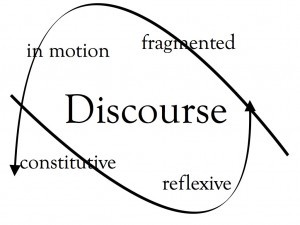

David Eyman begins this chapter by acknowledging that the digitized version of Aristotle’s faithful old rhetorical triangle mirrors a system of interconnectivity rather than a static, threefold framework. He asserts that methods of digital rhetoric must “take into account the complications of the affordances of digital practices, including circulation, interaction, and the engagement of multiple symbol systems within rhetorical objects.”  The relationship among rhetor, audience, digital text or discourse, and contexts reveals a dynamic circulation which can be theorized as an activity. This follows the current trend in circulation studies, which according Laurie Gries is “an interdisciplinary approach to studying discourse in motion” where “…scholars investigate not only how discourse is produced and distributed, but also how once delivered, it circulates, transforms, and affects change through its material encounters” (333).

The relationship among rhetor, audience, digital text or discourse, and contexts reveals a dynamic circulation which can be theorized as an activity. This follows the current trend in circulation studies, which according Laurie Gries is “an interdisciplinary approach to studying discourse in motion” where “…scholars investigate not only how discourse is produced and distributed, but also how once delivered, it circulates, transforms, and affects change through its material encounters” (333).  Although Gries’s concern is methodological — that is, she develops a specific method, called iconographic tracking–-she ultimately argues that rhetoric is “a distributed process whose beginning and end cannot be easily identified. Like a dynamic network of energy, rhetoric materializes, circulates, transforms, and sparks new material consequences, which, in turn, circulate, transform, and stimulate an entirely new divergent set of consequences” (346). Eyman does acknowledge the dynamic flux of discourse digitized; however, he recognizes that traditional rhetorical methods act as a foundational framework within digital contexts: thus, in this chapter, he suggests ways to adapt traditional rhetorical methods into a digital milieu.

Although Gries’s concern is methodological — that is, she develops a specific method, called iconographic tracking–-she ultimately argues that rhetoric is “a distributed process whose beginning and end cannot be easily identified. Like a dynamic network of energy, rhetoric materializes, circulates, transforms, and sparks new material consequences, which, in turn, circulate, transform, and stimulate an entirely new divergent set of consequences” (346). Eyman does acknowledge the dynamic flux of discourse digitized; however, he recognizes that traditional rhetorical methods act as a foundational framework within digital contexts: thus, in this chapter, he suggests ways to adapt traditional rhetorical methods into a digital milieu.

Eyman begins by delineating the differences between the New Critical method of “close reading” with Franco Moretti’s contemporary supposition of “distant reading.” Close reading—methods of analyzing the formal qualities of a text—has traditionally been associated with print text; yet, Eyman claims that it nearly always acts as a fundamental method within digital contexts. As an aside too, digital contexts have expanded our abilities to close-read; check out Amanda Visconti’s dissertation on Ulysses.

However, Eyman also claims that instead of reading the “text-as object” as most New Critics might, reading the formal qualities of a digital text must “include those [qualities] specific to different media.”

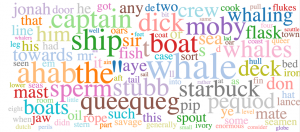

Eyman also describes the inverse of close reading—Franco Moretti’s concept of “distant reading.”Eyman explains that “distant reading takes a long view, examining the text as one among many and considering a much larger corpus whose contexts and relationships give rise to different forms of meaning.” Seeing reading, according to Franco Moretti, as “a condition of knowledge” allows scholars to form a methodology that creates connections between computational analytics and data visualizations.

It also seems that Kurt Vonnegut did, however, have his own view of “distant reading” before Moretti: check it out!

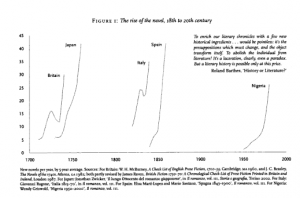

Also, one of Moretti’s visualizations shows the emergence of the market for novels in Britain, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Nigeria between about 1700 and 2000 (see graph). The wild spikes in popularity look like fish hooks, even as each country’s bibliophilia caught on at different times.  So computation plus visualization allow us to get a more complete view of cultural trends than intensive reading of a few works lumped into a canon. Despite criticism of Moretti’s work, author Jonathan Franzen argues that seeing literature as a cultural artifact reveals its agential qualities: “To use new technology to look at literature as a whole, which has never really been done before, rather than focusing on complex and singular works, is a good direction for cultural criticism to move in. Paradoxically, it may even liberate canonical works to be read more in the spirit in which they were written.” I think it’s an interesting conversation also to make us think about the evolution of reading and rhetoric in the digital age: How do we read images? What counts as “text”?

