish religious assemblages and temples suggests that interfaith religious and cultural interactions were more commonplace than one might assume.

In Religious Identity in Late Antiquity, Isabella Sandwell, a specialist in late antique Christian and non-Christian theology and ethnography, contended that Chrysostom mindfully produced distinctions between his Christian audience and non-Christian neighbors in Antioch.[57] More specifically, Sandwell explains that “by painting a vivid image of the supposed idolatrous past of the catechumen, Chrysostom could exaggerate and clarify the boundary between idol-worshiper and Christian.”[58] Consequently, Chrysostom’s obsessed demarcation between Christians and non-Christians implies that the boundaries between cultures in Antioch and the wider region were blurry to a degree and less distinctive.

The first of Chrysostom’s eight polemical sermons offers a crucial perspective on the late antique cultural environment of the eastern Mediterranean. The stakes involved in cultural identity in the area are underscored by his vehement language, where he criticized the behavior of “Judaized” Christians. Chrysostom believed it was his duty to prevent what he viewed as the Christians’ departure from a devout path because of the ongoing lack of distinction between Antioch’s Jews and Christians. However, Chrysostom’s sermons demonstrate the flexibility of cultural identification for many in the late antique Roman East for contemporary researchers. His scathing speeches demonstrate that the dissimilarities between Christians, Romans, and Jews that modern scholars attribute to them are relatively antiquated and do not entirely reflect how communities and populations in late antique times perceived themselves.

While John Chrysostom’s scathing sermons emphasize the glaring absence of concrete cultural identity distinctions between Jews and other populations in the Roman world, the material evidence excavated by archaeologists reflects an opposing perspective. The Jewish and Christian chancel screens discovered at Hammat Gader and Masu’ot Yitzhaq, are one example of tangible evidence that reveals the state of cultural identities in late antique Palestine.[59] By the end of Late Antiquity, holy sites began to use marble-constructed chancel screens to separate areas like a synagogue’s bima and a church’s podium from the rest of the room.[60] The square colonnettes placed throughout the carved and ornamented marble slabs of the chancel screens were held fast by grooves that ran along their sides.[61] In Palestine, these constructions were present in Jewish and Christian spaces throughout Late Antiquity, as noted earlier. These archeological sources are an excellent source for studying cultural interactions and the fluidity of identity at the time.

Figure 5. “Chancel Screen with Cross,” Marble Slab, 6th-century C.E, Massuot Yitzhak, Negev, The Israel Museum, David Mevorach, I.A.A 1953-4, The Israel Museum, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2005. https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/222825-0

In Hammat Gader, in the Golan Heights, a Jewish example of a chancel screen slab was found(see Figure 5).[62] The slab was not unduly ornamented; it had a simple linear border and a wreath picture in the middle.[63] Additionally, the laurel wreath’s center included a blossom-cross carving.[64] The Menorah, a seven-branched candelabra that was once kept in the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, is depicted in the wreath’s center.[65] A modern Christian chancel screen was discovered at the Masu’ot Yitzhaq site in southern Palestine.[66] The chancel screen from Masu’ot Yitzhaq had a plain linear border, similar to the Hammat Gader screen.[67] In contrast to its Hammat Gader twin, the Masu’ot Yitzhaq slab was more ornamented. The Christian chancel screen included crosses on either side of a wreath in the center.[68]

Oil lamps are another example of suggestive physical evidence regarding the issue of identities and cultural associations during Late Antiquity. For nearly all of Near Eastern history, oil lamps were a ubiquitous part of life. They were critical elements of religious practice, as the menorah was composed partly of seven oil lamps. In Jerusalem, archeologists discovered many oil lamps with Jewish and Christian roots.[69] The general design of two instances of these lamps from Jerusalem—one Jewish and one Christian—is relatively similar. However, the affixed insignia that are affixed to them vary. The Christian oil lamp has a massive cross in its design, whereas the Jewish oil light is embellished with a Menorah.[70]

Although the general patterns of the two chancel screens and oil lamps are comparable, the distinctions between the two are particularly illustrative of the level of cultural identification in late antique Palestine. More precisely, the differences in the features present on the slabs and lamps show that the boundaries between different cultural groups and identities were distinct and well-defined than they would initially appear. The menorah became a significant and distinctively Jewish emblem during Late Antiquity, appearing on paintings, columns, and mosaics.[71] It gained popularity due to its connection to the Temple of Jerusalem, reflecting a sentiment of spiritual longing for the Jewish communities of Palestine. At the same time, the cross also became a dominant symbol for the growing Christian faith and was used to conjure up the idea of a spiritually charged remembrance of Christianity’s origins.

The menorah and the cross became symbols that represented values unique to the cultural and religious groups that adopted them. Thus, it is possible that using these two symbols helped distinguish between cultures. The distinctive, culturally specific symbols differentiate the Jewish and Christian versions of the chancel screens and oil lamps, with the rest of their general designs being nearly identical. Although late antique cultures shared lamps and chancel screens, the usage of unique cultural symbols shows that there was conscious separation and demarcation between Jews and Christians.

