Today we will be looking at some forms of protest and dissent which colonial merchants and consumers engaged in, as well as some interesting incidents that followed. After the French and Indian War, or the Seven Years War as it was known globally, the British Parliament passed a series of acts imposing taxes and importation duties on food and material goods in an effort to pay for the war and future defense of the colonies. Years of inconsistent, unenforceable, and incomprehensible policies established a loose, laissez faire style of colonial governance that was very favorable to the colonies. Many in the economic, merchant, and supply occupations prospered and contributed, through their trades, to the relatively higher quality of life and opportunities in the colonies as a whole. As a result, a majority of the colonists were resentful of the efforts of such men as the British Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend to reassert imperial control over the economy and governance of the colonies. So, how did colonists voice their discontent with imperial policy? Let’s get into it.

Smuggling was a tried and true tactic employed by provincial merchants to engage in trade with foreign powers, even during war, and to avoid import duties. Smuggling itself is a form of protest, in which the merchant rejects restrictions in order to trade freely and profitably. Smuggling was a near treasonous offense because, in the act of exchanging New York flour for French Caribbean rum New York smugglers were supplying the French army with desperately needed provisions at the expense of British troops and prolonging the war.

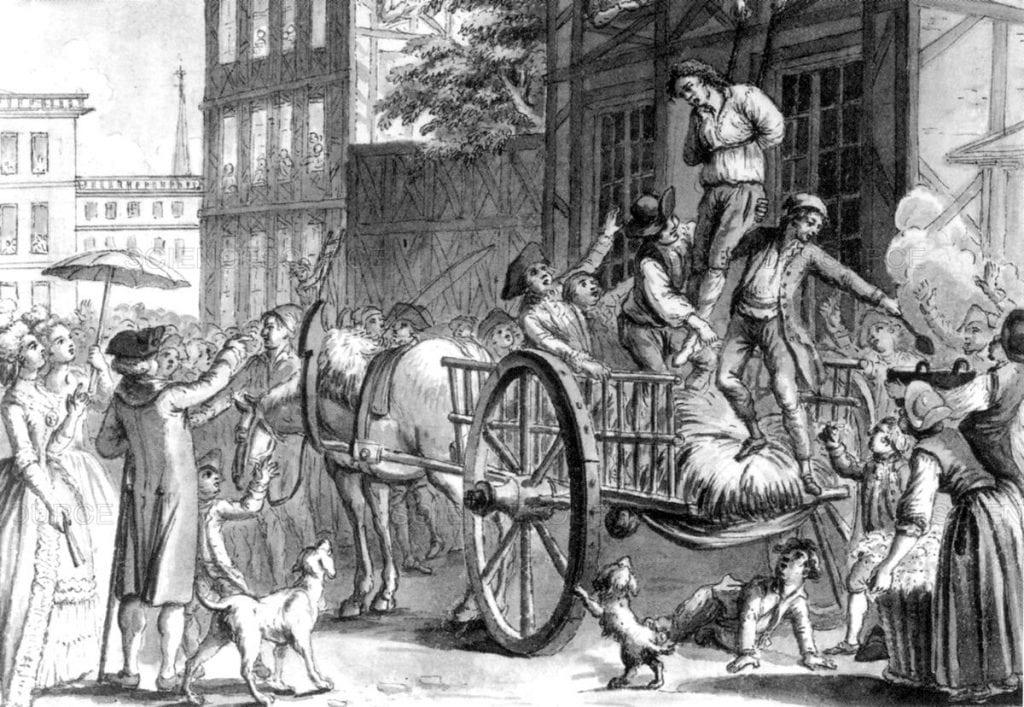

Pressured by Major-General Jeffery Amherst, Archibald Kennedy (the collector of customs for the port of New York) made two appeals to the public asking for information on “the landing of any foreign rum, sugar, or molasses, within this district, before entry made, and the duties paid” in exchange for “one full third part of the whole, with the thanks, doubtless, of his country” once the guilty smuggler and their employer had been condemned and charges deducted from the illicit cargo. No one came forward because many of the city’s more prominent and influential merchants and city officials were involved either directly or through connections in the wartime smuggling with France. In October of 1759 after the second appeal George Spencer, a struggling wine merchant, reported his discovery of “five or six vessels in the harbor” waiting to pass through with false papers and smuggled cargo from Hispaniola to Lieutenant-Governor DeLancy and Archibold Kennedy. Unfortunately for Spencer, both men were personally invested in the wartime trade. Word quickly got out that there was an informer at large.

