Semester by the Sea

As part of the coursework for their classes, students create blog entries about their experiences. Read about their adventures below!

MAR 355 – Coastal Cultural Experience; Witches

Witches Around the World

|

| Nigerian witch doctors dressed in clothing and carrying amulets designed to combat Lassa Hemorrhagic Fever |

Native American Witchcraft

|

| Portrayal of a Navajo skin-walker dressed in the skin of a coyote or bear. These witches were seen as dangerous, hence the spear in hand. |

|

| A fox witch, or kitsune-mochi, scaring a prince. Fox witches were seen as tricksters, sometimes playful and sometimes more nefarious! |

Photo credits:

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/witch-hunting-and-women-art-renaissance

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witch_doctor#/media/File:Lassa_witch_doctors.jpg

https://rivercityghosts.com/the-terror-of-the-skinwalker-the-native-american-boogeyman/

It is the unfortunate truth that women tended to be the main target of the witch trials that took place throughout Europe and the American colonies in the 17th century. The main cause of this idea was information based on the Malleus Maleficarum, a book written for the public to aid the witch hunt. This book dubbed women to have “familiarity with the devils,” and that they were the gateway to the devil himself. In the Chritian community, it was widely believed that women were less than men due to Eve being birthed from one of Adam’s ribs. Women were also not trusted much, since a woman (Eve, again) was the one who caused all of humanity to be chased away from Eden.

While today when we think of a witch, we often think of an old green hag riding a broomstick at night, it was not until later that witches were linked to brooms. The original connection between the two is thought to have become common by the idea that female witches would put a broomstick in their place when leaving bed at night so their husbands would not notice their absence.

The Malleus Maleficarum: All You Need to Know About Witches

Now a reasonable question might be to ask, what inside this book makes it so popular? Well, the answer might shock you. As stated in the work, witches were said to kill babies and have sex with demons. Not only that, but they had a tendency to steal men’s penises. This was a witch’s way of taking away a man’s power. Some telltale signs that a witch is living amongst you, according to the work, is that a witch would have a “witch’s mark” aka a birthmark. It was said that if you prick this mark with a pin and the person doesn’t react, they’re a witch! Another useful tidbit was that witches cannot cry. So if you suspect someone is a witch, maybe ask them to cut you some onions. If their eyes stay cold and dry, they should be burned at the stake!

The Witchcraft of Easthampton

A few decades before the infamous events in Salem there were actually witch trials that happened even earlier in the town of Easthampton. In this town in 1658, a young girl named Elizabeth Gardiner got ill all of a sudden after recently giving birth. While people were treating her she all of a sudden said “A witch! A witch! Now you are come to torture me because I spoke two or three words against you!” And she said this because she saw a black figure standing at one foot of her bed while Goody Garlick, who was one of the people helping her, was standing on the other foot of her bed. Shortly after this Elizabeth’s father Lion Gardiner, who was the town’s most prominent person, was summoned and Elizabeth told him what she saw.

Unfortunately only a day later Elizabeth died, however, her actions would have a big impact on the forthcoming events of this town. And after Elizabeth’s death, many people started to accuse Goody Garlick of mischievous things such as blaming her for the death of livestock, sending out familiars to do her bidding and there was even an accusation where people said that she killed a baby just by holding it. So after all of these accusations and after Easthampton magistrates collected every testimony they went to a court in Connecticut. Once this happened a trial ensued where the court eventually came to a decision and declared Goody Garlick not guilty because there was not enough sufficient evidence to prove that she was a witch. After this decision, Goody Garlick returned to her normal life however with all the accusations though most of the townspeople still didn’t treat her very well.

Easthampton

by Nicholas Ring

The Wicked Witch of the West is a classic design that has lasted throughout the ages. But how original was this design? To answer this question we look back to the late 1400s to see where this design originated from, the Malleus Maleficarum.

The same monster that formerly hunted people’s nightmares and caused the direct or indirect deaths of over half a million people, is now a classic costume for people to wear for halloween. How did this happen? I think the answer lies with L. Frank Baum’s, The Wizard of Oz. First written in 1900, followed by a now classic movie adaptation in 1939, it depicted the Wicked Witch of the West as an old, sour, uggly, conniving, pilot of a broom stick. All of those ideas have their sources in Pope Innocent VII book the Malleus Maleficarum.

|

| This is the original cover of the Wizard of Oz from 1900. |

Malleus Maleficarum, or The Hammer of Witches, was written by two Germanic monks, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, the Hammer of Witches was written in 1486 as an end-all be-all book of how to identify, capture, and kill a witch. According to the Malleus Maleficarum witches dealt with demons, and used them to spy on everyone in order to see when they were weak. A black cat was one demon they used to do this. After patrolling the streets they would return to the witch and and succle on a Mole, Wart, or any other deformation and transform the knowledge that way. They would also meet past midnight and work in their secret covans. In order to hide their disappearance from their husbands they would replace themselves with brooms. Not that they weren’t also claimed to fly on broomsticks. Witches were also infamous for putting curses on their victims to either create more witches, many of these spells requiring eye contact. One of the best ways to find a witch is with water, as water is pure enough to repel a witch, meaning they will float. This book along with its shortened successor, Demonology, was used to identify and prosecute witches throughout the 15th to the 18th century. Its use was so widespread that it held the record for being the second most printed books throughout that time. The novel is not used to identify witches any more, however the Malleus Maleficarum still influences our view of witches to this day.

|

| The Malleus Maleficarum original cover from 1486 |

The Wicked Witch of the West is heavily influenced by the Malleus Maleficarum. Flying on a broomstick is a clear reference to the legends of witches flying on broomsticks. The wart found on the witch’s chin is also a reference to warts being an identifying mark of a witch. Her green color may seem like a creative choice by the author; it would seem that she turned green from a magic tonic fed to her mother while she was pregnant with the soon to be witch. This could be influenced by midwives’ history of accusations. While she has no black cats, an army of flying monkeys that go out and search for Dorothy are an adequate demonic replacement. The Wicked Witch of the West often uses spells to subdue or attempt to delay Dorothy. She does not need eye contact, she uses a crystal ball to see Dorothy to cast her spells while she can’t see Dorothy directly. The Wicked Witch of the West’s death was caused by water. While water was never used to directly kill a witch, it does portray the pure nature of water. These features might not have been taken directly from the Malleus Maleficarum, but display the cultural influence that witches held. Thanks to works like The Wizard of Oz, witches have become something harmless enough to let your children dress up as for halloween.

Torture of Those Accused of Witchcraft

Trial by Water was one that didn’t require any devices. Women accused of witchcraft would be tied up and tossed into some body of running water, which was supposed to represent purity. If the women floated, they were considered guilty of being a witch. If they sank, they were innocent. The idea was that a woman that was a witch would have severed their ties to Christianity, and floating would be symbolic of being rejected by the purity of the running water. It was an outlawed practice due to the dangers the innocent faced, yet it was still carried out during these witch hunts.

It’s shocking to say that these aren’t even the worst of it all, but the ones more relevant to punishment of those accused of witchcraft. These were used not only used to get a confession, but to also force someone to name others as suspects. Surviving any of these would likely end with being burned alive, which was symbolic in that it representing the erasure of the individual’s existence both physically and spiritually.

MAR 355 – Mystic Seaport; Oct 22, 2021

In touring Mystic Seaport Museum, one becomes immersed in New England’s world of whaling in the 19th century. Whaling played a critical role in the development of New England as whale oil was their greatest export; it brought economic prosperity and shaped New England societies. Whale oil was a highly sought-after commodity as it was used to fuel lamps, provide lubrication, and make candles and soap. Whaling was one of the largest and most profitable businesses of its time, but it contained great risks and hardships for those involved.

