Stores had “Business as usual” signs on their windows, but life was hardly “as usual” in London during the Blitz. Beginning in September 1940, German bombs fell on London at night. For their safety, millions of children from the capital were sent away to live with family, friends, or volunteers in the countryside. For those who stayed in London, life changed dramatically. London’s East End was hit particularly hard, with many of the foreigners who lived there losing their lives and homes. Food and clothe rationing meant every piece of land was used to grow extra food and people were given “coupons” to obtain the clothes they needed. At end of the Blitz, over 40,00 people died and over a million left homeless.

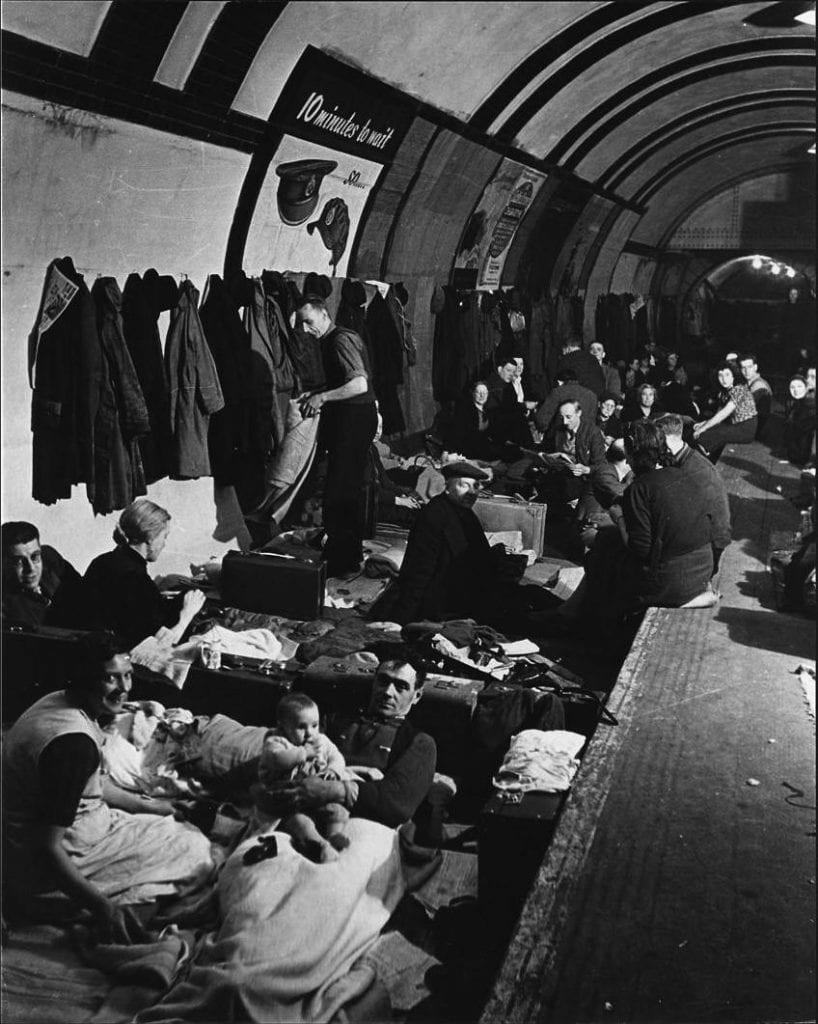

As the days during the Blitz dragged on, people repeated, “We shall get used to it.” Yet those in London had to continually deal with the horror of war. As the sun set in London, people hurried to their houses and allowed for the darkness to fill their homes. They did not turn on any sources of light to make it difficult for the German air force to locate strategic targets around the city. Once in their homes, Londoners waited for the sirens to go off, signaling that enemy bombers were approaching. They had to rush to air raid shelters: basements, subway tunnels, or bunkers. In the daytime, they would leave shelters hoping their homes would still be standing. For those whose houses were destroyed, they had no choice but to convert the metro stations into homes. In the beginning, the cold darkness, and echoes of explosions echoed filled these tunnels.

But people from different backgrounds congregated in the tunnels for the first time and found ways to obtain some ease from the discomforts of their situations and the terror up above. At its highest number, 150,000 people slept in the tunnels. Rather than descend into chaos, people began to create informal governments and committees. At times initiated by clergymen or air-raid wardens, these committees designated specific spaces for playing, sleeping, and smoking. Committees also served to resolve disputes or pressure the government for additional aid. Over 30 committees were established, and conferences were held amongst them to share ideas and strategies.

Although a government report referred to these committees as “communist in character,” the interclass solidarity that occurred also helped to escape from their realities and change social perceptions. Committees played music on speakers, put on dances and plays, established reading and sewing groups, and on Christmas Day put up decorations and threw holiday parties. The lives they built in these stations led to interactions between working class people with middle and upper classes. This exposure grew into relationships that soon shifted the perception of working-class people from degenerates to people with “dignity.”

Even though the Blitz had terrible consequences, historians point out that the one positive outcome was the unification it caused. People in London had more sense of unity than before. Their time living in close quarters and helping one another led to a stronger community that eased their experience during the Blitz.

Further Reading

“What Life Was Like During the London Blitz” by Livia Gershon.

“London’s forgotten network of massive underground air raid shelters is being found again” by Leo Hornak.

“Living Through the Blitz” by Mollie Panter-Downes.

Battle of Britain, “Life During the Blitz,” from rafbf.org.

“Children of Wartime Evacuation,” by Julie Summers.

“Nights Underground in Darkest London: The Blitz, 1940-1941,” by Geoffrey Field.