In How We Became Posthuman (1999), N. Katherine Hayles interrogates the shifting representations of the body in societies enmeshed within information networks: “Different technologies of text production suggest different models of signification; changes in signification are linked with shifts in consumption; shifting patterns of consumption initiate new experiences of embodiment; and embodied experience interacts with codes of representation to generate new kinds of textual worlds” (28). The “body-in-flux,” or what Arthur Kroker describes as the notion of “body drift” that Hayles correlates with the dialectic between the pattern and randomness of flows of information renders a dematerialization of representations of both textual and human embodiment. Identifying a shift between signifier and signified, Hayles theorizes the ways in which a “flickering signifier” “brings together language with a psychodynamics based on the symbolic moment when the human confronts the posthuman” (33). Thus, Hayles delineates the ways in which flickering signifiers are “characterized by their tendency toward unexpected metamorphoses, attenuations, and dispersions” that occur within material-informational exchanges (30). Hayles recognizes the ways in which these “flows” or “interchanges” that occur through various types of technology depend on our abilities to understand the shift from “presence/absence” to “pattern/randomness,” not as a way of disregarding the material world, but as a way of understanding shifts of visibility. She argues that “The pattern/randomness dialectic does not erase the material world; information in fact derives its efficacy from the material infrastructures it appears to obscure” (28). Thus, this illusion of erasure should be a subject of inquiry, not a presupposition that inquiry takes for granted.

In her discussion of Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler (1979), Hayles underscores the novel’s metafictive impulse: “The text operates as if it knows it has a physical body and fears that its body is in jeopardy from a host of threats, from defective printing technologies and editors experiencing middle-age brain fade to nefarious political plots. Most of all, perhaps, the text fears losing its body of information” (41). Like Hayles suggests, Calvino’s text reinforces its own version of Jorges Luis Borges’s “Library of Babel,” and Calvino’s development of the interrelationship between reader, writer, and text depicts the dissolution of the modern subject that must constantly be reborn through the reading process.

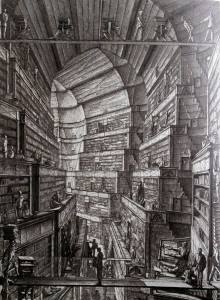

In addition, Calvino juxtaposes the disorder of human relationships with the disorder of his narrative text. However, he recognizes that within this disorder, there can be a recognized order: through the symbol of the labyrinth, Calvino metaphorically gives modern man a way to maneuver through a postindustrial, technological world. He recognizes that the only way for modern man to survive is to move from one labyrinth to the next, the same way that the novel moves from one incipit to the next. According to Calvino’s essay, “La sfida al labirinto” (Challenge to the Labyrinth), he argues, “What literature ought to do is to define a stance for the best way out, even if this way out will entail going from one labyrinth to another. It is the challenge of the labyrinth that we want to save, it is a literature of challenge to the labyrinth that we want to enucleate and distinguish from the literature of surrender to the labyrinth” (qtd. in Weiss 71). Calvino’s labyrinthine incipits are related, yet they evoke difference. This difference, or as Jacques Derrida would say, différance, can also be represented through language. Because deconstruction displaces notions of presence and absence through the randomness and patterns of a network of discourse that is only always a deferral, Calvino’s labyrinth provides no clear beginning and end. His readers are constantly negotiating their roles and the ways in which the text can be interpreted through its empty center. Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler pleasures the reader both inside and outside the text (or so Roland Barthes might say); the text’s labyrinth tropes on the internal and external fluidity of information, creating a fluid methodology of reading.

Like Calvino’s novel, the “pattern/randomness” that dominates the computer interface and seeks to replace the “presence/absence” dualism, however, can prove problematic when thinking about the loss of actual material things (i.e. the environment). If we continue to think about the world through flows of informational patterns and relational ontologies, “a dynamism of randomness,” then we also have to be wary of the frightening disappearance of the material world by man—the epoch that has been termed the Anthropocene—and our roles in that disappearance. I think one way to think about the poststructural/linguistic and ecological/material problems can also connect on a larger scale to the ways in which new materialists articulate concepts of networks of narrative agency. Moreover, Hayles argues that material-informational exchanges depict how “boundaries undergo continuous construction and reconstruction”; therefore, thinking about embodiment within a material world becomes “paralleled and reinforced by a corresponding reinterpretation of the natural world” (3, 11).

Calvino, Italo. If on a winter’s night a traveler. Trans. WIlliam Weaver. New York: Harcourt Brace. Print. 1979.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Visual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1999. Print.

Weiss, Beno. Understanding Italo Calvino. ColumHayles, N. Katherinebia: U of South Carolina P, 1993. Print.

So is it the task of the postmodern (posthuman?) reader to challenge the labyrinth?

How would you rephrase this challenge in terms of the language of decoding that Hayles uses?

Yes, I think so. If, as Hayles asserts, the informational flows that exist between natural language and computer coding create a constant dialectic for the postmodern reader, then the labyrinth becomes something new; thus, code represents an unseen or unconscious language that affects natural language, and too, constantly creates and recreates our relationship to reading. It’s interesting also to think of the labyrinth, I think, in terms of its spatial metaphor here. “Spatial Reading” would then not only include natural language and coded language, but also images. Hmmmm. This blows my mind a little bit! What do you think?

I just rewatched The Matrix Reloaded last night as prep for class discussion, and it’s full of labyrinthian spaces that are altered through codes of access–all the things that Hayles talks about. Minority Report, which Nakamura discusses in part 3, is all about patterns of code taking precedence over presence (that’s pretty much the premise of the whole movie!)

On Windows 10, one of the first things that happens when you set up your interface and access is that they ask you if you want to choose an image to click in place of a passcode. So images become part of that code or a way to talk to that code.

Pretty Great. I need to rewatch The Matrix this weekend…