What Spirit Photography can tell us about the Science behind Spiritualism and the Act of Mourning

[Unidentified elderly woman seated, three “spirits” in the background]; William H. Mumler (American, 1832 – 1884); 1862–1875; Albumen silver print; The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

William Mumler reportedly took the first spirit photograph in a Boston studio he shared with his wife Hannah in 1862. Hannah, prior to meeting her husband, was in the business of post-mortem hair braiding, photography, and mediumship. The first spirit photograph was a self portrait. Mumler was alone when he took the picture, but in the dark room a second, ghostly form appeared on the glass behind him. It was a little girl, who he eventually identified as a cousin who died years before.

At the time of their development, these photographs provided empirical evidence of an afterlife for the faithful and a reunion between mourners and their loved ones. To skeptics, the images represented instead a deception, fraud, and delusion. 160 years removed from their original context, these images take on new meaning. To the modern gaze they are a curiosity or a window into the past. Setting aside any questions of religious truth or secular deception, the art of spirit photography is nonetheless fascinating and haunting for what it can tell us about the times in which people lived and how they grieved. This perpetual ability to construct meaning is what Louis Kaplan calls “the affective power” of an object or media.

To borrow a phrase from Alex Owen, “I do not and cannot make a final judgment on the reality or otherwise of the spirits.” My purpose here is to share these photographs and the glimpse they give us into the fascinating period that brought the dead to life.(1)

Mumler’s spirit photographs were fakes. He was exposed several times for recycling old negatives from his wifes collection and passing off the living as the dead. The authenticity of Mumler’s photographs was tested by skeptics throughout his career and by the courts in 1869. In May of that year, Mumler was acquitted on all counts of purposeful fraud. On May 8th, Harper’s Weekly: Journal of Civilization remarked on the case:

If there is a trick in Mr. Mumler’s process it has certainly not been detected as yet. To all appearances spiritual photography rests just where the rappings and table-turnings have rested for some years. Those who believe in it at all will respect no opposing arguments, and disbelievers will reject every favorable hypothesis or explanation. (2)

Exactly how Mumler produced these double exposures under the observation of the professionals remains a mystery to this day. Two things above all others helped Mumler win the case and salvage his reputation: opportune timing and expert marketing.

The “rappings and table-turnings” that Harper’s Weekly refers to were common modes of communication between the living and the dead. Spiritualism emerged in the late 1840s and thrived as a transatlantic religious and social movement into the 1890s. Every account of the beginnings of the movement involves the same core characters. Andrew Jackson Davis, a self proclaimed seer, built the framework of spiritualism from the ideologies of Franz Anton Mesmer and Emanuel Swedenborg. One of the core tenets of Victorian Spiritualism was that the dead could communicate with the living through a medium. In 1848, sisters Kate and Maggie Fox discovered that they could communicate with the spirit of a dead peddler in their home through a series of raps and knocks, setting the precedent for the movement and, with the help of sympathetic patrons, bringing it into the mainstream.(3)

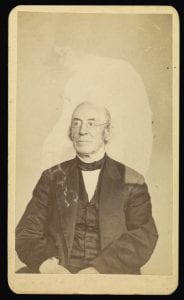

Famous individuals also got their photographs taken, and mediums would sometimes pose with their spirit guides. Not every spirit was immediately recognized, sometimes they never were. For example, see the following photograph of prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison:

William H. Mumler (American, 1832 – 1884)

[William Lloyd Garrison], 1869–1878, Albumen silver print

9.5 × 5.7 cm (3 3/4 × 2 1/4 in.), 84.XD.760.1.28

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Spiritualism was a movement based on the manifestation and investigation of empirical evidence of communication between the living and the dead in a period where the lines between science and pseudoscience were still forming. Spiritualists believed that their faith was founded in material evidence and observable phenomena, primarily séances. Skeptics thought the spiritualists, if not swindlers fueling a mass hallucination, were otherwise experiencing a psychotic delusion themselves. The movement emerged at an opportune time. Several forces came together to contribute to the strength and staying power of the movement, most notably the collective trauma of the American Civil War. As this is a post about spirit photography, let us turn our attention to the influence of technological breakthroughs in communication and the Victorian culture of mourning.

The nineteenth century experienced a revolution in communications technology that transformed how people understood time and space. The telegraph was invented in 1844, the first semi successful transatlantic cable was completed in 1858, and the first phone call was made in 1876. In the span of thirty years temporal and spatial boundaries were collapsing drastically, each new innovation making communication clearer and faster across greater distances. In such a climate of unprecedented transformation, it was not so unreasonable for people to believe they had communicated with people much, much farther than England. Spiritualism was inspired and, in the minds of believers, confirmed by apparent spiritual communications through these new media. Anthony Enns points out that the mechanical telegraph had its own spiritual counterpart. The method of communication was the same, but the medium was quite different.

In much the same way, as photography developed the technology was also enveloped into Spiritualism as visual confirmation of mostly audible phenomena. Mumler’s main line of defense during the trial was that the art of photography was still in its infancy, commercial photography having only just become feasible with new techniques like the daguerreotype and ambrotype processes. The photographer, using an alchemy of chemicals and darkness, captured an image created by light onto glass. The camera could seemingly see things beyond what humans could perceive.

For mourners and Spiritualists, the spirit photograph provided visual confirmation that the dead visited the living. The photographer was simultaneously an alchemist and a necromancer. Spiritualism placed agency in the spirits to communicate through a human or mechanical medium. Mumler himself was a novice photographer who claimed, credibly for some, to be a mere medium through which spirits decided to manifest. In proclaiming to be a medium, Mumler displaced his own agency by giving it to the spirits.

