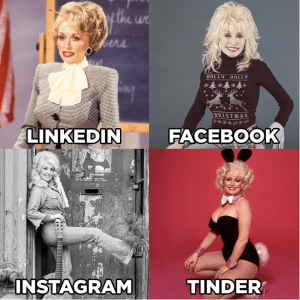

Beyond the basic profile generation questions, social media accounts allow further customization options, such as the addition of a profile photo and biography. The creative diversity built into the very foundations of social media technology affords participants and users of all backgrounds and intentions to create a networked space, a “digital body,” as boyd calls it, that is both indicative of a person and “the product of a self-reflexive identity production” (125). This is where the concept of “writing oneself into being” comes into play.

danah michele boyd writes on teenagers’ participation in MySpace through their profile creation and activity. She writes about the various uses and displays of MySpace that teens employed to give their imagined audiences their desired portrayal of themselves. All of the featured adolescents rigidly adhered their profiles to a specific intention. Some wanted to follow the trends of the “in-group” popular students by posting content relevant to those groups and updating frequently. Others really only used it for its practical, communicative affordance to chat with their friends. Some used it to document their interests or as a creative outlet. Regardless of what stance their profiles took, they all had an intended purpose, an imagined audience, and a set of restrictions and freedoms that worked in those contexts (see “Authentic Writing” in Educational Applications). Students’ engagement in navigating these media is thus revealed to be not only social, but self-reflective as well.

Students, both online and in-person, are required to navigate social contexts. How they choose to participate in these contexts informs their presentation of self. boyd writes, “The mere act of creating a profile on a social network site requires some self-reflection” (boyd 129). Students choose which features of themselves to present and which to cast off in order to best align with the constraints of the contexts and publics they participate in. While boyd investigates the connections between social media profiles and “bedroom culture,” she points out that bedroom self-representations and “virtual bedrooms” differ in the “scale of the audience” (138). There is a restrictive element of virtual profiles beheld in the nature of the imagined audience and what it is perceived that they want and do not want to see.

As such, a prevalent sense of performance and presentation associated with a profile online is created. Students have to navigate how they want to be perceived not just in their profile, but by their audience. What aspects of their “bedroom” they want to share and those they want to keep private. Thus, how students orient and showcase themselves online speaks to skills educators want them to hone within the classroom. In addition, the nature of relationships explored with social media is relevant to those of literature. Just like social media users engage with their audience, both imagined and realized, so does literature. Social media and literature teach “the ability to forge relationships between individuals and  within communities; the ability to communicate, collaborate, and share ideas within these communities; and the organic, egalitarian nature of the ideas themselves” (Klein 58). Social media creates connections in networked publics that enable students to communicate with other users, networked spaces like hashtags, and their own digitized bodies. The communities established in social media hinge on collaboration and participation to maintain the activity of those communities. Once a hashtag or space becomes inactive, the community almost entirely ceases to exist. By fostering an active community based on communication and collaboration, social media emerges as a potential outlet for educational practices.

within communities; the ability to communicate, collaborate, and share ideas within these communities; and the organic, egalitarian nature of the ideas themselves” (Klein 58). Social media creates connections in networked publics that enable students to communicate with other users, networked spaces like hashtags, and their own digitized bodies. The communities established in social media hinge on collaboration and participation to maintain the activity of those communities. Once a hashtag or space becomes inactive, the community almost entirely ceases to exist. By fostering an active community based on communication and collaboration, social media emerges as a potential outlet for educational practices.

Back to Final Project Homepage