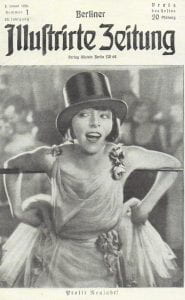

Photo of Charlotte Ritter, an energetic young woman with a strong will to succeed in her life and an example of the Weimar Republic’s “new women.”

Retrieved from https://babylon-berlin-series.blogspot.com/2018/07/charlotte-ritter-new-woman.html.

By Maria Kang

The Weimar Republic was Germany’s first attempt to establish a republic following the dissolution of its former empire after World War I. Established in 1919 within the central German city of Weimar, the Weimar Republic became the epicenter of Western European culture and innovation throughout the 1920s. Popular media often portrays the 1920s as an era of radical social change in which women shed traditional gender norms and enjoyed unprecedented economic freedom as independent workers and consumers. However, young women experienced little to no change in their personal lives as traditional expectations for women continued to prevail in Weimar society.

The postwar reality brought upon new economic changes in the Weimar Republic. Following the Prussian and Austro-Hungarian empires’ defeat in World War I, high inflation rates forced the newly established Weimar government to implement economic safety measures to protect its citizens in the face of a staggering economic crisis. The German Congress, working alongside employers and unions across industries, established a joint trilateral agreement to regulate wages, establish an eight-hour workday, and guarantee state intervention if employer-union negotiations ever failed.[1] From such policies arose a phenomenon in which “women and young people were brought into areas of the labor force from which they had formerly been excluded.”[2] Waves of young working-class women were able to enter the job market through clerical and factory positions because of the labor shortage caused by Germany’s mass casualties of soldiers during the war. After 1923, the original trilateral agreements quickly eroded in the face of decreased union membership, lacking social welfare funds as the state prioritized paying off Germany’s wartime debts, causing employer violations of the eight-hour work policy to rise.[3] In describing her workday, one girl living in Berlin wrote for a class assignment, “Day after day I enter the shop at 8:30 and don’t get home until 7:30 p.m,” while another girl mentioned that “factory workers start at 7 a.m and stop at 5 p.m,” demonstrating that it was not uncommon within various job sectors to work well beyond eight hours.[4] Thus, although the trilateral agreements represented the state’s efforts to reconstruct German society with fair policies, the realities of Germany’s postwar economy prevented effective implementation of those policies.

Women’s changing roles in Western society were often widely discussed in the mainstream. Elsa Hermann, the first Jewish doctoral student at the University of Leipzig and a well-known women’s rights advocate, noted changing attitudes towards women by comparing “the woman of yesterday” with “the woman of today.”[5] According to Hermann, the “woman of yesterday” spent her youth preparing for marriage by accumulating her dowry.[6] Once married, the woman “did as much of the household work as possible herself to save on expenses,” thereby prioritizing the collective prosperity of her family over her own.[7] They sought success by supporting their husbands’ businesses from home and managing their household expenditures to secure their children’s futures.[8] On the other hand, Hermann’s “woman of today” was inherently individualistic with the goal of “proving in her work and deeds that the representatives of the female sex are not second-class persons existing only in dependence and obedience but are fully capable of satisfying the demands of their positions in life.”[9] Shirking their responsibilities towards family prosperity, Hermann describes women in Weimar society as economically self-sufficient individuals which society “strongly inclined to characterize … as unfeminine,” because they defied the ideals emulated by “the woman of yesterday.”[10]

What led many in Weimar society to believe that women experienced unprecedented economic freedom was the disproportionate ratio of women to men both in the workforce and general population after World War I. During the war years, the rate of adult men working in factories or public workplaces dropped by about twenty-five percent while the percentage of women in the workforce increased by fifty-two percent.[11] Immediately after the war, there were 2.7 million disabled veterans, many of whom were unable to continue in their pre-war occupations due to wartime injuries.[12] Thus, the physical repercussions of war continued to reverberate throughout Germany’s post-war economy. With vacancies in administrative jobs and the adoption of new communications technologies, workplaces experienced a greater need for typists and secretaries, roles that young women could fill with minimal experience. Everyday images of young women in clerical roles reinforced Hermann’s argument that postwar social and economic conditions enabled young women to rise to white-collar status through clerical work. However, the wages women earned from these roles were ultimately not enough to achieve complete economic self-sufficiency as female-delegated work was often seasonal or temporary amidst volatile postwar economic conditions.[13]

Amongst Weimar society’s conservatives, the images of Hermann’s modern woman represented the decay of Western civilization. In an article published in the popular German magazine Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, a right-wing writer denounces such social changes throughout German society, arguing that it dangerously blurs distinctions between man and woman. Drawing upon contemporary women’s fashion trends to convey his attitude, he admits that while initially “it was like a charming novelty: that gentle, delicate women cut their long tresses and bobbed their hair, that the dresses they wore hung down in an almost perfectly straight line, denying the contours of the body,” he also argues that such trends became a social vice when fashion only “becoming to young girls and their delicate figures,” was adopted by all women.[14] The male writer reflects the traditional belief that it was acceptable for girls still in their youth to experiment with popular fashion trends, but unacceptable in adulthood. He also reflects societal fears at the time over the correlation between contemporary fashion and young women’s rejections of gender oppression stating, “it would be scarcely noticed this spring if a woman absentmindedly put on her husband’s coat.”[15]

Although the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung was a right-wing magazine, the sentiments that the magazine’s editors openly expressed demonstrated that traditional ideas of womanhood prevailed amidst radical postwar social and economic shifts. According to Hermann’s distinction of gender, “A woman is not female because she wields a cooking spoon,” but because “she manifests the characteristics that the man finds desirable, because she is kind, soft, understanding, appealing in her appearance, and so on,” which reveals that even her own feminist views at the time contained an inherently conservative tone based on traditional traits of femininity.[16] Despite Hermann’s claim that the contemporary postwar woman achieved unprecedented economic success as individuals, Weimar society as a whole viewed a woman’s working years as a brief period of their youth before they inevitably married.