Photographs were quickly integrated into mourning practices as memorial relics. Bodily relics like locks of hair and teeth were static, frozen at the moment of death. Photographs like those supplied by Mumler and his peers appeared to animate the dead within their frames. This was a new kind of relic, similar to the hair ornaments Hannah Mumler made for her clients, “with faithful attention to the identity of the person furnished.”(4) Spirit photographs appeared to prove that mourners’ loved ones continued to exist in a state similar to our own.

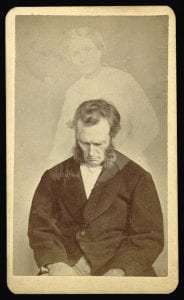

Bronson Murray, embraced by female “spirit” holding a cross.

William H. Mumler (American, 1832 – 1884)

Bronson Murray, 1869–1878, Albumen silver print

9.5 × 5.6 cm (3 3/4 × 2 3/16 in.), 84.XD.760.1.11

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

One of the most sensational testimonies of the Mumler trial, given by a “distinguished” Judge Edmonds testified that “I believe that the camera can take a photograph of a spirit, and I believe also that spirits have materiality – not that gross materiality that mortals possess, but still they are material enough to be visible to the human eye” and certainly material enough for a camera to capture.(5) The spirits had semi-corporeal forms, they wore drapes or clothing, sometimes they held props like wreaths and crosses. The dead chose to appear to their mourners, to stand beside them, and to embrace them.

The spirit photographs produced by Mumler and his peers became a dead commodity in a market for mourning relics. For $10 a piece, the equivalent of about 200 dollars today, the living could be reunited with their loved ones. At a glance, these photos mended a connection that had been severed. In these photos were reunions between parents, spouses, and siblings. Famous individuals also got their photographs taken, and sometimes a spirit guide posed with their medium.

Time has shifted the focus from the mourned to the mourner. While today we look at these images with curiosity and define them using theories of psychoanalysis, in a different time the focus was on the spirit. Believers saw in them empirical evidence of spiritual agency, an affirmation of religious truth, and a promise of future reunions with their loved ones. Skeptics saw a deception, an intentional fraud designed to take advantage of terrible grief.

Louis Kaplan writes that, “a contemporary theoretical reading no longer guided by Spiritualist beliefs situates the uncanny spirit photograph as that which enables consumers to forget their losses by restoring the domestic scene, familiarity, and community in the face of the gruesome fact of mortality” always evoked by Mumler’s images.(6) If this is a contemporary reading of the spirit photograph, it leaves something out that would have been apparent to the mourner waiting in Mumler’s parlor. Spirit photographs, at least visually, brought the deceased back to the present and promised a future reunion on the other side of mortality.

Jen Cadwallader suggests that spirit photographs provided some measure of control over grief by redirecting it. They write that “[i]n the spirit photograph, however, the relative positions of mourned and mourner are reversed – as these photographs show, it is now the mourned who watches the mourner. This positioning, this focus on grieving, conveys at a glance… a tribute to one departed, but also… a reflection on the act and value of mourning itself.”(7) When they entered the photographers’ studio, the mourner sought consolation from their dead. When they were able to identify the wispy face of a loved one hovering over them, they got what they came for.

Mrs. Tinkham; William H. Mumler (American, 1832 – 1884); 1862–1875; Albumen silver print; 9.5 × 5.7 cm (3 3/4 × 2 1/4 in.); 84.XD.760.1.7; No Copyright – United States (http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-US/1.0/)

Endnotes:

- This post is focused on the phenomenon of spirit photography. For more on spiritualism in Victorian England, spiritualism and gender politics, and social reform, I would recommend The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England by Alex Owen.

- Quoted from The Strange Case of William Mumler: Spirit Photographer by Louis Kaplan, pg 209.

- “Meet Mr. Mumler, the Man Who ‘Captured’ Lincoln’s Ghost on Camera” by Peter Manseau. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/meet-mr-mumler-man-who-captured-lincolns-ghost-camera-180965090/.

- The Apparitionists: A Tale of Phantoms, Fraud, Photography, and the Man Who Captured Lincoln’s Ghost by Peter Manseau, 41.

- Harper’s Weekly, quoted from Kaplan, 208.

- Kaplan, 223.

- “Spirit Photography: Victorian Culture of Mourning” by Jen Cadwallader, 14.

Further Reading:

- The Apparitionists: A Tale of Phantoms, Fraud, Photography, and the Man Who Captured Lincoln’s Ghost by Peter Manseau

- The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England by Alex Owen

- The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer by Louis Kaplan

- “Meet Mr. Mumler, the Man Who ‘Captured’ Lincoln’s Ghost on Camera” by Peter Manseau https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/meet-mr-mumler-man-who-captured-lincolns-ghost-camera-180965090/

- “When a 19th-Century ‘Spirit Photographer’ Claimed to Capture Ghosts Through His Lens” by Dave Roos

https://www.history.com/news/spirit-photography-civil-war-william-mumler

- “Spiritualist Writing Machines: Telegraphy, Typtology, Typewriting” by Anthony Enns

- “The Dead Still Among Us: Victorian Secular Relics, Hair Jewelry, and Death Culture” by Deborah Lutz

- “Spirit Photography: Victorian Culture of Mourning” by Jen Cadwallader

- Link to Getty Museum’s collection of Mumler Spirit Photogrpahs: http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/search/?view=grid&query=YToxOntzOjU6InF1ZXJ5IjtzOjY6Im11bWxlciI7fQ%3D%3D&options=YToxOntzOjk6ImJlaGF2aW91ciI7czo2OiJ2aXN1YWwiO30%3D