The use of whale oil eventually began to decline in the late 19th century due to the introduction of petroleum, causing the whaling industry to die down. The United States officially banned whaling in 1971. Today, we understand that it is wrong to overhunt and exploit these animals. During the 19th century however, New Englanders only saw this animal as a commodity. Although it is devastating to imagine all the animals that died due to these activities, it is important to remember that the whaling industry helped to establish the economic and social foundation for New England to grow and become what it is today.

by Molly Showers

by Jake Guyer

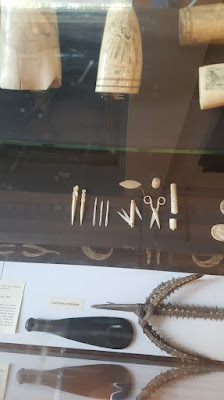

Scrimshaw is the act of taking the byproduct from any marine animal and either carving or engraving some type of image or art onto it. Scrimshaw was extremely common for sailors back in the day especially those who were on whaling vessels. Due to whaling trips being on average about 3-5 years eventually, the sailors on board would read all of the books that were on board thus in order to pass the time they would make scrimshaw. For whalers, the most common form of scrimshaw was of a sperm whale tooth since it was the only whale that they hunted that had teeth. Other forms of scrimshaw also include narwhal tusks as well as hippopotamus tusks.

|

| This image shows the scrimshaw of many sperm whale teeth and as you can see there are many different engravings on them. The engravings vary from women and ships to even whales as well. |

How Song Transformed the Sailing Life

Sea shanties have been a part of our life for as long as we can remember. We all, in one way or another, know some part of a sea shanty. We tend to think of these songs as a way for sailors to pass the time out at sea, in between their shifts or when on whaling vessels, maybe sung through the boredom when there were no whales to speak of. While that could be a part of the reason these songs are so well ingrained into our minds even today, sailors used these songs as a form of rhythm while they worked on the vessel. Working with heavy equipment and rigging held by ropes meant that a lot of men needed to work together to move the equipment, and they had to work in sync in order to work efficiently.

The oldest shanty that we know of is a poem called “The Complaynt of Scotland”, printed in 1549. Between then and up to the 18th century, there is not much about shanties that we are aware of. The 18th century was around the time where traveling the Atlantic was much more commonplace, as trade routes to different continents opened up.

There were a few shanties that we heard at Mystic Seaport of the many songs that exist today. A lot were used for rhythm, such as “Storm Along John”, which was used to keep the rhythm when raising the anchor, and “Haul Away Joe” was used to raise sails. Though there were songs that went further than that, a song about whaling specifically, to keep the crew focused on their mission. Another song, which was not a sea shanty, but was sung by the wives of sailors and whalers, and became the stepping stones for the modern feminist movement, as well as the abolitionist movement.

Shanties are not just the songs we think of as drinking songs, but they actually had a much greater purpose in the maritime world, and eventually, the world beyond. They were, and still are, a great part of culture today, even when we don’t often think about it.

The Best of Both Whaling Worlds

by Abighail McKinney

This week we visited Mystic Seaport in Connecticut. There was a portion of the trip where we learned of the history of whaling and the political relationships formed with different ethnic groups such as the Aivilk Inuits. This group of people lived in the western region of the Hudson Bay and had personal relations with some of the whalers who were heavily involved in trade.

As we know, in the 19th century the demand for whaling oil increased tremendously. Whale oil was the driving force for the industry, it was the preferred type of oil used in the daily lives of New Englanders during this time period. This type of oil was essential to the maintenance of lighthouses, it sustained the fishing/whaling industry and was used practically everywhere!

Sailors were usually at sea from somewhere to 3-5 years depending on their objective, the longest recorded voyage lasted 11 years on the ship Nile in 1858. As you can imagine, whalers at sea commonly missed their wives and children. As well as all the simple things of the land. As a way to remember this, they made art on the ivory made of various mammals/marine animals. This was a method of using many parts of the whale despite its main purpose being oil wax and other valuable commodities. It was also simply a way to pass the time.

Here is an example of the beautiful scrimshaw art created by sailors. Usually scrimshaw’s value wasn’t worth much but we see an increase in later years due to luxury and demand.

As stated above here is a photo of the whale-gut parka that was commonly utilized among the indigenous Inuit people. This is a display of how sustainable they were with their catches, and how important it is to make use of every part of the animal.

I personally think it’s interesting how an entire art form is derived by the simple relationship between two different groups of people. Such talent emerging from a common interest is truly a beautiful thing!

Here is a photo of other types of scrimshaw, we can assume these were tusks of walruses or other animals in the local area and were traded amongst different groups.

MAR 355 – Montauk Lighthouse & Walking Dunes; Oct 15, 2021

Montauk Point, Fishing Capital of the World

by Sasha Josinsky

When I saw that we had a trip to Montauk Lighthouse planned for October 15th on the syllabus for MAR 355, I was overcome by feelings of excitement and anticipation. These feelings came from my passion for fishing and previous experiences around Montauk. When I first visited the point with my family, we happened to visit on an overcast day during the fall around ten or so years ago. I remember witnessing fishermen wearing waders and wetsuits wielding long ten and eleven foot rods casting bucktails and all sorts of lures into a flurry of birds, landing some impressive sized striped bass. At the time I was still a novice in fishing, and the seven foot rod and Gulp! Shrimp we had on hand were terribly ineffective at catching anything, even though we could see the fish right in front of us. I was debating asking my professors if I could bring a fishing rod, as we would be visiting the Fishing Capital of the World during the height of the fall run.

While at the Point we visited the museum, which was filled with lots of information about the many facets of the history of Montauk Point. I was eager to see the exhibit focused on fishing. Images one, two, and three showcase notable catches in Montauk, placed in their respective places over a timeline of more general American history. Montauk was always known as a destination with awesome fishing, and although the fishing has generally declined, it can still be considered as one of the best destinations in the world during the summer and fall months. Of notable mention is the picture of the Blue Whale in Image one and the picture of Frank Mundus, the inspiration behind the character Quint in Jaws, holding the jaws of a White shark in Image three. There is also a mount of a 63lb Striped Bass, one of the most sought-after species of fish in the Northeast, at the top of Image two.

Images four and five showcase some of the gear used by fishermen in the early 20th century around Montauk Point. It’s interesting to note that while some parts like the rods and reels have greatly advanced since that time, other gear like the lures in Image four and the waders in Image five haven’t changed all that much and have remained essentially the same.

|

| Image 2 |

|

| Image 3 |

|

| Image 4 |

|

| Image 5 |

Montauk Lighthouse

by Kay Berenter

There’s something so unusual about lighthouses and the idea that they seem to always house a spirit. The Montauk lighthouse is no different in that regard. This spirit, named Abigail, was said to have been in a wreck just off the coast by the lighthouse. The legend claims that while she was able to make it to shore, she got no further past the lighthouse when she passed. From what I was able to find, Abigail does not seem to be malicious, but a very classic case of furniture moving on its own, unexplained noises being heard, and visitors claiming they feel someone tugging on their clothes.

I’m not one to necessarily believe in the supernatural, though ghost stories have always been fascinating to me. What is the draw towards these stories of death? Why do we tend to bask in the macabre? Perhaps it’s our interest in the unknown afterwards, or the desperation to cling onto the idea of life after death. Or, perhaps, we just like to tell stories in order to keep our eyes open in the dark. Whatever the pull is to ghost stories, I have a feeling we, believer or not, will almost always listen to them.

