In Herman Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street (1853), Melville constantly manipulates the reader’s expectations. A self-reflexive commentary on the life and death of reading, Bartleby’s letter-reading and life-writing (or not-writing, because, after all, Bartleby “prefers not to”) critiques our understanding of reading and a nature of “work.” We find ourselves today refiguring our work and practice in the digital age. As teachers and scholars, it becomes important to situate reading and learning by teaching texts anew: we need to move ourselves away from Melville’s dead-letter office, and rather, posit learning within moving texts and contexts that define modern life.

Douglas Eyman covers a range of methodological and pedagogical forms for digital rhetorics in the final section of his text. His concerns regarding the engagement of multiple platforms and methods emphasize not only an expanse of differentiation techniques, but also reaffirm his assertion that the multimodal and individualized perspectives of digital rhetorics must be accounted for within teaching practice. The digital rhetoric courses that Eyman describes in order to give a range of views highlight the principles and practices of instructors who focus on both theory and production. Of the three courses depicted, I like Eyman’s own course the best; with a focus on production, Eyman’s method immerses students into the actual theoretical and experiential space of inquiry. Thereby, students become acclimated through constructive educational practice. By experiencing the multiple perspectives of digital rhetorics, students have the ability to uncover theoretical and practical facets of their own production and practice within the expanding field of digital rhetorics.

Eyman also cites Jim Zappen’s article “Towards a Digital Rhetoric” in order to highlight the ways in which Zappen’s focus coincides with his own; Eyman delineates Zappen’s main aims: “refiguring rhetorical traditions for digital texts, defining characteristics of new media, developing digital identities, and forming online communities.” By focusing on the categories of work within digital rhetoric discourse, Zappen also depicts the field of digital rhetoric production, practice, and theory as a method of inquiry. I think this is also an effective way to think about digital practice and discourse because of its variable nature. The digital world provides a valuable infrastructure to so many parts of our lives, and understanding the infrastructures of discourse and rhetoric relies on online communities of learners who understand and engage the mercurial nature of those infrastructures. Plus, this type of engagement also calls for a continued inquiry into the affordances of new media texts.

In addition, Eyman’s philosophies also stress the mobility of the learner by grounding method within interactivity which he renders through the work of several scholars. Aside from focusing on student interactivity, the final sections of Eyman’s text focus on a variety of remix projects along with works that underscore creative appropriation and editing. He reinforces the creative works of scholars and students who are engaged in rescripting and refiguring texts and media into new forms. The multimodal content of the projects are pretty impressive. After reading this text in its entirety, I think that Eyman effectively demonstrates the ways in which classical and contemporary rhetorical aims come into play when thinking about constructing theories and methods for digital rhetorics. I also like the ways in which this website by Claire Lauer of Arizona State University deals with understanding and defining digital rhetorics through a rose metaphor attributed to Juliet’s famous “What’s in a name?” soliloquy in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet: http://kairos. technorhetoric.net/17.1/inventio/lauer/index.html

technorhetoric.net/17.1/inventio/lauer/index.html

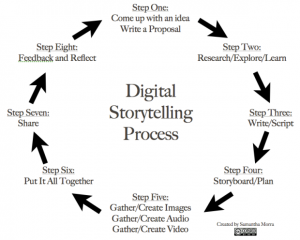

The emphasis in this week’s class on digital storytelling, also, I think brings to light Eyman’s aims of remixing new and old. Digital storytelling seems to be an important area to situate teaching practice because it reinforces digital literacy, multimodal forms, and a visual/textual forum that promotes creativity. Also, it can be used within a variety of classes for a variety of reasons.

Also, as a teacher, I think that the procedural  phases of learning that are associated with such a project are beneficial. Students have the opportunity to reflect upon their own creative process while revising as they go. This most mirrors a real-life work space where people are able to reassess and reconsider their own weaknesses.

phases of learning that are associated with such a project are beneficial. Students have the opportunity to reflect upon their own creative process while revising as they go. This most mirrors a real-life work space where people are able to reassess and reconsider their own weaknesses.

Finally, this blog by Scott Garbacz offers some great teaching ideas about how to man “the digital divide” in the classroom: http://bloggingpedagogy.dwrl.utexas.edu/content/canvas-tutorial-or-how-not-enforce-digital-divide