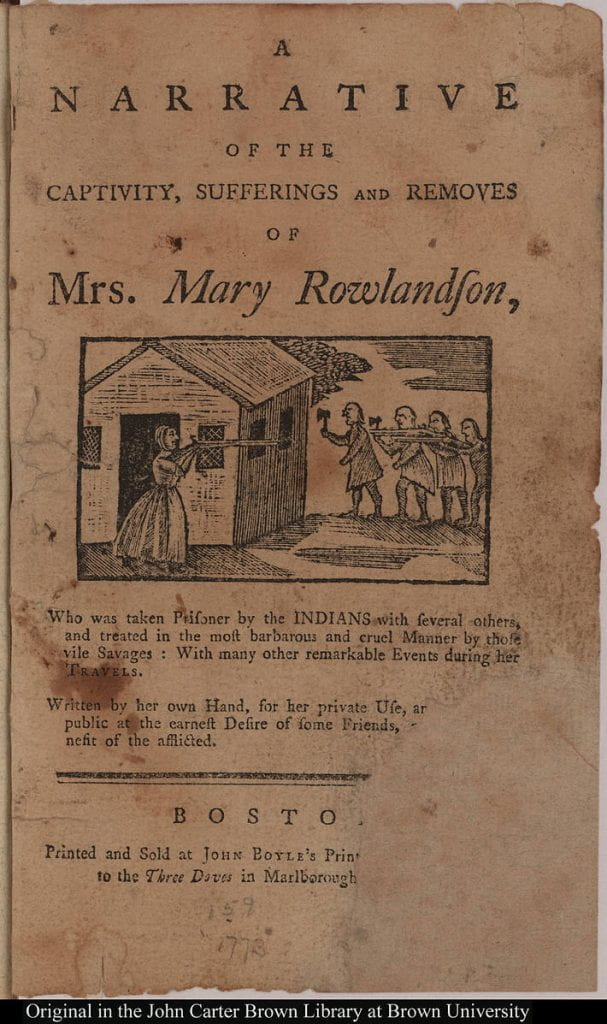

This image of the title page is from one of the surviving 1682 editions of A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson. Mrs. Rowlandson was taken captive during a raid on Lancaster, Massachusetts during King Philip’s War; a war initiated by Metacom (Philip was his english name), sachem of the Wampanoag tribe, over strained relationships with New English settlers and encroachments on their lands and sovereignty. Other regional tribes joined as allies of Metacom or independently as enemies of the New English settlers. Mrs. Rowlandson and about twenty other survivors, mostly women and young children, were taken in what Native cultures called a Mourning War, in which captives were taken from neighboring or hostile people and gradually incorporated into the captors tribal unit to replace loved ones and replenish the population. The bloody nature of the Lancaster raid can be attributed to deep seated hostilities between the Invasive and Native populations. Many English captives were returned; those that were not had been assimilated or died. Most Native captives were not so lucky. Most were killed before they could be taken, others fled to neighboring tribes; those that were not dead and could not flee were sold into regional or foreign slavery, usually to the Caribbean sugar islands. Christian Indians, Native people who had adopted Protestantism and the English language, were usually exiled to Praying towns or reservations.