So computation plus visualization allow us to get a more complete view of cultural trends than intensive reading of a few works lumped into a canon. Despite criticism of Moretti’s work, author Jonathan Franzen argues that seeing literature as a cultural artifact reveals its agential qualities: “To use new technology to look at literature as a whole, which has never really been done before, rather than focusing on complex and singular works, is a good direction for cultural criticism to move in. Paradoxically, it may even liberate canonical works to be read more in the spirit in which they were written.” I think it’s an interesting conversation also to make us think about the evolution of reading and rhetoric in the digital age: How do we read images? What counts as “text”?

The evolving field of digital composition engages multiple modes and media; thereby digital composition and rhetorics emerge as collaborative activities that provide broad opportunities for publication and circulation. Eyman recognizes, then, that from professional writing and research, digital rhetoric follows two research traditions: genre studies and usability.

Genre studies privilege “a multilayered approach of both micro- and macro-level interactions,” while usability takes both system and user into account and therefore “provides a methodology for studying both writing practices and writing pedagogies.” By engaging these methods, Eyman contends that theorizing new digital methods will account for modes of professional composition and rhetoric as well as the multimodal, multimedia networks of the digital world. Thus, Eyman notes an increasing amount of research that suggests, obviously, that the very definition of writing and composition have changed in the digital age.

In addition, Eyman suggests that Heidi McKee and Danielle DeVoss’s , Digital Writing Research:Technologies, Methodologies, and Ethical Issues is a prominent collection because it reveals the broadening scope of writing activities, and it also considers a cyborgian and networked view of human communications and also includes theories of triangulation (texts, contexts, and users) and ecological metaphors of digital texts and contexts.

In addition, Eyman suggests that Heidi McKee and Danielle DeVoss’s , Digital Writing Research:Technologies, Methodologies, and Ethical Issues is a prominent collection because it reveals the broadening scope of writing activities, and it also considers a cyborgian and networked view of human communications and also includes theories of triangulation (texts, contexts, and users) and ecological metaphors of digital texts and contexts.

The chapter concludes by explaining a variety of interdisciplinary methods that may be appropriate for assembling digital rhetoric methods. I have listed them below.

1.) C.O.D.E and Network Administration Tools: the study of the networks of digital rhetoric both material and immaterial. C.O.D.E. stands for “Comprehensive Online Document Evaluation,” and unfolds both the geographies and owners of networked systems.

2.) Studying Web Usage via Server Log Analysis: this method analyzes the log files of users; server log analysis reveals quantitative data that shows the change in a site’s traffic data. This shows the relationship between a digital text and its audience.

3.) Social Network Analysis: this is a research approach that focuses on patterns of relationships among people, and it studies relationships in context with other relationships in a network.

4.) Hypertext Network Analysis: HNA is a form of social network analysis that only looks at nodes and ties of digital texts as instantiated in websites and web links. Basically, it analyzes hyperlinks.

5.) Bibliometrics and Cybermetrics: these methods trace the use and value of texts through citation analysis.

6.) Content Analysis: this method is similar to social network analysis, except it focuses on the relationships within an individual text rather than between texts.

7.) Data Visualization: a method used to structure data in ways that visually reveal patterns.

Despite the fact that Eyman is hopeful that many of these methods can be assimilated for digital rhetoric methods, he does cite a few complicating factors. First, he identifies accessibility as an issue: “Accessibility can be impeded by intellectual property gatekeeping (restricted access to networks and texts that circulate in and through those restricted systems, as well as cost-prohibited fees on certain content), but it is also an issue when considering the format of the rhetorical objects themselves.” Second, Eyman also claims that the ephemeral nature of digital texts makes tracking and tracing difficult.

Questions:

1.) How do some of Nakamura’s claims complicate the theorization of digital rhetoric methodologies? What other elements should we consider here?

2.) The lack of traceable exigence within digital rhetoric seems to be a problematic factor. The inability to trace origins fosters a synthesis of roles within immediate rhetorical situations. While classical or modernist views of rhetorical situations rely on the stability of such categories as “rhetor,” “audience,” and “message,” postmodernist and immediate views of rhetorical situations assume these divisions are arbitrary and in constant flux.

How can our methodologies account for this? How does the lack of origin change the ways in which we study rhetoric? Explain.

3.) How might a consideration of these methods help us to do the work of defining Digital Rhetoric as an emerging field?

4.) Eyman’s move towards interdisciplinary methods suggests collaborative, cross-disciplinary research. Yet, how do these methods complicate global versus local forms of knowledge? Can you think of positive and negative consequences of this? How does this affect the field of the humanities in general?

5.) Do you have any specific concerns regarding any of the methods outlined by Eyman?

Works Cited

Gries, Laurie E. “Iconographic Tracking: A Digital Research Method for Visual Rhetoric and Circulation Studies.” Computers and Composition 30.4 (2013): 332–348. ScienceDirect. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Fantastic job on summarizing the highlights of the material and for finding the Kurt Vonnegut video!

Thank you:)

Thanks for the great summary and insights. I think that both close and distant reading of texts has their place in their analysis. This is especially true give the different learning styles of readers. As usual, the true picture of a text’s meaning and message will lie somewhere in between. (P.S. Thanks for sharing that great book on the visuals of distant reading.)

Thanks Phyllis. And thank you for asking a question, too! It helped me out during my discussion!