Happy Halloween!

|

| “The Ghost in the Lighthouse” Terry Flanagan This painting portrays Abigail in the Montauk lighthouse, looking out the window at the wreckage of the ship she was on. |

Model Boats!

|

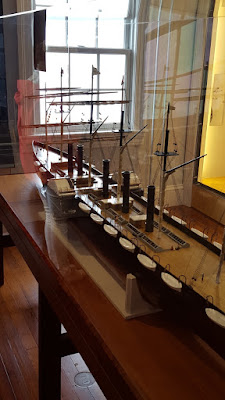

| Image 1: One of the boats on display. Model boats served as blueprints to plan out the construction logistics and physics behind a boat that was to be built. |

This past week our class went to visit the Montauk Lighthouse. Visiting the lighthouse made me think about why do we visit the lighthouse? And why is the lighthouse a tourist destination? The Montauk Lighthouse was commissioned in 1796 to help sailors navigate around Long Island. With time the Montauk Lighthouse evolved to be a symbol for Long Island. The lighthouse became a place of cultural and historical importance for the Long Island community, especially here on the east end, and a part of the local identity. Upon the lighthouses creation it was not built to still stand today because the land that it was built on was supposed to erode away by now. Montauk Lighthouse sits right at the end of Long Island and faces the full force of the Atlantic Ocean’s waves and winds that slowly chip away at the land there.

The Indigenous People of Montauk

I was surprised when Dr. Bretsch and Dr. Rider told us that for our last stop in Montauk, we would be stopping at the walking dunes. These dunes (Pic #1) are formed from predominant northwest winds that have pushed sand for over a hundred years towards inland. They are called the walking dunes not only because people can walk on them, but also because over time they appear to be “walking” through the forest. The sand dunes move roughly 3.5 inches a year, move directly through the land regardless of what is in the path, and they can get up to heights of approximately 80 feet.

|

| Pic 1 |

|

| Pic 2 |

|

| Pic 3 |

MAR 355 – Fire Island Lighthouse; Oct 1, 2021

The Old, the New and the View: the lighthouses of Fire island

by Jonah Tom-Wong

Monarch Butterfly Migration

I have always had a special connection with butterflies. Perhaps it could be from running around in my backyard catching them in my net when I was little, or that I now view them as signs from people who are no longer with me. Regardless I view butterflies as beautifully unique, so when Dr. Bretsch said we were going to Fire Island to see the Monarch butterflies migrate south for the winter, I was excited. He discussed how in previous years there were so many butterflies that they would land on students, however, we went a couple of weeks early, so there were not as many butterflies. As we walked towards the lighthouse on the boardwalk, a few flew past me, but I was not quick enough to get a picture. When we finally arrived at the beach, Dr. Bretsch told us all about the Monarch butterfly.

Robert Moses, Fire Island

by Amanda Tepper

This past week my class and I took a trip to Robert Moses State Park, which is a part of Fire Island. Robert Moses State Park is a beautiful place to visit and to walk around, with trails that can lead you to the lighthouse or the sandy beach. It was designed as a place for New Yorkers to escape to and enjoy the fresh air and nature. The Park is a great place to explore, to take in the sights of the plant life that flourishes on either side of the path, enjoy the crashing waves on the shoreline or even bird watch if you are so inclined. Just be careful to avoid the poison ivy! There is much to see even if you do not manage to make it up the lighthouse (though I do recommend doing so since the sight from up top is breathtaking).

The Internal Mechanics of a Lighthouse

This week, we went out to Fire Island and visited the Fire Island Lighthouse. One thing we learned about was the mechanics inside of the lighthouse and its moving parts. We were shown the lamps of the lighthouse, beginning with the single circular wick Argand lamp which then developed into the multi-wick lamp. These multi-wick lenses were used in the Fresnel lenses of the lighthouse. In 1881, a four-wick lamp was used and had the brightness of about 400 candles. The Fresnel lens then turned that light into eight beams, each of the brightness of 65,000 candles.

Another mechanism we looked at was the clockwork, which controls the rotating lens to produce a periodic flash of light. Each lighthouse has a unique flash that helps to differentiate it from other lighthouses, something that was critical to sailors at night to determine which area of land they were near. The Fire Island Lighthouse clock rotates the lens every eight minutes to produce a 5 second flash every 55 seconds.

Image 2: This is the original clockwork, which was based off the standard pendulum clock that was then further modified for rotating Fresnel lenses.

Fresnel Lenses: The Invention that Saved a Million Ships

by Aaron Ohm

The Fresnel lens was invented by the French physicist, Augustin-Jean Fresnel in 1821 for use in lighthouses. It was based on the theory that light has the properties of a wave. Since its first usage in 1823, this invention quickly spread across the globe. Though it only arrived in the US in 1852, 500 new lighthouses were built within the next 10 years to support the more powerful lenses.

Image 1 is a picture taken at the top of the Fire Island lighthouse looking towards the southeast. In the center of the image towards the bottom you will notice a small triangular freshwater lake. Fire Island is large enough to have its own fresh water aquifer. Local wildlife including deer and fox drink here.

Image 2 is a picture taken at the top looking towards the northwest. We were very fortunate to have spectacular weather during this trip and the New York skyline can be seen in the distance. Uptown is towards the right and downtown towards the left.

Image 3 is an awesome photo taken by Stephen Mastrorocco with perfect timing. He was able to photograph a bolt of lightning next to the lighthouse right when the light was facing his direction.

Fire Island was also a hub for Rum Runners during Prohibition. There is a funny local story about a captain of a fishing boat out of Babylon village dock. During the day he took out fishermen. At night he ran his boat to the Coast Guard territory line to a large ship just outside the coast (3 miles) to buy liquor and haul it back to Babylon to sell. One night, he was about to be boarded by the Coast Guard and he had the money to buy the liquor. When he saw them coming, he put the money in the toilet. They did not find it. In the Fire Island town of Lonelyville, there is an abandoned track that was used to haul booze from the ocean side to the bay side for shipping to the mainland.

MAR 355 – Riverhead; Fish Ladders & New York Marine Rescue Center, Sept 24, 2021

Fish Ladders

What are fish ladders? In a way its fairly self-explanatory, fish ladders are a way for fish to get from one elevation to another. Granted, they don’t have rungs or generally look like human ladders, but the concept is the same.

The first fish ladder was built in the 1830s by an engineer in Scotland named James Smith. Smith created this with the same intention that we have today: Smith noticed that due to a dam being constructed for a mill, the salmon were unable to get upstream. He devised a series of pools at incremental heights so that the fish could jump over multiple smaller obstacles instead of a single large one. This technique is known as a pool-and-weir fish ladder and is still one of the most common types of fish ladders today.

|

| Photo 1 |

Fish and Rescue

The Limits of Rehabilitation with Funding

by Clare Dana

This Friday we toured the New York Marine Rescue center in Riverhead, New York. We got a chance to tour their facilities, meet some of their current rehab residents, and learn about the ins and outs of the process and what it takes to run this rehabilitation center. The center currently has the ability to rehabilitate turtles, seals, and small cetaceans. Being the only affiliated Marine Rehabilitation Center in New York, they respond to all strandings and reports of injured marine animals in the area. Our guide, and the director of the center, mentioned that the center used to respond to large cetaceans but have stepped back from that because of resources. On top of that, they also had to step back from housing small cetaceans in their facilities for the same reason. This struck me and made me realize the limitations that arise due to funding in the marine conservation field. Seeing that the only center for rehabilitation in New York is limited to specific species because resources cannot be supported is quite saddening.

The director told us how up to 2017 the center would respond to whale strandings (which usually resulted in euthinasia) and could support small cetacean rehabilitation at the center. She also pointed out the tanks that used to be used for the small cetaceans, one of which is now being used for loggerhead being rehabilitated. We must recognize just how expensive this process is between uptake and maintenance of the facility, medications, and food all being provided by a not-for-profit organization. Even beyond the rehabilitation stage when animals are released, the tags used to track them can each cost somewhere between $5,000 and $15,000 so the center must choose what animals will receive these.

Image1: This is Chestnut, a forever resident at the rescue center. Chestnut was struck by a boat causing an imbalance of buoyancy in her shell so she cannot be released. The rescue center has created a contraption to help Chestnut to stay balanced. Chestnut’s little body band is just one example of what the rescue center needs proper funding for to ensure a comfortable life for the injured animals.

