“We are as free as birds. Only the birds aren’t free. We are as committed as birds and identically.” —John Cage

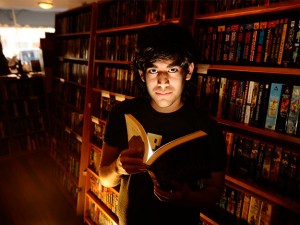

Thinking about the heartbreaking story of Aaron Swartz this week calls to mind the John Cage quotation mentioned above. Aaron’s activism and groundbreaking work in media and technology which results in his tragic fall highlights the corruption that governmental controls have on access to education and information. Aaron’s story is one that stresses how different types of crimes can be conflated in unjust ways; or, how society restricts civil liberties.

In addition, the mourning of Aaron’s life also brought to mind John Durham Peters’s recent book, The Marvelous Clouds: Towards a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Part of the argument in Peters’s book brings to light the ways in which media has become part of an infrastructure that not only discloses information and messages, but also reflects the ways in which existence and expression merge. Peters argues how media embodies Donna Haraway’s concept of naturecultures (one word): thus, communication becomes a disclosure of being, and Peters investigates how this reconstructs the ways we think about the intertwining of nature and culture (and other binaries that follow suit). Thus, for Peters, media crafts existence, reinforcing a movement from the figure to the ground.

I thought about Aaron’s life in conjunction with this book because of the ways in which his existence became so strongly documented by his online presence and by his information activism. Like Peters, it seems that for Aaron, media held ecological, existential, and ethical imports. Moreover, the “marvelous clouds” that represent the ethereal conditions of Peters’s notions about media, also represent Aaron’s lasting legacy as “the internet’s own boy.”

strongly documented by his online presence and by his information activism. Like Peters, it seems that for Aaron, media held ecological, existential, and ethical imports. Moreover, the “marvelous clouds” that represent the ethereal conditions of Peters’s notions about media, also represent Aaron’s lasting legacy as “the internet’s own boy.”

Certa inly, Aaron’s story can be used as an example when discussing some of Lawrence Lessig’s claims in Remix: most notably how notions about copyright must be redefined in our current age for younger generations: “In a world in which technology begs all of us to create and spread creative work differently from how it was created and spread before, what kind of moral platform will sustain our kids, when their ordinary behavior is deemed criminal?” (xviii). Lessig calls for a remapping and remixing of our “cultures of creativity” in order to take into account what creativity and autonomy mean in our technological moment and the future (18).

inly, Aaron’s story can be used as an example when discussing some of Lawrence Lessig’s claims in Remix: most notably how notions about copyright must be redefined in our current age for younger generations: “In a world in which technology begs all of us to create and spread creative work differently from how it was created and spread before, what kind of moral platform will sustain our kids, when their ordinary behavior is deemed criminal?” (xviii). Lessig calls for a remapping and remixing of our “cultures of creativity” in order to take into account what creativity and autonomy mean in our technological moment and the future (18).

Throughout the text, Lessig’s movement among market economies, changing technologies, and cultures past and present develops an extraordinary lineage of the transitory faces of culture. In addition, I think his position on the current hybrid nature of creativity, and the “remixing” of art forms through technology shifts our current ideas about what it means to be in what has otherwise been called a culture of consumption, or “copying.” Furthermore, thinking about remix as a collage or montage of creativity also suggests a primacy of meaning leveraged by the motivation to synthesize and build something new (76). To consider art and culture this way fosters a way of thinking about individual expression within a community of ideas. I think this book is great.