This summer, I’ve begun drafting the first two chapters of my dissertation (which, in fact, are the last two chapters of my dissertation, as my advisors suggested that I begin with whatever I’m most interested in). While thinking about how to approach these first chapters, I’ve decided to employ some of the past exercises that I’ve required of my own writing students. I’ve heard a number of accounts from more senior academics who state that they do complete their own assignments to ensure their efficacy and usefulness.

This summer, I’ve begun drafting the first two chapters of my dissertation (which, in fact, are the last two chapters of my dissertation, as my advisors suggested that I begin with whatever I’m most interested in). While thinking about how to approach these first chapters, I’ve decided to employ some of the past exercises that I’ve required of my own writing students. I’ve heard a number of accounts from more senior academics who state that they do complete their own assignments to ensure their efficacy and usefulness.

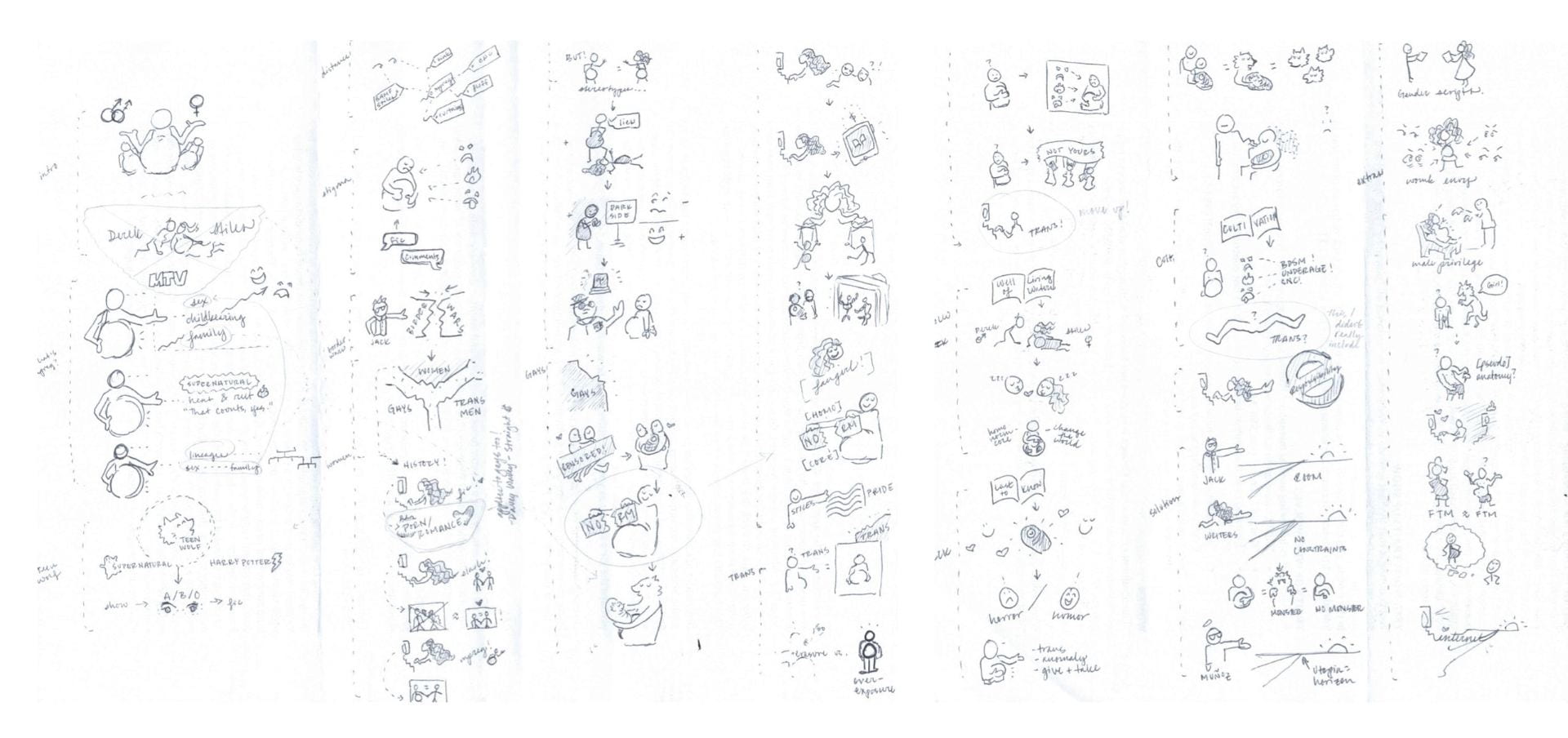

Accordingly, after drafting out my chapter (“Shitty First Drafts“-style) on fan fiction, the mpreg trope and the border wars that emerge through it, I decided to illustrate the organization I’d created as a means to think through how I actually wanted to structure this chapter.

This comes from an exercise that I first learned from Professor Patricia Dunn at Stony Brook in her “Teaching English Literature” course in the Fall of 2017. The steps are fairly straightforward. After providing paper and colored pencils, you ask students to map out their essay in a visual way. If someone asked you how your essay was organized, how would you respond? Illustrate this. After an allotted time (five minutes or more), challenge students to think of an alternative way to organize their papers. Now being able to see your essay mapped out in front of you, how might you organize it in a different way? I’ve noticed that students rarely want to share these drawings with the entire class, so I often have them think, pair, share as a way to discuss their experiences and findings at a low-stakes level.

I’ve led this exercise for students in both literature and writing courses, and it’s fairly straight forward. It also provides useful benefits, with students often surprised by what they discover they can see in their organization (or lack thereof). This adheres to Lynda Barry’s work on writing, thinking and drawing, through which she ultimately points out that drawing makes our brains work differently; we think differently when we’re drawing.

As I finished my first draft of “Pregnant Teen Wolf,” I decided that I, too, would also map it out in a visual manner. While the papers my students map out are generally shorter (3-5 pages), the draft of my chapter was over 30 pages long. As a result, my illustrations (usually about one drawing per paragraph) were a bit more extensive than what I would expect from the in-class exercise. I ended up taking several hours to work through my whole essay. My illustrations are below.

At the end, I not only found instances where I wanted to move certain sections; I also found that I had a much better grasp regarding the entire contents of my work. Being able to see all that my chapter contained at a glance, I have a better understanding of the larger trajectory as well as the individual threads that make up the “larger picture.”

A side note: of course, my illustrations make more sense to me than they would to someone else. Nevertheless, it’s rewarding to see something physical that you’ve produced through the labors of your academic work.

Leave a Reply