Image2: This is Queen. She is the loggerhead turtle that is currently residing in the tank that used to be used for the small cetaceans the rescue center used to house and rehabilitate.

by Abighail McKinney

This week’s class took a visit to the NY Marine Rescue Center. They showed us turtles, manta rays, and seals. They took us through the process of rescuing a marine animal and how they perform a physical before bringing them in. After a period of treatment usually they come to the conclusion on whether or not an animal is qualified for release. At the Rescue center, they have Chestnut, a green turtle there that is unreleasable. Due to the injuries caused by a recent boat accident, her shell grows more upward, inducing air pockets that cause imbalances during movement. Because of this, her home will remain in centers as such for the rest of her life.

Unfortunately not all animals are as lucky, if they are unable to find a forever home for animals such as one of the blind seals they had. They are resorted to being euthanized because they cannot be released under those conditions. This is normally the most ethical way to deliver a “good death” for marine reptiles/cetaceans/pinnipeds.

If animals are releasable, Rescue Centers usually take certain precautionary measures around these animals. There is usually no talking and minimal human contact to ensure these factors don’t make re-release more difficult/stressful.

|

| NY Rescue center Biologist feeds Chestnut (green sea turtle) Romaine lettuce. Chestnut floating her way over to some delicious lettuce |

Why euthanize them? You may ask, Are there no other options? Usually there aren’t, Euthanization is the fastest, humane option for marine mammals. Upon evaluation by a veterinarian the euthanization of unreleasable animals allows rescue centers to use their carcasses for research. From this stems a better understanding of these animals which may lead to better treatments in the future.

|

||

| Device used to keep Chestnut afloat, due to her injuries. One side of her shell is more buoyant than the other. |

The fingerprints of climate change can be seen all over our planet. Our warming ocean has caused worsting storms, bleached coral, and has had a strong impact on our glaciers, melting thing, causing climate change to worsen. However warming oceans has caused more damage the closer you look. Warmer oceans cause more tropical species to migrate to seasonal waters, only to die off if they don’t move back to tropical waters come winter. In a similar aspect, animals that migrate south for the winter now must adapt to waters colling down sooner. Sea turtles and other cold-blooded animals are often the victim of this “cold stun”. This phenomenon is called cold stun because as the environment gets colder their metabolism slows down, and eventually they’ll lose the energy to move, eat, and can die from this.

Here you can see Chesnutt’s flotation device as she swims towards the camera.

Riverhead Marine Rescue Center

by Ed LeMoine

On our trip to Riverhead, our main destination was the New York Marine Rescue Center located inside the Riverhead aquarium. The Rescue Center was first opened in 1966 and remains the largest marine rescue facility from Virginia to Maine coastwise. Maxine Montello, the director of the Rescue Program was kind enough to show us through all the facilities. While the aquarium itself is for-profit, the rescue center is a non-profit that works with volunteers and the community to find and hopefully rehabilitate turtles, seals, and other select pinnipeds and cetaceans. “Why is a Marine Rescue center necessary?” some may ask, and to them I’d ask if they would know what to do with a usually large, possibly irate sea creature on the beach before them. As mentioned, the rescue center works with the community to deal with situations akin to this.

MAR 355 – Sag Harbor Whaling Museum & Custom House, Sept 17, 2021

Art Imitates Life in a Whaley Interesting Way

by Clare Dana

I’m sure most of us have heard the saying “art imitates life” which is the observation of creative work that has been inspired by true events based on a story. While walking through the whaling museum, the art depicting the culture of whaling is clearly evident from portraits, figurines, and statues. Art is one of the main platforms to learn about a specific culture, and the use of whaling themes and whale parts in much of the art highlights how influential whaling was in defining the culture of Sag Harbor and much of New England.

|

| Image 1: These are some of the scrimshaw pieces on display at the museum. You can see the images of both sailing and the action of hunting the whale. |

Harpoons evolved over time to be more reliable in its ability to remain in the whale. The number of harpoon’s barbs, called flue, was reduced from two to one because the narrower head allowed for deeper penetration; whereas the two-flue harpoon did not go deep and most likely fell out of the whale, the one-flue harpoon more often went deep enough to pass the layer of blubber. The toggle harpoons were used by the Native American tribes before the whalers started using them. The rotating head or the toggle head would rotate 90° to almost guarantee that the harpoon would get stuck in the whale but the early version had a difficult time preparing the harpoon. A grommet, likely a strap or metal ring, was used to hold the harpoon’s head in place so it could pierce the whale but the harpoon would often dislodge before it could properly set in the whale’s body. Later toggle harpoons were improved and made by Lewis Temple, an African American blacksmith, and were vastly superior because the toggle mechanism was contained within the harpoon head itself rather than an external component.

Real Recyclers: 17,18, and 19th Century Long Islanders

by Molly Showers

The Whaling Museum and Greek Revival

The Old Whalers’ Church and Egyptian Revival

by Mathew Amoedo

This is a photo of a sugar cone and a marble paperweight. The paperweight speaks for itself but the sugar cone I found to be interesting. Sugar was transported in that conical shape and was often so hard that one would need a tool like a hammer to break the sugar up, as sugar cubes were not popularized until the late 1800s.

This is a Certificate of Enrollment. This would be used as Americans to prove to the British that they were trading with that they were actually Americans. As you could imagine, they did not work very often.

You may notice something interesting about this clock. They actually had to raise the ceiling to accommodate for the sheer height of the clock. Its height and extravagance no doubt symbolized wealth and class.

This cane was made from the vertebrae of a shark. A cane back then was not always used out of necessity. It also represented class and wealth.

This may just look like a normal chair, but it is actually quite expensive. It was made from mahogany, which again would be a sign of wealth and status. This type of chair would be referred to as a great chair due to the fact that it has arms.

Life in the Customs House

by Amanda Tepper

The Sag Harbor customs house has a rich history, for not only was it the office of Henry Paker Dering but it was also his home where his family lived and his children were raised. Getting a tour of the Dering home gave special insights into how a household was run in the late 1700s that you could not truly get in a classroom. Even though the Dering family was well off financially, this peek into Henry Paker Dering’s, his wife Anna Dering’s, and their nine children’s lives also shows how many other people lived during this time.

One part of the tour that truly stood out to me was the kitchen. Standing in the kitchen you can instantly see the absence of basically all the appliances that we have in our modern kitchens. Now you may be sitting there thinking, “well of course not, it’s the 1700s”, however seeing the kitchen in person helps to give a perspective on how much more work had to go into sustaining a family during this time. The only way of cooking something was by using a fireplace, and the only way to bake something was to take coals into a sealed off stone cubby with dough and then carefully monitor it since they lacked the modern comforts of setting an oven to a specific temperature and starting a timer. The kitchen had no running water, thus time and energy were spent daily to go to a pump and collect some. The closest thing to a refrigerator was a “pie safe” which was just a cabinet that kept flies off food. However, all this being said about how much work keeping the kitchen running alone, the Dering’s did have enslaved people and indentured servants, so household chores were not the sole weight for Anna Dering to bear. Nevertheless, many families in this era had similar setups which just makes you think about how much time every day was put into simply keeping a household running. In the end I couldn’t help but feel thankful for the luxury of our modern technology.

MAR 355 – Kayaking in North Sea, Sept 10, 2021

Windy Kayak Adventure

by Lucas Chen

We took off for the kayak trip. The winds were blowing southwest at about 16 kts, but if felt more like 20 kts. The white caps were tough to maneuver in. First we went to Alewife Creek, Conscience Point, and then the beach.