Late antique Near Eastern material culture and literary evidence reveals that identity and cultural association were much more fluid than they previously seemed to be. The designs of the Bet Alpha mosaics, John Chrysostom’s polemical sermons, and the late antique chancel screens and oil lamps, demonstrate that cultural and religious identification were extremely flexible but there was still some degree of group differentiation that stubbornly persisted. The usage of the zodiac and Helios in the Bet Alpha synagogue mosaics underscore the fluidity of religious identification and cross-cultural influence in the Near East. Despite past scholarship relying on Chrysostom’s sermons which made clear divisions between Christians and Jews, his sermons actually reveal that there were numerous occasions of interfaith interactions and cultural practices that were influenced by another cultural group. However, the persistence of Jewish and Christian symbols on late antique chancel screens and oil lamps showed that there was a conscious demarcation and distinction between Jews and Christians.

Endnotes

________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Rachel Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Land of Israel, (Leiden: E.J Brill, 1988), 368-369.

[2] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 308-309.

[3] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 309.

[4] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 309.

[5] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 309.

[6] Jodi Magness, “Heaven on Earth: Helios and the Zodiac Cycle in Ancient Palestinian Synagogues,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 59 (2005): 1–7.

[7] Magness, “Heaven on Earth:,” 4-12.

[8] Magness, “Heaven on Earth:,” 32.

[9] Magness, “Heaven on Earth,” 34-37.

[10] Magness, “Heaven on Earth,” 35.

[11] Zanger, “Jewish Worship, Pagan Symbols,” biblicalarchaeology.org.

[12] Walter Zanger, “Jewish Worship, Pagan Symbols: Zodiac Mosaics in ancient Synagogues” Bible History Daily, 2022, biblicalarchaeology.org.

[13] Zanger, “Jewish Worship, Pagan Symbols,” biblicalarchaeology.org.

[14] Zanger, “Jewish Worship, Pagan Symbols,” biblicalarchaeology.org.

[15] Lee I. Levine, Visual Judaism in Late Antiquity: Historical Contexts of Jewish Art, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 1-11.

[16] Levine, Visual Judaism, 225-259.

[17] Levine, Visual Judaism, 327.

[18] Levine, Visual Judaism, 335-336.

[19] Levine, Visual Judaism, 335-336.

[20] Peter Brown, World of Late Antiquity, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 19.

[21] Brown, World of Late Antiquity, 19.

[22] Brown, World of Late Antiquity, 19-20.

[23] Garth Fowden, Empire to Commonwealth: Consequences of Monotheism in Late Antiquity, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971), 61-79.

[24] Levine, Visual Judaism, 329-331.

[25] Steven Fine, Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 91.

[26] Fine, Art and Judaism, 91.

[27] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 357.

[28] “Bet Alpha Synagogue”, cja.huji.ac.il, n.d.

[29] “Bet Alpha Synagogue”, cja.huji.ac.il, n.d.

[30] “Bet Alpha Synagogue”, cja.huji.ac.il, n.d.

[31] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 357.

[32] “Bet Alpha Synagogue”, cja.huji.ac.il, n.d.

[33] Levine, Visual Judaism, 262.

[34] Levine, Visual Judaism, 283-284.

[35] Levine, Visual Judaism, 285.

[36] Levine, Visual Judaism, 55-58.

[37] Levine, Visual Judaism, 55-58.

[38] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 357.

[39] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 307.

[40] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 357.

[41] Levine, Visual Judaism, 284-285.

[42] Levine, Visual Judaism, 284.

[43] Magness, Heaven on Earth, 30-53.

[44] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers” in Christianity in Late Antiquity, 300-450 C.E.: A Reader, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), ed. and trans. by Bart D. Ehrman and Andrew S. Jacobs, 227.

[45] Levine, Visual Judaism, 179-181.

[46] Levine, Visual Judaism, 187.

[47] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers”, 227.

[48] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers,” 228.

[49] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers,” 228.

[50] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers,” 230.

[51] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers,” 230.

[52] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers,” 231.

[53] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers,” 230.

[54] Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art, 368.

[55] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers,” 232.

[56] John Chrysostom, “First Speech Against the Judaizers,” 233.

[57] Isabella Sandwell, Religious Identity in Late Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2007), 63-67.

[58] Sandwell, Religious Identity in Late Antiquity, 68.

[59] Levine, Visual Judaism, 347.

[60] Harry N. Abrams, “Chancel Screen with Menorah”, imj.org.il, 2005,

https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/222820-0.

[61] Abrams, “Chancel Screen with Menorah”, imj.org.il.

[62] Levine, Visual Judaism, 347.

[63] Abrams, “Chancel Screen with Menorah”, imj.org.il.

[64] Abrams, “Chancel Screen with Cross”, imj.org.il.

[65] Abrams, “Chancel Screen with Menorah”, imj.org.il.

[66] Levine, Visual Judaism, 347.

[67] Harry N. Abrams, “Chancel Screen with Cross”, imj.org.il, 2005,

https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/222825-0.

[68] Abrams, “Chancel Screen with Cross,” imj.org.il.

[69] Levine, Visual Judaism, 347.

[70] Levine, Visual Judaism, 347.

[71] Levine, Visual Judaism, 341-342.