Colonists used the belief of witchcraft to grapple with psychological tensions and concerns that had developed out of trying to make sense of their new external worlds, ultimately embedding witchcraft into the cultural belief system of the United States. In England, the Church suppressed any voice or power women may have had by limiting their societal roles. On the other hand, the Puritans believed that men and women were “equal” in the eyes of God. When arriving to the new settlements, Colonists needed to rely on both men and women to do their designated roles faithfully. This was to ensure the success and stability of their communities. Accusations of women practicing witchcraft in New England came about because the strict moral doctrine that Puritans adhered to created gendered societal roles and fear concerning the inability to attain salvation.

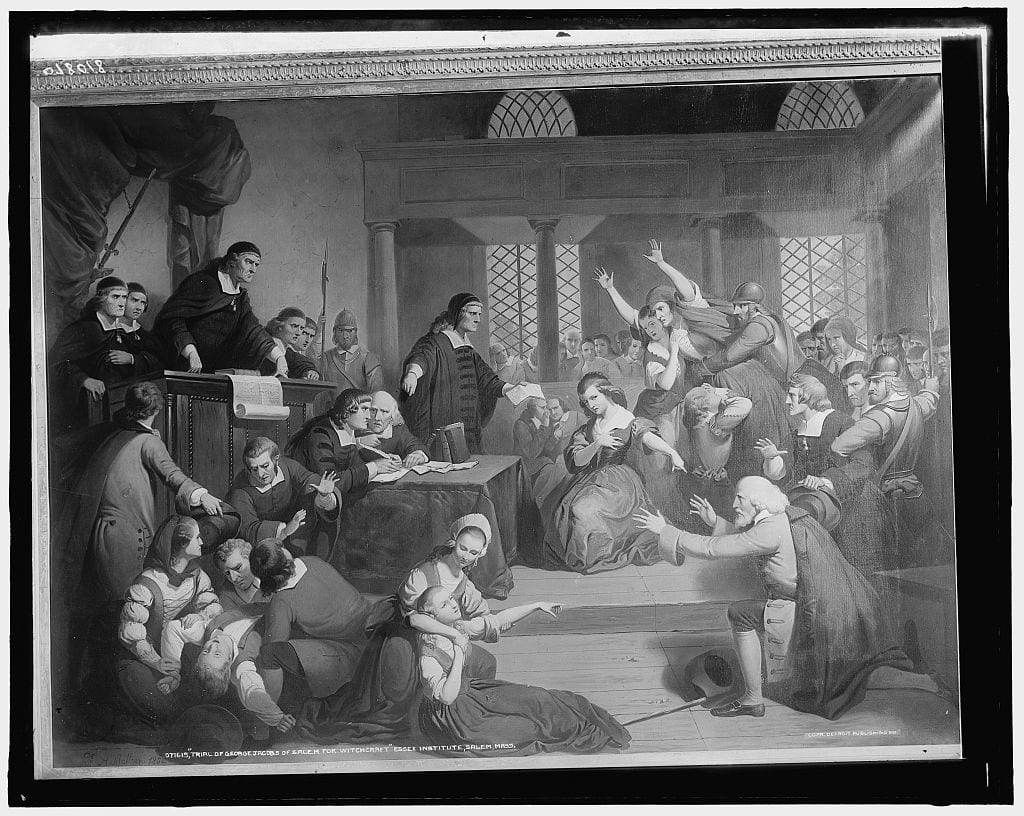

Men and women worked together to ensure the success of their communities. Women were afforded more of a presence in ecclesiastical and secular affairs, but their actual voices were still suppressed because of the paternalistic nature of New England society. Accusations of witchcraft being associated with discontent and anger in women specifically reflected gender relationships through pastors preaching about the association of women with “religious dissent” (see Figure 1). Carol F. Karlsen states in her book, Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England, that religious doctrine in Puritan society shaped their values in everything revolving around daily life. Their doctrine sermonized that witches had challenged God’s supremacy since they worked advertently against the “prescribed gender arrangements” of their society. Since God assigned gendered arrangements, these two offenses were indescribably linked. By preaching this, ministers were able to check the newly gained powers women had shortly attained in living in an egalitarian society. The congregation viewed specifically widows’, or really any woman who was vocal in community affairs, noncompliance as not merely “un-neighborly”, but as evidence of witchcraft itself. Especially since church officials had termed a sign of witchcraft being a “woman’s refusal to accept their “place” in New England’s social order”, and an exhibit of outward anger. For this reason, women were to be the targets of domestic quarrels that were then later used as evidence for witchcraft during trials because in these disputes they also acted with discontent and anger through maleficium.

The fear of witchcraft did not end with the devastating events that had unfolded in Salem, but actually continued well into the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries with the Ozarks. Ethnographer Vance Randolph recorded the oral histories of the Ozarks in extensive detail. While reading his text, Ozark Witchcraft, many parallels can be made between the Puritans’ and Ozarks’ beliefs in witchcraft. According to Randolph, the Ozarks believed that women specifically made pacts with the Devil by going to the cemetery late at night and giving the Devil her “body and soul”. Similarly, Puritan preachers and other appointed congregation members would question the accused witches of making