This was at Alewife Creek. Kurt lectured about alewives that migrate through here in the spring to Big Fresh Pond to breed, and then migrate back to the sea at the end of the summer. We also learned about the ospreys that come to Long Island every summer to breed. They come back to the same mate every year and lay about 3-5 eggs a pair.

Pictured here is one of the oyster farms in the North Sea. This was right next to Conscience Point. The oysters are raised here in bags and sold when they reach size. They start out as seeds by the docks where we took off with the kayaks. They must be flipped to prevent biofouling from accumulating. It also helps create a typical bowl shape, which is what makes them more desirable to consume.

The Iconic Big Duck

For this week’s Friday trip, we all went out to Conscience Bay for a kayak day with a couple lectures on the water! One of the places we stopped for a lecture was by a duck blind, where our discussion on ducks began. The discussion drifted from hunters using duck blinds to conceal themselves when hunting to an iconic landmark on Long Island, the Big Duck! We learned that the Big Duck located in Flanders, LI was built in 1931 by Martin Maurer, a duck farmer. Maurer sold ducks and eggs from the shop located inside the Big Duck. It was built with the intention to attract drivers and vacationers traveling down the highway, hoping to encourage them to stop in.

The Big Duck is a symbol of architectural brilliance as well; moved by Maurer’s creation, architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown coined the architectural term “duck” to describe structures that plainly display their function or selling product in the design of the building itself — Maurer’s Big Duck, a building that is in the shape of a duck, was built to sell ducks and duck eggs. If a building is not considered a duck, it is said to be a “decorated shed” — a plain building which relies on an external symbol or ornament (like a sign) to convey its function. Today, the duck and decorated shed theory is taught in architecture courses as a revolutionary way of classifying buildings, and the theory can be traced back to Long Island’s Big Duck.

Here is a picture from a couple weeks ago of me, Nikole, and Clare when we stumbled upon the Big Duck on our day adventure in Riverhead. Sure enough, the Big Duck entices passersby to stop and visit — we did! Unfortunately, we missed the gift shop visiting hours by a half hour, but we decided we would have to come again to explore the gift shop.

Kayaking Trip

by Samantha Aplin

Everyone either hates or loves ghost stories, but our class was thrilled when Dr. Rider and Dr. Bretsch told us that after we filled up on chili and brownies at the marine science center, that they would give us a walking ghost tour of campus. This included the historic windmill on campus, and a few of us had heard that it was haunted. We were thrilled to finally learn if the rumors were true. We all climbed up a hill to get to the windmill and gathered around Dr. Rider to listen to her ghost stories.

This windmill, pictured below, Dr. Rider said was originally in the village of Southampton, but as more people arrived in the village, they needed more room. They were going to tear it down, but instead a woman that initially owned the land that the Southampton campus is on, said it was an important part of the history of the town and she wanted to keep it. They moved the windmill onto the property and turned it into a playhouse for their daughter. Their daughter became friends with the fishermen that would bring fish to her family, and as her playhouse on top of a hill, it could be seen from the bay as well as the ocean. On foggy nights, she would light a candle in the window of the windmill so the fishermen could find their way home. Unfortunately, she dies at the age of 10 due to tuberculosis, and while her family left the estate as there are too many memories there, rumors say that she stayed on campus with us. On a foggy night, you can look up into the window and still see a candle burning. When Dr. Rider said this, the lights around the pathway up to the windmill turned on and I got chills. This was the only rumor that I had heard of about the campus being haunted, so I did not know about the other ghost we have on campus.

Dr. Rider said that after the original family left, other families had owned it until LIU bought the land for their Southampton campus. This campus became well known for its marine biology department, much like it is now, but other than that, most of the students went to the main LIU campus. However, there were still enough student at Southampton LIU to have fraternities and sororities, that engaged in hazing. One fraternity in particular thought it would be a good idea to tied down a guy from Greenport to the blade of the windmill and have it turn. Unfortunately, he did not survive, and Dr. Rider said that if you ever feel a cool breeze walking through the trees on campus, it’s just him trying to get back home. Once Dr. Rider finished her statement, Dr. Bretsch jumped out from the trees and screamed. Half of the class had their backs facing him, including me, and he scared me so bad I just sat on the ground shaking in fear. It was overall a night I will never forget.

West Robins Oyster Farm

Oysters are a very valuable bivalve that lives in our local waters here on Long Island. Not only do they contribute to our region’s most valuable commercial fisheries, oysters also clean our waters and offer food and habitat to many animals. As filter feeders, oysters serve as a natural water filter where they can filter through and trap nutrients and sediments in around 50 gallons of water per day, which greatly improves water quality. With clearer water, more seagrasses can be supported, bringing an increase in oxygen levels. Oysters also create oyster reefs as they have a tendency to attach themselves to hard substrate or other oysters. Oyster reefs can then provide habitat for organisms such as fish and crabs.

Overharvesting, disease, and habitat loss have brought a significant decline in oyster populations, bringing many negative environmental impacts. Many companies and organizations in Long Island are making efforts to increase oyster population numbers and reverse these effects. During our kayak trip, we traveled through North Sea Harbor which contains West Robins Oyster Farm: an oyster farm aiming to increase oyster numbers through sustainable methods. Oyster farming is an aquaculture practice where oysters are bred and raised, not only to sell as food for humans, but also to improve water quality. West Robins Oyster Farm does not harvest wild oysters or seed from open fisheries on Long Island, which promotes raising population numbers instead of dropping them.

Not only do oyster farms provide oysters for our consumption in a sustainable way, they also provide many positive environmental effects. Harvesting the bivalves loosens and disperses sediment which improves the overall sediment quality, as well as adds oxygen to the lower waters and sediment. It is so important to bring back our oysters here on Long Island, and it is so great to see places such as West Robins Oyster Farm who are making the proper efforts to do so.

|

| This image shows oysters that have attached to other oysters or oyster shells, creating an oyster reef. This oyster reef has created space for an Asian Shore Crab to hide in from predators. |

|

| This image shows the cages of West Robins Oyster Farm. The oysters are suspended near the surface of the water in each cage. Here, their energy is focused on shell growth. |

Kayaking Trip

When thinking about wildlife, and how we treat it nowadays, it is hard to avoid the one little question: “should we preserve, or conserve? Sustain or let it all rot in vain?” “But wait!” You might cry before we can even try, “How are the three even different?! To Preserve, to conserve, or to sustain?” To answer such a question, I must recall a certain quotation, an interesting little point, something I learned past Friday at North Sea Harbor of Conscious Point.

The idea of preservation is perhaps the most simple. “Don’t touch nature! Do not pinch or even tickle. Leave it as it is now, with the only objective being: “Protect what we have left! Stop any new development or usage by any human being.”

Conservation, on the other hand, has a bit more leeway. “You may use the resources here!” They say, ah such music to my ears. But don’t go crazy, like any good deal, there’s a little caveat. The resources must be used, to not only aid you, but the maximum amount of people, the biggest bang for our nature buck. But take care, and beware, you must not snooze. After all, no matter how wisely you use your resources, it will run out one day, which will be terrible news.

Finally, sustainability! The 21st century’s modern trend, “it should be fine to take from nature, if in turn we help it mend.” This might be considered conservation but better. We take what we need and leave the rest for later. And while we leave and are enjoying our catch, we also help mother nature’s wounds patch. Planting trees, releasing fry, limiting hunting and fishing. We give back to nature what we used in our apple pie.

Fish Cove in Southampton

A shot of the Fish Cove I took while the class was instructed to get our kayaks in line. I found the most difficult part to be the spacing and avoiding the foliage along the coast, which is visible on the adjacent coastline in the photo.

This shot shows a wide shot of Fish Cove along with the bridge on Noyac Road we had to cross under. The wind made this task quite difficult, as the waves pushed the kayaks around like they were driftwood.

