Wide-reaching witch hunts are like fires; they rarely occur spontaneously, are in need of previously established fuel, are started through an initial spark, and are sustained by adding more fuel for it to consume. While these accused witches were hanged or pressed rather than burned, when discussing the Salem witch trials building a fire is an apt metaphor with each stage corresponding to the societal conditions at Salem.

As for kindling, a shifting relationship between Salem’s Town and Village bred resentment and suspicion in the inhabitants of Salem Village and an increase in factionalism between the two areas. As Salem Town grew into a thriving port city the wealth entering Salem was increasingly becoming concentrated in the upper merchant class of Salem Town, with 62% of Salem’s wealth being controlled by the richest 10% of residents. To exacerbate this increasing wealth divide as the seventeenth century progressed, the amount of land owned by an average individual decreased by nearly half, limiting growth of Salem Village’s prosperity.

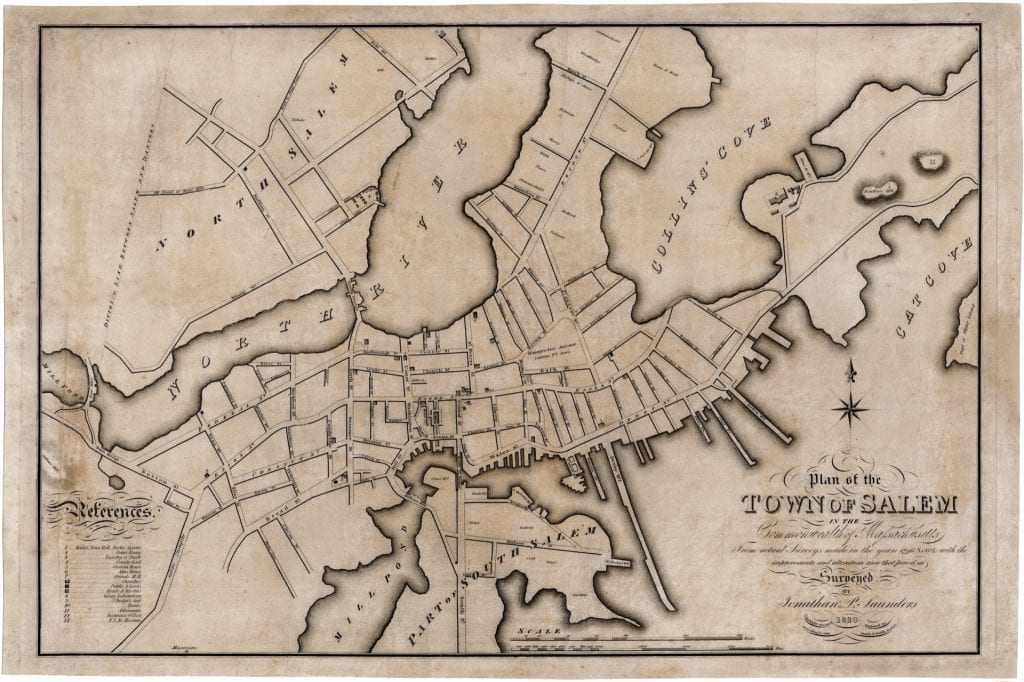

This imbalance also was increasing within representation in Salem’s politics, as in the second half of the seventeenth century merchants outnumbered farmers in elected Town officials by six to one. Thus, the policies that were drafted and enacted tended to favor those of Salem Town than those of Salem Village. For example, the required turns for military watch of the Town were unevenly burdensome on the Village as residents would need to travel several miles to take their watch. In addition, when thirty-one people signed a petition to the General Court asking for relief from these military watches, they also cited that Salem Town was much less vulnerable to attack than the Village, due to the Town’s more compact layout.

Early nineteenth century engraving of Salem Town. Jonathan Saunders, Engraved by Annin & Smith, Plan of the Town of Salem in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

While inconvenience and concern about the future fate of their village plagued the minds of its residents, a powerful Puritan transgression was also at play: selfishness. The pursuit of one’s own interests over those of their congregation was seen as not only a sin against God, but also counterintuitive to community survival. Indeed, the perceived threat posed by these witches were both tangible and physical. Witches’ deeds were said to include the failure of crops and physical harm and those who practiced witchcraft were also said to enter the Devil’s service. Many victims of witch possessions, as pointed out by Carol Karlson, described the process as happening in stages, the first attempting to entice the victim into the devil’s services through material or other desires they might have before torturous possessions began.

Every fire needs a spark and as bitterness between Salem’s factions grew, the tangible harm and spectral evidence needed to begin a witch hunt appeared. In January of 1692, several girls in Salem Village experienced fits, convulsions, and contortions. After being inspected by Reverends Deodat Lawson and John Hale of Beverley, these fits were diagnosed as not being possible through natural means and that bewitchment might be to blame.

Many individuals who were targeted and accused were largely perceived to exhibit values that the Puritans deemed sacrilegious or dangerous to the community. Many characteristics or behaviors could fit the stereotypical depiction of what a witch looked like: women of middling age, abrasive or with a history of bickering, deemed counterproductive to community harmony, and selfishness were all traits associated with witchcraft.

Indeed, evidence against Sarah Good included not only her unwillingness to say that she worshipped God during her trial, but also her history of walking away from disagreements while cursing under her breath. In addition, many others were accused by association with these women, whether by blood, marriage, or close friendship.

Another common type of the accused were those that, while living in Salem Village, had closer ties to Salem Town and its perceived degradation of Puritan values. For example, the owners of two taverns closer to the Town, Bridget Bishop and John Proctor, were both accused of witchcraft, and both were tried, charged and hung for the crime of witchcraft. Not only did their physical proximity to the Town probably factor into accusations, but the fact that their livelihoods were largely drawn from a customer base from the Town would likely raise suspicion.

Another contributor to both the spark and the sustainment of the hunt: the first two alleged victims to show symptoms were the daughter and niece of Samuel Parris, the minister of Salem. As he had held a strong amount of support in the Village, particularly among the less wealthy and less connected to the Town, this may have helped Villagers further associate theTown with degraded values and witchcraft, as he was not nearly as popular with those merchants. The Villagers might have thought the Town considered him, and Village values, as a threat to their profits and individual endeavors.

Reconstructed Salem Village meeting house. Salem Village received the privilege to hire a minister in 1672. Puritan meeting houses served as community centers and well as a place of worship.

Indeed, the victims themselves might have truly believed that this fire could cleanse them. Chadwick Hansen postulates that the first response an individual might have to initial symptoms would have been some fear; but as others, including authority figures, concluded that they had to result from witchcraft, the individual would be more likely to truly think of themselves as bewitched, which would considerably worsen any psychosomatic symptoms. These individuals’ conviction could cause these symptoms to manifest whenever there would be cause to believe that a witch was possessing the individual, such as when the accusers fell into fits while Sarah Good was interrogated during her trial, and likely experiencing anger.

While the hysteria would calm down within the year, like many fires, the result was deadly. Twenty people lost their lives before the denouncement of the trial proceedings. As more accusations and confessions were made and suspicions came to a head the snowball effect of the paranoia would make the path that the events took a deadly one. While it was the last witch hunt in America, it stands as only a single example of paranoia directed towards deviations from an established norm in American history.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England by Carol F. Karlsen

- Witchcraft at Salem by Chadwick Hansen

- “Diabolical Duos: Witch Spouses in Early New England” by Paul B. Moyer

- “The Long and Short of Salem Witchcraft: Chronology and Collective Violence in 1692” by Richard Latner

- Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft by Paul S. Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum