In my previous post, Being Blue in New York, I sketched out a brief history of cholera in New York City and the development of disease theory and of prevention and management strategies over the course of several outbreaks. Today I am going to talk about quarantine, class, and immigration.

Prevention and management of epidemics was the responsibility of the New York Board of Health, a committee established in 1805 in the midst of a series of Yellow Fever outbreaks. The Board of Health was formed out of a recognized need to “establish greater authority over local sanitation to control Yellow Fever” and future heath crises. Their response to cholera was just as halting and inconsistent as it had been for previous Yellow Fever outbreaks; a disastrous combination of understaffing, underfunding, inaction, incompetence, politics, and stigmatization of immigrants is responsible for inconsistent and unsuccessful action. The committee experienced changes over the years, becoming less politically aligned with the gradual inclusion of physicians into their ranks. The Department of Health, the reincarnation of the Board of Health, has thankfully continued to develop from this stumbling adolescent stage into a capable organization that is currently helping to manage the Covid-19 pandemic.

As the disease spread across Europe in 1831 the Board tried to contain cholera to quarantined ships, but “once cholera cases began to appear in the city, the Board was slow to recognize them, as cholera would interrupt the flow of commerce.” In 1849, when the Board’s plan to set up quarantine hospitals were under fire from hostile landlords, they had to adapt and converted “the second floor of a tavern and four public schools as a makeshift facility.” The Board would gradually gain power and influence over the course of the nineteenth century and by 1892 it was a proactive organization which had begun to collect the resources necessary to guard against epidemics. Through the efforts of the Board of Health and reform-minded citizens New York City avoided the cholera epidemic that was sweeping Northern Europe in 1892 because of cleaner streets, access to uncontaminated water, and nondiscriminatory quarantine measures. I will explain what I mean.

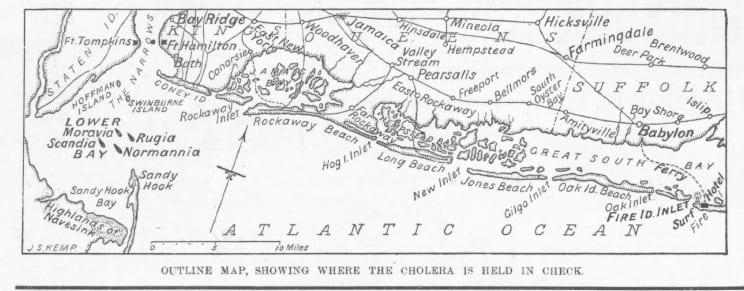

I am talking about the quarantine of the 1892 Port of New York, an affair managed by Dr. William Jenkins. In August vessels contaminated with cholera began crossing the ocean from Hamburg to New York. From August to October “76 passengers died en route to New York, and another 44 deaths occurred among the immigrants quarantined at Swinburne Island.” New York City only had ten deaths related to cholera. Considering the devastation the disease had wrought in the past it seems as though quarantine was very a very effective measure and had prevented disaster in New York. However, this strict state sanctioned quarantine became a scandalous affair when affluent Europeans and wealthy Americans returning from summering abroad had to be detained along with the immigrants in steerage.

In 1892 Dr. Jenkins was a “Health Officer of the Port of New York and chief of the Quarantine Station.” Jenkins was ill-prepared for the influx of contaminated voyagers, having on staff only “two experienced physician-inspectors… two inexperienced ones he had hired five days earlier… two doctors… two disinfectors, ten nurses, and a number of aides and laborers.” Jenkins lacked the resources to properly manage the containment of the “997 vessels, 80,777 passengers, and thousands of tons of baggage and cargo” that would need to be inspected, treated, and disinfected.

As the hospitals and islands reserved for immigrants were overcrowded Jenkins needed to secure more accommodations, specifically for the cabin class of the Normannia, who had been confined to their ship for days and had begun to air their discontent and the horrors of their inhumane treatment to the eager press boats circling the harbor.

I would like to share a passage from Howard Markel’s article, “‘Knocking out the Cholera’: Cholera, Class, and Quarantines in New York City, 1892,” because it is very informing:

From his first-class stateroom aboard the Normannia, [E. L.] Godkin composed a series of castigating articles entitled “Letters from the Normannia,” which were published in newspapers across the country. In one ‘letter’ Godkin accused Jenkins of fabricating a diagnosis of cholera among the cabin passengers as a means of asserting his power. In another dispatch, he charged Jenkins with failing to provide adequate food, water, and medical care, and with neglecting to remove dead bodies from the ships for periods exceeding twenty-four hours. Perhaps an excellent example of the myopia that accompanies days of isolation in quarantine was the deterioration of Godkin’s complaints, as the days and weeks in quarantine progressed, from public health issues to the ‘wretched table service’ aboard the ship.

Other cabin passengers of the Normannia were just as vocal about their suffering, and just as insensitive to the immigrants crammed in steerage confined among the sick with far less comfort, amenities, and personal space than those confined to their cabins.

When it became clear that cholera may be among the cabin passengers Jenkins made the unpopular decision to quarantine the wealthy as well (before the discovery of the disease on the ship the cabin classes were going to be released while the steerage passengers were going to be contained and disinfected), though with special accommodations. The affluent would be quarantined at the Surf Hotel on Fire Island.

What we see happening during this quarantine is the fracturing of the healthcare system along class (rich and poor), status (tourist and immigrant), and nationality (American and foreign) lines. Over the course of my research I have found that there was more to the story of the Cephus than a standoff between locals and an infected ship. The story I will be telling you is about class, status, and nationality. The Long Islanders who prevented the docking of the Cephuswere protesting against an overreach in state over local authority. They did not care about the status of the passengers. All they wanted was to protect their land and livelihoods from disease and immigrants. This is a very interesting story that I will be sharing with you.

Further Reading:

NYC.gov

“Protecting Public Health in New York City: 200 Years of Leadership, 1805 – 2005” by Marian Moser Jones

Howard Markel “‘Knocking out the Cholera’: Cholera, Class, and Quarantines in New York City, 1892”