Once we had gotten ourselves situated in a suitable formation on the kayaks, Kurt gave a lecture on some of the local wildlife. Most notably we talked about ospreys, also known as fish hawks. Contrary to their nickname, they are not hawks, but raptors. During the colder months, they migrate as far south as the Amazon Basin in South America. Their peak migration time is in early October. They are also monogamous birds, meaning they pair for life, but they frequently separate during these migratory seasons. Unfortunately, osprey populations declined due to the use of harmful pesticides like DBT in the 60s. This was especially harmful due to the biomagnification and bioaccumulation of the pesticides as they moved through different organisms up the trophic levels. The pesticides would affect the thickness of the osprey’s eggshells, making them thin enough to where they would crack under the parent osprey’s weight. Luckily, the use of DBT was outlawed in the 1970s, so we are still able to enjoy the presence of this magnificent bird today.

MAR 355 – Tiana Beach, Shinnecock Inlet, & Rogers Mansion, Aug 3, 2021

Community efforts are large driving force in conservation. In this week’s trip we were able to observe a great example of community efforts to regrow a population. As a class, we headed over to Tiana beach and pavilion in Southampton. Across from the beach is the bayside, decorated with a large whale tail made from recycled waste. In the water were rows of partly submerged oyster cages. The cages were attached to a floating dock using various ropes and floatation devices. In these cages the oysters are protected from predators such as American oyster drills and Asian shore crabs.

A Walk Through History at Southampton’s History Museum

His whaling trips allowed him to bring back souvenirs that would fill the home with some of the history that we can still see today, such as the collection of fine china on the right.

Samuel Parrish was a successful lawyer with an interest in the arts. In fact, he established the Parrish Arts Museum to display his collection of art. He had an interest in the art of Italian Renaissance, pictured here with his collection of plaster copies of medals depicting Roman emperors and French rulers. I was surprised to learn that Parrish was actually the mayor of Southampton for a term. He initially purchased the Rogers Mansion as a summer home, but it seems the town became something dear to him. He invested a great deal into the town, hiring a company to liven up Main Street’s commercial aspect, establishing the Parrish Museum, and helping establish the Southampton Hospital and Rogers Memorial Library.

This past week, we visited the Southampton Historical Museum and one of the first things I noticed were the women’s clothing on display. These everyday outfits were extravagant by today’s standards. Women were covered from head to toe, even in the privacy of their own homes. We view these dresses as restrictive and appropriating, but these were simply the style of the time period. Beauty standards have been changing since the dawn of society, and there are always several different standards men and women want to abide by. In the Victorian era, corsets are the piece of clothing we picture the most. Corsets squeeze the waist, accentuating a woman’s bust and hips. This was desirable as a show of child bearing and motherhood.

Southampton was, and is still today, a town of wealth. Clothing has always been a part of demonstrating that wealth to the public. Hats were a simple way to present a woman’s money. The more fanciful the hat, the more money it is implied the owner has. Hats were also a way to announce the marital status of a woman. Clothing was exceedingly important to the women of the Victorian era, as their reputations were dependent on the way they presented themselves. History is fascinating in many ways, but the Victorian era seems to capture our attention the most, particularly with the common styles of the time.

Southampton/Hampton Bays Orientation: Agawam Lake, Ponquogue, & Tiana

by Asher Novkov-Bloom

Other necessaries at the Rogers Mansion Museum complex include a barn, a decoy shed (used for carved duck decoys), a schoolhouse, and an outhouse. While not all of these were original to the property, all are original to the time period and similar structures likely existed on the property. These necessaries gave the wealthy homeowners access to services and resources right in their backyard, while less well-off families would have to share communal facilities or simply go without some services. When people think of historic estates, they rarely think about the necessaries surrounding the main house. That being said, these necessaries can be a unique look into what the upper classes considered essential to everyday life.

The Trustees of Southampton

by Ed LeMoine

If you live in the Southampton area, you should be all too well informed on trustees as they campaign to and are elected by the public. Trustees work with the mission of managing common land for common use and can in some cases overturn the decisions of local government in towns. Trustees can overturn local government on occasion if they feel that the decision(s) being made are not in the best interest of the town, primarily regarding land. This can and has unfortunately led to corruption as a position with this much power is likely sought after by people with deep pockets. However, the ideal trustee works to preserve the land of Southampton for many to enjoy.

MAR 355 – Shinnecock and Peconic Bay Tour, Aug 21 2021

Coastal Cultural Experience Explores Canoes and Canals

by Molly Showers

As a welcome into the Coastal Cultural Experience, we toured around the Shinnecock and Peconic Bays. The two are connected through a canal that was constructed in the late 17th century. Before that point, the local Native American tribes in the area, such as the Shinnecock (and possibly the Montaukets, who were nearby) would have to lug their canoes from the Shinnecock Bay to the Peconic Bay. Over time, they had cleared a path, which is where the canal would be placed in 1690, fifty years after the English settlers would first arrive on Long Island to form Southampton.

As we traveled into the canal from Shinnecock Bay (Image 1), I found it surprisingly easy to forget about the heat and humidity from the 90° day and imagine the settlers and Native Americans alike traveling from one bay to another. Although it is just a glorified man-made ditch, it is valuable for travel and economic purposes. For example, fishermen in the Peconic Bay (Image 2) have access to the Atlantic and Native Americans could reach other tribes in the North much easier. It was interesting to think about just how many people have used this canal for the hundreds of years it has existed (Image 3). Such a simple idea of a ditch has had a revolutionary impact in the area of Southampton.

From a scientific standpoint, I found this canal to be a marvel as well. As someone who is much more accustomed to freshwater canals, since I am from Upstate New York, I had never taken the time to think about the impacts of canals in saltwater systems. I just had assumed that water simply moved from one section to another, accounting for the differences in depth. However, I learned that there is a tangible difference in salinity between the two bays, with the Shinnecock Bay being saltier than the Peconic Bay. To move boats through the canal without too much damage from the different salinity levels, water can only flow from the Peconic Bay to the Shinnecock Bay.

Just from this one canal, I had learned so much about Long Island’s history and ecology. Perhaps during my Semester by the Sea, I should take a small trip to the canal and fish along it’s edges, basking in its historical significance.

Image 1: This is Shinnecock Bay, which faces the Atlantic Ocean. This is important for the placement of the canal, since the fishermen and other baymen could have direct access to the ocean for their industries. The coast of Shinnecock Bay housed the Shinnecock Native Americans as well. This phenomenon of naming places and towns after Native American tribes and important figures is common on Long Island, I have come to find out.

Image 2: This is Peconic Bay, which resides in between the North Fork and South Fork of Long Island. Since this houses the mouth of the Peconic River, this water is much fresher than the Shinnecock Bay. We sat along the jetty of the Peconic Bay, which was erected to stop the longshore drift of sand westward through the bay.

Image 3: This is the canal that connects the Shinnecock Bay and the Peconic Bays. It was very cool to see the water change in the canal lock as the level evened out to the bay in which we were entering. In this picture, one can see the Peconic Bay.

The Geographical Effects of The Great Hurricane of 1938

The opening of this inlet was not all positives, as you might imagine. In order to stabilize inlets, the use of jetties is commonly employed. This is exactly what was done at Shinnecock Inlet, but a problem is introduced when considering natural coastal erosion. Due to the angle at which water flows into the southern shore of Long Island, sand is gradually moved from east to west. This is called longshore drift. If an inlet is created, it becomes a sand trap, pulling in sand that was meant to continue its journey west. This opening had another non-obvious consequence: weaker water flow in another inlet further west called Moriches Inlet. This weaker water pressure induced the building of more jetties, further inhibiting longshore currents. All this culminating in rapid erosion of beaches west of Moriches Inlet that would have been naturally replaced by sediment moving from the east to the west due to longshore drift.