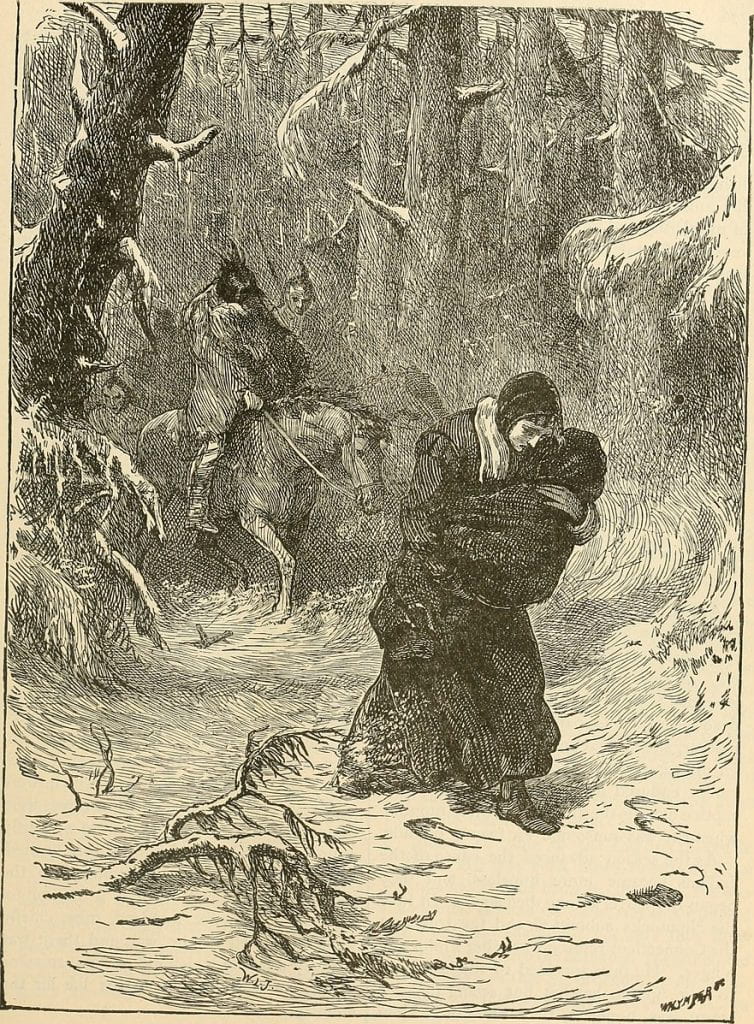

Illustration, Mrs. Rowlandson Captured by the Indians, from Our greater country; being a standard history of the United States from the discovery of the American continent to the present time, by Henry Davenport Northrop, 1901.

Captivity narratives were very popular for a long time, and Mrs. Rowlandsons’s was one of the most enduring According to data collected by Kathryn Zabelle Derounian, Mrs. Rowlandson’s account of her captivity was “[o]ne of the first American best sellers with an estimated minimum sale of 1,000” and four editions from Boston to London in 1682, its first year of publication. I imagine that captivity narratives were popular for the same reasons that plague or pandemic movies are, or were (personally, after living through one I will never be able to watch another again). While there were certainly embellished or fictitious accounts, most captivity narratives were based on the experiences of the authors. These were Puritain sensationalist reality dramas, an avenue through which the reader could safely entertain and then dismiss the scandalous connotations of a Protestant female held captive by “heathen” Native people. Mrs. Rowlandson’s narrative follows a pattern of confirmation of English Protestantism against a demonic and corrupting Other and is as much an affirmation of her own culture and condemnation of the culture of the various Algonquian speaking tribes of the region. The particular way she expressed her understanding of her experience was through trial, or affliction, and redemption through unwavering faith in God’s divine plan and acceptance of His will. She never tried to escape her captors because of her conviction that only God’s will could save her, in body and soul. “[T]he Lord renewed my strength still, and carry’d me along, that I might ഽee more of his power, yea ഽo much that I could never have thought of it, had I not experienced it.” After eleven weeks, five days, and £20, she was returned to English society, her husband, and eventually her two surviving children. Her narrative was published six years later.

We do not know what illustrations the original editions had, if any, because so few of the pages survive. However, I found some very interesting illustrations from the 1770’s editions that beg explanation, or at least discussion.

Mary Rowlandson never mentioned having a gun and she condemned violence. How is it that we have two illustrations of an armed woman in her narrative? Who is this woman if she is not Mrs. Rowlandson? I believe these women were symbols, though there are many different things that they could stand for. The woman in this first image is defending her home from armed men, some with hatchets and others with muskets wearing long coats. Jill Lepore proposes that these figures are Red Coats, British soldiers. Their presence in the title page for this narrative is meant to harken back to the terrors of King Philip’s war a century ago and rekindle fear of a malicious and foreign Other. In the revolutionary mind, Red Coats replace Indians as the threatening force against their society and livelihoods as the British are refashioned into a people different from and hostile to the American colonists.

