Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part blog series on choosing the right technology for your teaching needs. In this blog post, Associate Professor of Mathematics, Moira Chas, discusses her experience with finding a way to engage her students during synchronous online lectures. Look for the second blog post by CELT Instructional Designer and Technologist, Jennifer Jaiswal, who will describe how to select the appropriate technology. Email CELT@stonybroook.edu to get a consultation with an instructional designer who can work with you to choose the right tools for your teaching goals.

Moira Chas, Associate Professor, Mathematics

Moira Chas, Associate Professor, Mathematics

Image courtesy of Moira Chas, who is seen in her office with some of the crocheted models she has created to illustrate ideas in topology.

Before the terrible pandemic that turned our worlds upside-down and inside-out, (or better said, outside-in), I used to teach by walking incessantly around the classroom, asking many questions and trying to read in the faces of the students whether they had arrived at the answers. I peeked at the pages they were writing, and if I found cell phones on desks I would point out how unproductive these gadgets can make us. I often brought to the classroom as many “math toys” as possible to make mathematical ideas tangible.

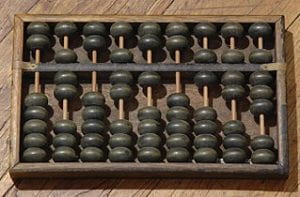

I remember the last class I taught in person in March 2020: It was about Mathematics in Ancient China. (I was teaching a course in History of Mathematics.) I distributed a few abaci and advised the students not to share them. (It felt terrible to have to recommend such a thing. Normally, I would have them working in groups with all hands on the abacus). The week after, we entered the Zoom-universe. It was hard to lecture there, but at least I was talking to students with whom I had established a connection before becoming a face on their screens.

The next semester, for reasons that I will spare you, I decided to be a virtual instructor. A significant challenge I experienced was in replicating the immediate interaction of physically being in the same room with my students as they solved problems. I needed a tool that would allow me to conduct polls and to pose open-ended questions in real time while I conducted synchronous online lectures for my courses, which typically have an enrollment of 35 students.

I investigated several platforms, including Slido, Mentimeter, TurningPoint, and Poll Everywhere. In all these platforms, students can type written answers to questions through a web browser. Instructors can see the answers and share them, if they so desire, with the whole class during a synchronous online meeting.

Stony Brook University supports the use of TurningPoint, where each student pays a fee for a license. Currently, the cost is about $10 for a five-month term. One benefit of using TurningPoint is that the student responses can be connected to the Grade Center in Blackboard. For options that result in no extra cost to students, Stony Brook instructors can use Google Forms, but I found this a bit “less interactive.” Google Docs and Google Slides are platforms where students write in a “live” document (In Slides, the instructor can prepare a set of identical slides and assign a group of students to each slide for a problem-solving activity in real time). Zoom also has a polling tool that instructors can use for real time interaction during a meeting. Lastly, Zoom has the chat tool, which also allows for immediate interactivity during a synchronous meeting.

After exploring all the options, I decided to pay for my own subscription to Poll Everywhere. This tool helped me simulate the real time human interaction of being in the same physical space with students. In fact, this tool proved so valuable that I am planning to keep using it after the pandemic is behind us.

This is how I used it. When teaching during a synchronous meeting, I started a typical lesson with a greeting and a word cloud that was generated by the students’ answers to a question like, “write down a word that describes how you feel”, or “tell us something you gained and something you lost because of COVID” I tried to acknowledge the hardship of the moment and, to remind us of hope.

During the rest of the lecture I would never talk for more than 10 minutes without having the students participate in some way. For instance, when we studied how Ancient Egyptians measured geometric figures, I asked students to answer one of the following questions: “What does measuring a segment mean?” or “How do you measure a segment?” At that point in the course, Egyptians were discovering mathematical concepts and I wanted my student to put themselves in the experience of discovery. After reading some answers, I gave my own, or shared some of the students’ responses. I explained why certain answers were inappropriate. Then I asked, “What does it mean to find the area of a plane shape?” Finally, I gave concrete examples of Ancient Egyptian problems where shapes are measured.

Another frequent activity was having the students read a paragraph and explain what it means. For instance, it is said that when the ruler Ptolemy asked Euclid whether there was a way of learning geometry faster than reading The Elements, a 13-book mathematical treatise, Euclid answered: “There is no royal road to geometry.” Then I asked students to write what they thought Euclid meant.

Sometimes I asked for educated guesses on topics where students were unlikely to know the answer. After a discussion, I would pose the same question again. I tried to use Zoom breakout rooms for group activities, but I did not manage to do it in a productive way. I would often visit a breakout room and find the students in complete silence. Some students expressed frustration at the lack of participation by their classmates.

Every time a beautiful math idea appeared in front of us (and there are so many!) I would point it out and emphasize how lucky we were to be studying such wonders.

At the end of each lecture, students wrote up a short summary of the lecture and submitted it through the Poll Everywhere tool. However, this could be done with another tool or through Blackboard, which is the learning management system supported by Stony Brook University.

Overall, I think all of us learned about math history and about each other. Reading the students’ answers to my open-ended questions was like visiting their minds, in a way sometimes more effective than my “face reading” during the in-person lectures. Mostly because I could read the answers one by one, (and when reading a whole bunch of faces it is easy to miss a few), and also because all students answered (and words are often more explicit than faces).

Two books have helped, taught, and inspired me during this time of teaching during the pandemic: James M. Lang’s Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning and Dan Levy’s Teaching Effectively with Zoom: A Practical Guide to Engage Your Students and Help Them Learn. Lang has also many useful essays in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

While I write these last words, the students of last semester come to my mind, and I find it hard to believe that I miss them even though I never met most of them in person. This was my first all-virtual teaching semester, and despite all the turmoil of the time we are living in, to my surprise, I enjoyed almost every minute of the experience.

Dr. Chas and Dr. Alan Kim are facilitating the SBU Faculty Writing Group, which meets on Fridays from 1:30 to 2:30 p.m. starting on Feb. 5 through April 30, 2021. Register at this link. The Faculty Writing Group is sponsored and supported by the CELT’s Faculty Commons.