a pacts with the Devil, like in the case of the examination of Sarah Good where Hathorne questioned on her this matter. Randolph then discusses how locals told him of certain “forms” a witch preferred to take. He states, “A witch can assume the form of any bird or animal, but cats and wolves seem to be her favorite disguises”. While in Salem, John Lauder had accused Bridget Bishop of sending her monkey familiar to his window to send him a message from the Devil. Lastly, Randolph recalls a few stories where community members had broken out into fits and had expressed aversion towards religion after having a dispute at the market or in bartering with fellow community members. This specifically parallels the same psychological distress in Salem in the case made by Samuel and Sarah Shattuck against Bridget Bishop. The Shattuck’s claimed that after a dispute with Bishop over an animal, their once vigorous older son’s health declined. He would also break out into fits at the sight of Bishop. The Ozarks are but just one example of witchcraft surviving post- Colonial New England.

Contemporarily, in Fourth Wave Feminism (specifically in the West/United States) people of all genders are now reclaiming witchcraft as a means of empowerment and liberation in retaliation of suppressive socio-economic practices. This is in complete reversal of witchcraft’s origins in the history of the United States. That’s not to say though that others throughout the world today are not being falsely accused for witchcraft and executed for their beliefs or behaviors like those had in medieval Europe and Colonial New England. While others in the world are still fighting false allegations, other activists are transforming the witch archetype to integrate intersectionality and combat gender binaries in our society today. Estelle Freedman states that “…feminism has passed the historical test of time, largely because it has redefined itself in response to a variety of local and global politics…(and) has survived only through multiple, complex responses to economic and political change, through adaptation to diverse cultural settings, and through incremental shifts in popular thought.” The same can be said of witchcraft. In the United States, accusations of witchcraft were originally used by early settlers as a scapegoat and a form of suppression against outspoken women; today it has been reclaimed as an archetype of power for those who are often marginalized by society.

Sources and Further Readings:

Carol F. Karlsen, “Handmaidens of the Devil”, in Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998), 117-131.

Estelle Freedman, No Turning Back:

Examination of Sarah Good, March 1, 1692, 69. . (Primary Source)

John Louder Against Bridget Bishop, June 2, 1692, 112-13. . (Primary Source)

Kristen Sollée, Witches, Sluts, Feminists (Berkeley: ThreeL Media, 2017), 8-19.

Richard Tomczak, “Gender in New England and the Hartford Hunt, 1630-1680,” Lecture, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, June 1, 2020.

Samuel Shattuck and Sarah Shattuck against Bridget Bishop, June 2, 1692, 114. (Primary Source)

Vance Randolph, “Ozark Witchcraft,” in Ozark Magic and Folklore, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1964): 267-71.