Illustration from A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson. 1770 edition.

What about the second image? Here we see a woman standing with a rifle, a powderhorn in hand, and a tricorn hat on her head. There is more to say about her, because this is not the first or the last place she has appeared. This same illustration was used in a children’s book in 1762 to represent Miss Fanny’s Maid. Copyright laws were nonexistent and consequences for plagiarism unenforceable. As such there were several gun wielding woodcuts lying in colonial printing shops. She appears again, reproduced, not duplicated, in 1779 in a broadside by Molly Gutridge entitled “A New Touch on the Times: Well adapted to the distressing situation of every Seaport Town, by a DAUGHTER OF LIBERTY, living in MARBLEHEAD.” There is a consensus that, in the context of the revolutionary sentiments of the 1770’s, this figure of a rifle-wielding woman represents a Daughter of Liberty, a woman dedicated to the patriotic cause, though her role beyond that is up for debate. Let’s focus on the image from Mrs. Rowlandson’s narrative. The question is, was this image meant as a call to arms, a critique, a warning, or a satire? I have come across convincing arguments for all four.

To answer the first two we need to look at female patriotism. Who was the female patriot? Linda Kerber explains that men expected feminine patriots to be “completely passive” characterized by virtuous suffering, humility, and preservation of innocence. The female expectation was more active as women were urged to support themselves and their communities when the men could not. Patriotic women were expected to perform charity work for local dependents and soldiers, and to support non-importation movements through their own labors, and boycotts by refraining to purchase British imports. They were still expected to preform their domestic duties and provide for their families despite wartime hardships and shortages. Should a local merchant hoard his wares or charge unreasonably for necessities such as bread it was within the female patriot’s power to demand or take what she needed for her family, as many did. Their patriotic duties remained confined within an expanded domestic sphere. They were never asked to arm themselves, though some masqueraded as men so they could enlist. This figure, then, could have been a call to arms, the Daughter of Liberty calling men and women to their respective fields. She could also have been a critique to the men who failed to heed her call for action and aid.

In the context of the captivity narratives she could also represent a warning. Caroline Light suggests that “[e]arly depictions of white women with guns were one part proxy, one part propaganda. An armed white woman might safeguard the home in her husband’s absence, but her image also triggered fear in the minds of Anglo settler defenders of white property.” “White property” can mean a few things, but for our discussion the term refers to land and the female body. In the Anglo settler’s mind, Native American masculinity represented a threat to their claim to virgin land and women.

Finally, there is the possibility that the rifle-wielding woman is a satirical character, as her appearance as Miss Fanny’s Maid would indicate. A woman masquerading as a man, an impossibility (especially since such female fighters never wore women’s clothing in the field). Should this happen it would truly be a “world turn’d upside down.”

What I think is most likely is that this figure was a stock image in the colonial imagination, one whose function changed with the context in which she was placed.

Further Reading:

- A Narrative of the Captivity, Sufferings, and Removes, of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson by Mary White Rowlandson

- The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity by Jill Lepore

- Women of the Republic: Intellect & Ideology in Revolutionary America by Linda K. Kerber

- “The Publication, Promotion, and Distribution of Mary Rowlandson’s Indian Captivity Narrative in the Seventeenth Century” by Kathryn Zabelle Derounian

- “Women and the American Revolution” by Wendy Martin

- “Guns Were for White Men” by Caroline E. Light

- “Tracking Down a Mustek-Toting Woman” by J. L. Bell

- “A New Touch on the Times: Well adapted to the distressing situation of every Seaport Town By a DAUGHTER of LIBERTY, living in MARBLEHEAD” by Molly Gutridge, Broadside, 1776, Massachusetts