New York had profited immensely from wartime contraband, from the merchants, to the sailors, to the officials paid for their cooperation and silence. Spencer’s knowledge and his persistence presented a direct threat if he informed a royal official whose interests did not align with the illegal trade. A plot was immediately hatched between a dozen men, mostly merchants concerned in the exposure of the illegal trade, to humiliate and discredit Spencer and intimidate into silence any future informants. Manhattan’s merchants went to great lengths to protect their smuggling trade. Spencer, instead of reviving his fortunes from the informer’s bounty, was threatened, carted through the city by a mob of routy sailors and pelted with clubs and garbage, arrested three times, imprisoned twice, and sued at least twice. If Spencer felt that “he was at war with the city of New York” he very well may have been, because there were many people involved in the smuggling trade in one capacity or another, including in their ranks politicians, royal officials, merchants, and sailors. Those involved certainly went to great lengths to protect their trade from imperial policy. Reaction and retribution could be swift. Let’s turn our attention to other forms of protest, ones which engaged a much larger population than the city merchants and their accomplices.

One cannot talk about colonial era protests and not mention consumer protest movements. In my experience it was the consumer protests that I first learned about in elementary school, protests against unjust taxes on stamps and tea, that informed my first impressions of American liberty and freedom of expression. The consumer response to the infamous Townshend Acts and other like laws that taxed or placed import duties on widely consumed products and goods is very interesting to me now because of the scale and intensity of the various isolated protests and the gradual development of a collective colonial response. Also, tea is my go to drink for reading, writing, and my cure-all for any malady. I would have had a very difficult time switching from Tory tea to Patriot coffee.

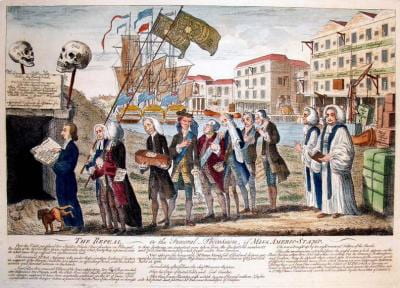

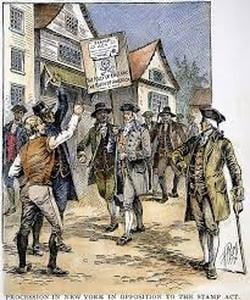

The Acts placed taxes or import duties on essential products such as paper, common fare such as tea, and luxury goods such as sugar. So many people were impacted by the Acts because virtually every person consumed these products either directly or indirectly. Consumer protests turned taxation into a politicized issue because the products they meant to tax became objects or symbols of imperial oppression. Colonists protested the Acts through various methods as individuals, households, communities, and mobs. Such methods of protest included: boycotts, petitions, production of homemade garments and products, seeking out American or foreign substitutes, and vandalization, humiliation, and intimidation of merchants and consumers caught with the offensive products usually through violence and hangings in effigy. Should all other acts of protest fail the offensive products were sought out and destroyed by vigilantes, mobs, or appointed committees.

One very interesting consequence of the Townshend Acts was the development of “a highly charged moral language” and “public virtue” expressed through a condemnation of extravagance and weakness of character. Between 1767 and 1770 consumer products were imbued with political and moral meaning. As T. H. Breen explains, “By acquiring needless British imports the colonial consumer threatened the liberties of other men and women.” Tensions grew so high that on March 5, 1770, the same day that British Soldiers were provoked into shooting at a crowd in Boston, the Prime Minister Lord North asked Parliament to repeal the Townshend Acts. The tax on tea remained.

On December 16, 1773 members of the Sons of Liberty gathered after dark, disguised themselves as Native Americans, and disposed of 342 chests of British East India Company tea in the Boston Harbor. The Boston Tea Party and the Intolerable Acts placed on Massachusetts following the protest sparked similar acts across the colonies. Following the Intolerable Acts, the selling, purchase, and drinking of tea became synonymous with compliance and treason against the colonies and revolutionary sentiments were steadily gaining traction. In December of 1774 a shipment of tea arrived in Greenwich New Jersey and was secured in Daniel Bowen’s basement. In response to this discovery local resident Philip Vickers Fithian reported that “A pro Tempore Committee was Chosen to Secure it till the County Committee be duly elected” to deal with the offensive product. The problem was resolved before either committee could act. On the night of the 22nd “the Tea was, by a number of persons in disguise [as Native Americans], taken out of the House & consumed with fire” in the town’s market square. Their actions are remembered as the Greenwich Tea Burning.

Further Reading:

- Defying Empire by Thomas M. Truxes

- Merchants & Empire: Trading in Colonial New Yorkby Cathy Matson

- “‘Baubles of Britain’: The American and Consumer Revolutions of the Eighteenth Century” by T. H. Breen

- Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America by Linda Kerber

- https://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/townshend-acts

- https://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/boston-tea-party

- The Way of Improvement Leads Home: Philip Vickers Fithian and the Rural Enlightenment in Early America by John Fea