I think the takeaway from the eighty-three years since The Great Hurricane is that humans cannot control nature on as great a scale as we might like to think. People decided to find a silver lining in the hurricane the destroyed their homes by making a faster route from Shinnecock Bay to the Atlantic Ocean, however, we are ending up paying for it with the homes and habitats of those to our west.

Ed LeMoine

Coastal Cultural Experience: NY Marine Rescue Center & Peconic River Fish Ladders

The Use of Satellite Tags in Tracking Sea Turtles

by Ana Noel

The NY Marine Rescue Center uses methods to keep tabs on their animals after they are released. One way they do this is with flipper tags. These are tags that are inserted in the flippers of the sea turtles and seals after they release them with their organization name and number. This allows for them to keep track of the animal if it were to return to shore. For example, if someone found this animal and called the number, they would be able to get the location of the animal as well as know that the animal is still alive after they released it.

Another tracking device they use is satellite tags. These are placed on the shell of the sea turtle and connected to a satellite. The satellite connects to a computer to show not only where the sea turtle is located currently, but also the path it took and the places it was before. This is beneficial because it allows the sea turtle to be monitored. This can help show if the sea turtles are displaying normal behavior by looking if they are migrating at the appropriate time. This can also help show if the sea turtle is still in the colder waters and gives them an idea if this turtle may need to be rescued again because of cold stunning. In addition, these tags can help show if the animal survives after they release them to see if their efforts to save them are working. A problem with this technique is that the tags are expensive ($1000-2000) and can fall off since they are located on the outside of the turtle’s shell.

Diagram of how satellite tags work from the satellite to the computer.

Location of five sea turtles that were released from the New York Marine Rescue Center. This is an example of how satellite tags work by being able to track the turtle’s location since their release.

Satellite tags attached to a turtle and the different examples of satellite tags used. These tags are not only used to locate the turtle, but also to collect the temperature and dive data of the turtle to see if the turtle may be experiencing cold stunning.

Example of data collected on the dive depth of the Atlantic green sea turtle with the use of satellite tags.

The New York Marine Rescue Center with Connection to Pinniped Stranding

by Mateo Rivera

Pinnipeds, which consist of seals, sea lions and walruses, are highly susceptible of becoming stranded on beaches along the East and West Coast. These strandings are caused by a multitude of reasons, but the most common are from fishing gear entanglements, boat strikes, and starvation. The factos that lead the mammals landing on these beaches can lead to their ultimate deaths. It is crucial that the information gathered be reported to NOAA so response and tratment methods can be improved. Also, it can support in educating the community and preventing fisheries from making fatal mistakes that can result in increased strandings. The pinnipeds in the pictures are from the Long Island Aquarium, NY and are represented by harbor seals and grey seals. They are extremely playful as you can witness by the picture on the right as they glide through the water in the enclosure.

The New York Marine Rescue Center is the only location that services these stranded organisms in the state and is stationed in Riverhead. Their effort is crucial to addressing these events and facilitating their rehabilitation. This part of the rescue center is known as “seal row” and it consisting of 16 tanks for holding small seals. Keeping them in an area where they are able to heal and in the water is important so that their recovery occurs rapidly. They are kept at a constant temperature and salinity, since the saltwater is apparently good for healing. Water quality is checked and maintained every single day. However, seals haven’t been stranded recently so they are adapting this part of the center for large loggerhead sea turtles.

NY Marine Rescue Center

by Sandra Reyes

During the trip to the New York Marine Rescue Center we learned a lot about the animals that they can care for and how small things we do can help reduce the number of animals they have to rescue. They are a nonprofit organization that helps rehabilitate, release and relocate marine animals that get entangled or need medical assistance. They are the only respondents for cetaceans, pinnipeds and sea turtles for the whole state of New York. They even have 3 volunteer veterinarians on call; two of which I have had the privilege to meet, Doctor Rob and Doctor Jen (Doctor Jen loves Stony Brook students because she is a Stony Brook graduate).

During the months of late October to mid-January is referred to as “cold stunt season” and since we are currently in that season Maxine Montello was telling all about it. The cold stunt season effects the sea turtles; and besides boat crashes, entanglements, and fish hook mishaps, it’s what brings in the most sea turtles. When a cold stunt sea turtle is called in the first thing that they do (as well as to any animal that is brought into the hospital) is give them a full physical. The physical includes x-ray scans, physical touch for reflexes as well as abnormalities and even blood work.

Figure 1. Maxine Montello displays two x-rays (one of a loggerhead sea turtle and one of a seal pup), talking about the x-ray procedure for each animal.

After they get a physical, they are categorized into one of four classes depending on the severity of their condition. There are four different types of sea turtles; the Atlantic green, the Loggerhead, Kemp’s Ridley and the Leatherback sea turtles. Out of the four the leatherback is the largest and the only sea turtle said to not be affected by the cold stunt; therefore, the other three take up most of their rescue calls. Class one cases are usually if they are still alert and have normal reflexes and class four means they have to responses and can’t even breath on their own. Once the turtles have had a full exam they want to warm them up to 15°C but very slowly (2-3 degrees per day) to make sure not to cause internal body damage. They go through a critical five-day intensive care protocol in which they are not left in the pools alone overnight and kept in a room that matches their internal body temperature. They say that the first 48 hours are the hardest and that if they survive past day 3 that they usually don’t have to worry too much after that.

Figure 2. This image displays the posters that the staff reference when trying to place a turtle in one of the four classes. The poster on the bottom helps the staff know what to look for in specifically a Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle.

Once they have made it past the five days they are usually in the clear, however, they are still not permitted to stay in the pools overnight unless they can swim stably on their own. This includes being able to lift their heads above the water, swim to the bottom and back up, and interact in a non-threatening way with the enrichment around them. They must maintain the pools to make sure that they stay at the turtle’s body temperature as well as a constant 32 ppt in terms of salinity. After the turtles pass their physical exam and the five-day mark, they get charted and all their information gets sent to NOWA to be determined if they are releasable or not. Unfortunately, once the cold stunt patients are deemed releasable, they can’t be released here due to the cold weather, so they usually stay “in house” with them until the warmer weather comes back. If they have a large amount of them, they will partner up with a team in Florida so that they drive them to Boston and the other team drive them straight to Florida to be released there.

Figure 3. This is turtle 90, a baby Atlantic Green sea turtle who had been affected by the cold stunt and brought to the rescue center for a week ago. 90 is doing very well, and will have her first overnight in the pool soon

Deadliest Predator in the Ocean

by Katelyn Castler

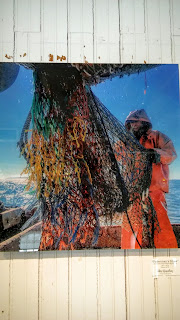

The Riverhead NY Marine Rescue Center focuses on helping strained marine mammals and sea turtles. The biggest problem that these workers noticed the marine life have been facing is entanglement issues with nets or other marine debris. They provide a hazard as they may prevent an animal from feeding, limit movements, or even cause deadly wounds or infections. Once these animals face a problem like this, they can then become even more susceptible to other predators or ship strikes. The issue these marine mammals or sea turtles face is considered one of the top known human-caused mortality events. It is very dangerous and has become a serious problem today.

Figure 1. Image of nets/line that have or may cause marine mammal or sea turtle entanglements.

There are many ways to help prevent these entanglement issues. One way is to clean up after yourself. No matter where you are in the world, all the surrounding water ways are connected to the ocean. By picking up your trash, plastic bags, straws, ect. you are helping to prevent unneeded material from going into the ocean. Another way to help is to be cautious of your surroundings. If you are out fishing, be on the look out for protected marine mammals or sea turtles. Also be cautious of where you are putting line out and what you might be expected to catch. Lastly, spread the knowledge to your friends and family. The best way to protect marine life is to make everyone knowledgeable about the issue at hand so everyone can contribute to the protection. The more people who want to protect our oceans, the cleaner and safer it will be for marine life.

