I think that wikis are an important and fun method to incorporate into the classroom. To start, wikis allow students the flexibility of a cooperative, online learning environment. They also provide students with the opportunity to self-publish, fostering a sense of pride in a finished product that can be viewed online. Thus, wikis allow for the individuality of self-learning in a cooperative environment. In addition, by creating a crowd-sourced model of learning, wikis also create a platform which follows the theory of the Socratic method: students “debate” or “discuss” through both print and visual rhetoric through wikis. Here is a wiki that I like from Skidmore College about Greek Tragedy: http://academics.skidmore.edu/wikis/Greek_Tragedy/index.php/Main_Page

I think that wikis are an important and fun method to incorporate into the classroom. To start, wikis allow students the flexibility of a cooperative, online learning environment. They also provide students with the opportunity to self-publish, fostering a sense of pride in a finished product that can be viewed online. Thus, wikis allow for the individuality of self-learning in a cooperative environment. In addition, by creating a crowd-sourced model of learning, wikis also create a platform which follows the theory of the Socratic method: students “debate” or “discuss” through both print and visual rhetoric through wikis. Here is a wiki that I like from Skidmore College about Greek Tragedy: http://academics.skidmore.edu/wikis/Greek_Tragedy/index.php/Main_Page

According to Kevin Parker and Joseph Chao, wikis also create opportunities which support constructivist learning: “Constructivism is approached from a variety of perspectives in wiki research, including reflective activity and communal or social constructivism” (59). This type of reflective learning allows for the growth of metacognition in important ways, and I also think that it allows learners to become more in-tune in general with their strengths and weaknesses as both learners, and perhaps too, people. There are so many effective uses of wikis, and I think that by incorporating them within the classroom you are not only exposing students to a greater learning experience, but you are also acclimating them to an online environment that they must learn how to traverse in order to be successful in the future.

In addition to wikis, I also think that eportfolios are a useful online tool to utilize within the classroom. I’ve actually seen teachers link individualized eportfolios to a classroom wiki too, which I think is an effective way to display the work of a group of students over a period of time. Again, like wikis, eportfolios help students develop a sense of ownership and pride in their work. In addition, eportfolios enhance procedural learning, helping students understand learning as a process over time. I enjoyed thinking about all of the ways in which eportfolios can be used as cited within the Parkes article.

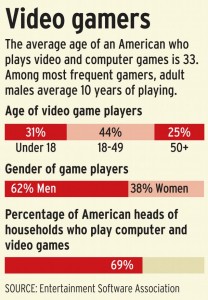

I especially think that allowing students the ability to problem-solve becomes a very important asset of using eportfolios and most types of online methods. The article states, “With increasing opportunities to share and collaborate in class and out, with the use of blogs, the discussion threads, and e-mail communication, students often problem-solve issues and find and share solutions rather than just make a ‘one-stop’ learning goal, such as, ‘What is on the test next week?'”(108). Thus, students become accountable in new and important ways, and they have the agency to think outside of the box in order to find solutions.

The use of online teaching tools such as wikis and eportfolios also suggest the ways in which the classroom is changing in prominent ways. Linked to this discussion, of course, are the changing discourses and methods required in understanding how the Internet and online learning are modifying the ways people think and interact. The BBC episode “The Virtual Revolution” unpacks that very issue: the episode asks, “What are the web’s revolutionary effects on human beings?” The episode investigates whether or not contemporary society, and especially children, are becoming consumed by the Internet. Accordingly, living with “generation web” involves understanding the social interactions that social media cultivates, and in addition, understanding th e feedback loop which requires a constant movement of action and reaction between person and machine. The episode then examines whether or not generation “Homo Interneticus” is indeed drowning in a sea of information, or perhaps growing from the associative linking that is crucial to Internet interactions.

e feedback loop which requires a constant movement of action and reaction between person and machine. The episode then examines whether or not generation “Homo Interneticus” is indeed drowning in a sea of information, or perhaps growing from the associative linking that is crucial to Internet interactions.

Understanding both the benefits and weaknesses of “hyperlinked” associative learning becomes a crucial part of this discussion: does associative linking keep our brain “jumping” in productive ways? The web’s associative platform allows students to interact and work together in new ways, creating a global learning environment; thus what emerges is the notion of a global brain. In all, “The Virtual Revolution” highlights the importance of studying the impact of the Internet on current and future society. It highlights how the Internet holds a mirror up to human nature, allowing us to reflect upon the good and the bad. Furthermore, studying the Internet and its impact also allows us to perceive how the newest generation is indeed evolving. Thus, the episode’s resounding message asks whether the Internet will change human nature for the better. I am hopeful that it will.

![[ File # csp9576691, License # 2840127 ] Licensed through http://www.canstockphoto.com in accordance with the End User License Agreement (http://www.canstockphoto.com/legal.php) (c) Can Stock Photo Inc. / olechowski](https://you.stonybrook.edu/digitizerhetoric/files/2016/03/problem-solving-28yi50g-300x300.jpg)