Rather than changing societal values surrounding marriage, social changes during the Weimar Era merely recognized the importance of indulging in one’s adolescence during their formative years. Activities that were considered playful during adolescence became indulgent and unbecoming once the young woman married. Thus, while adolescent girls defied previous social norms of girlhood, they also took it for granted that they all would eventually marry. Reflecting on their fleeting period of youth, one schoolgirl ultimately concludes, “it can’t stay this way forever. In time things will change and I’ll start thinking about starting a family. It seems to me that when you reach your twenties, life gets more serious. Then you have to think about getting married, because going through life without a husband must be pretty dry stuff,” demonstrating that the expectation to marry remained a constant societal value.[17]

On the other hand, for many working-class women, work was not an option but a necessity to support their families. Many of them “took for granted that after leaving school at age thirteen or fourteen, one had to find a job and get used to working,” and, thus, had “very modest expectations of the free time to which they were entitled.”[18] Benninghaus compared middle-class female students’ essay responses which emphasized leisure activities such as going to the cinema with working-class students who instead focused on praising their mothers “as good housewives.” Such praises reflect “how rigid the norm of the hard-working mother still was among the working-class of the Weimar era.”[19] At this time, there was a proliferation of mass-printed “books for advice for housewives,” as well as songs and poems that praised traditional feminine qualities.[20] Young girls were being shown the traditional ideal of femininity as it was being forced upon them by economic necessity. Thus, many of these working-class students’ responses demonstrate the prevalence of normative ideas through their understanding that emerging popular culture was ultimately “opposed by parents and frowned upon by teachers and employers, as well as by some of their peers.”[21]

While still haunted by the country’s defeat in World War I, the Weimar Republic was a complex society driven by technological innovation. Although upper-class women enjoyed higher degrees of socioeconomic freedom, most young women continued to uphold traditional domestic roles as housewives and mothers. The lack of workforce labor and emergence of stenography, typewriting, and telephone technology opened new doors of opportunity for many women in cities. However, Germany’s postwar reparations and fluctuating inflation rates led to poor economic conditions, leaving many working-class women no choice but to work long hours for meager wages in unstable jobs.

Despite Elsa Hermann’s claim that shifted attitudes enabled the women of Weimar Germany to thrive with their newfound independence, traditional prewar gender norms continued to prevail. Outside of the more educated circles of German society to which Herrmann belonged, conservative criticism of women’s increased freedom of expression and action dominated Weimar society as many considered this a sign of the decay of Western civilization. In fact, under the Third Reich during the 1930s, the Nazi Party warned against this blurring of gender roles and strongly advocated for the return of women to the domestic sphere.

Though traditional values of womanhood continued to dominate society, a new concept of indulgent youth did emerge during the interwar period. Society was more tolerant of young women’s participation in popular culture and leisure activities. However, underlying such tolerance existed the assumption that those frivolities would inevitably end as women married and settled into expected roles of domestic life and motherhood. Thus, despite the popular assumption that 1920s Western culture represented an era of sexual revolution for women, a closer look at the Weimar Republic demonstrates that even within a cultural epicenter of the interwar period, traditional values continued to dominate society.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Mary Fulbrook, A Concise History of Germany (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 171.

[2] Fulbrook, A Concise History of Germany, 157.

[3] Fulbrook, A Concise History of Germany, 157.

[4] Christina Benninghaus, “Mothers’ Toil and Daughters’ Leisure: Working-Class Girls and Time in 1920s Germany,” History Workshop Journal, no. 50 (Autumn, 2000): 50.

[5] Elsa Herrmann, This is the New Woman, translated in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, edited by Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, and Edward Dimendberg. Berkeley: University of California Berkeley, 1994, accessed 13 November 2021, 1. https://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=3887.

[6] Herrmann, This is the New Woman, 1.

[7] Herrmann, This is the New Woman, 1.

[8] Herrmann, This is the New Woman, 1.

[9] Herrmann, This is the New Woman, 2.

[10] Herrmann, This is the New Woman, 2.

[11] Robert W. Whalen, “War Losses (Germany) | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1),” in 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. edited by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, October 8th 2014, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/war_losses_germany.

[12] Robert W. Whalen, “War Losses (Germany) | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1).”

[13] German History in Documents and Images, “Unemployed Stenotypist Seeks Work,” accessed 14 November 2021. https://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_image.cfm?image_id=4102.

[14] “Enough is Enough! Against the Masculinization of Women,” translated in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, edited by Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, and Edward Dimendberg. Berkeley: University of California Berkeley, 1994, accessed 13 November 2021, 1. https://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=3881.

[15] “Enough is Enough! Against the Masculinization of Women,” 1.

[16] Herrmann, This is the New Woman, 2.

[17] Benninghaus, “Mothers’ Toil and Daughters’ Leisure,” 56.

[18] Benninghaus, “Mothers’ Toil and Daughters’ Leisure,” 49.

[19] Benninghaus, “Mothers’ Toil and Daughters’ Leisure,” 59.

[20] Benninghaus, “Mothers’ Toil and Daughters’ Leisure,” 21.

[21] Benninghaus, “Mothers’ Toil and Daughters’ Leisure,” 21.