Permanent residents of the Long Island Aquarium

by Arthur Cody

During our trip to Long Island Aquarium and the New York marine Research Center, we saw a number of permanent residents to the aquarium and research center. The exhibit housed harbor seals and one gray seal by the name of Gray beauty. Gray Beauty was blind from cataracts in both her eyes and was rescued By New York Marine Rescue Center.

Other residents of the aquarium are the skates and rays that live in the display at the front of the aquarium. While we were there we saw a small baby in the tank and were informed not to touch it as it is very fragile as it was only recently born.

Another resident of the aquarium inside of the New York Marine Rescue Center is chestnut the Atlantic green Sea Turtle, housed within one of the tanks used by the rescue center for seals. Chestnut was struck by a boat that damaged its shell, the shell then began to reform. But instead of growing out throughout the entire shell, the shells carapace grew up, and this means that Chestnut was now top heavy and was more buoyant, which means he would never survive out in the wild. Overall, the trip showed us how these permanent residents rely on facilities like these to survive.

The History of Riverhead’s Alewife Ladder

by Charlotte Brennan

The Peconic River is an estuary meaning that there’s a mixture of salt and freshwater within the same body of water. The brackish water flows east and there’s saltier water on the bottom. As a result of this, there are brackish species within the river, including alewives, a species of fish. However, many estuaries are in trouble due to increased development around them. This affects migratory species such as alewives and American eels.

Within the Peconic River, alewives weren’t able to get over drops which endangers their ability to spawn and survive as a species. The population of Peconic alewives has plummeted since colonialism because we blocked their path within the river. In order to solve this problem, Bob Conklin developed a metal shoot in the early 2000s to place in the water to help the fish swim. However, while it worked okay, leaves would clog within the shoot and it required too much maintenance.

In 2010, a new natural slope, similar to a creek, was built within the river to replace the old shoot. It also includes rocks that helped slow water. Unfortunately, Bob Conklin died before it was put in, but the project has been a success for alewives and has helped their population. There is also a deep 12ft pool close to the ladder where 5000 alewives lay their eggs.

This is an example of signs that are posted all along the Peconic River where alewives live in order to protect their species and keep them away from further harm.

This is a rock located within the park dedicated to Bob Conklin who originally designed the fish ladder but wasn’t around to see the final form unveiled.

Here’s the alewife ladder in its full glory. To the untrained eye, it looks like a normal creek, but it actually is manmade and helps alewives greatly.

Right where the alewife ladder is, there’s an indentation in the concrete where an old gate used to be located that has since been removed to make way for the alewife ladder.

Attention to Detail

by Kristi Flanigan

When we visited the NY Marine Rescue Center, the first critters we encountered were the seals outside, swimming peaceably in their enclosure. Inside, there was a touch tank comprised mostly of stingrays. Past then, and all of this before our tour even began, we saw fish. One of my favorite things about aquariums is how much information is everywhere if you can drag your eyes away from the animals long enough to read it. Now starting to contain my excitement enough to take notice of the posted signs, I read up on the Gulf Stream and how it affects fish distributions while we were given time to look around pre-tour. Gulf Stream riders are tropical fish that are carried, as the name suggests, by the Gulf Stream, which can transport them hundreds of miles away from the warm southern waters we most immediately associate them with. It’s such an impossibly massive thing to imagine, watching the fish in the tank wind their way through the water so serenely, that in the wild they could see hundreds of miles of ocean in their lifetime. The vastness and complexity of so many small lives is certainly not something I’m really able to fathom even when I look out at the ocean. I kind of hope I’ll never lose that sense of wonder.

Speaking of a sense of wonder, we move from the main part of the aquarium into the repurposed warehouse that is the animal hospital for our tour, and I find it worth reflecting on that I’m passing through a space that makes a constant impact on the health of various types of marine life. In such a short time span I’ve walked past seals, fish, and turtles, and was we stand in front of the rows of tanks, we learn about why dolphins are not present and are never present inside the NY Marine Rescue Center. The reason? Viral disease. It’s a different kind of detail not exactly visible or easily fathomed, especially looking at the up-to-code cleanliness of the animal hospital. But that’s what happened – a highly contagious and airborne disease was becoming an issue in local waters to an uncontrollable degree and the facility happened to test positive. It could have spread to other animals in the facility, so for the safety of the animals the facility complied with regulations and no longer houses dolphins. It’s the kind of information I find hard to believe, even saddening – a place so dedicated to the care of their animals, so committed to the health of marine life, simply unlucky enough to lose an invisible fight against microbes. That said, and very much so to the facility’s credit, they have been able to move forward and help more sea turtles, in particular, than ever, and are doing so wonderfully. While we’re there we see a sea turtle finally go to the bottom of its tank on its own. The viral disease situation might be called a setback, but the center has moved forward to make an in-house impact where it can. It’s that attention to detail and love for the ocean that I really enjoy and respect. Aquariums and rescue centers for marine life are truly inspiring, fulfilling places in the face of the challenges inherent in caring for the world’s oceans.

Estuaries (Riverhead)

by Tyler Rodriguez

The above image is from an estuary in Riverhead, New York. An estuary is a semi-enclosed body of water where saltwater and freshwater meet. This type of mixed water is known as brackish water. Estuaries are a unique environment that are home to a large and diverse set of wildlife, including fish such as alewifes and birds such as seagulls and ducks. Because of the influence of tides and freshwater rivers draining into saltwater, these areas are rich in nutrients and contribute to a very productive ecosystem. The below image is of Mallards that live in the estuary area in Riverhead.

Estuaries have been important to coastal communities for hundreds of years. Early coastal communities realized the benefit of these areas and many harbors were developed in estuary regions. Because they are semi-enclosed, they are generally protected from ocean hazards such as large waves from storms. The very nature of estuaries provide protection to boats and harbors that development at the open ocean would not. As we have seen in past trips for this class, many harbors and maritime points of significance (such as the launching point for trans-Long Island Sound ferries) are in protected areas. Estuaries, historically, have been the perfect location for coastal development.

The Atlantic Green Sea Turtle #90: on the way to Recovery

by Joanna Zhu

During our visit to the New York Marine Rescue Center, we saw three cold-stunned sea turtles in rehabilitation. All three were rescued on Saturday, November 9th, 2019; one of them is a loggerhead and the other two are both Atlantic green sea turtles. The Atlantic greens are given the numbers 90 and 91 in order to identify them. #90 was discovered in Southampton by the founder of Tate’s house, in front of her house. It is the tiniest Atlantic green sea turtle the facility had ever rehabbed; this species is the largest hard-shelled sea turtle species so it can potentially grow very large.

We were very lucky to witness #90 diving, which indicated it was recovering from cold stunning. It was swimming slowly on the surface of the tank when we just arrived. It was very weak when it arrived at the rescue center, classified as a type III, meaning that it could respond to touching but with shallow breathing. According to Maxine Montello, the director of the rescue program, #90 cannot dive yet. However, after a few minutes we were all surprised to see #90 repeatedly diving slowly to the bottom and swimming up to the surface to breathe.

Photo 1: #90 when we first arrived, floating on the surface with heads raised above water (©NY Marine Rescue Center).

Photo 2: #90 slowly diving to the bottom of the tank (©NY Marine Rescue Center).

From #90, we can see the efforts the rescue team putted into rehabilitating these animals. Before #90 can dive, it was in a critical period and could not be left in the tank alone overnight. One team member was needed every night to watch over it before it can dive. Also, the tanks were decorated with red ribbons to help with recovery. These ribbons were imitating kelps in which juvenile sea turtles like to hang around for protection. We frequently saw #90 swim around and under them. Now that #90 can dive on its own, it is showing great signs of recovery and increase in strength. We hope that all cold stunned sea turtles in the facility can be successfully rehabbed and released back to the ocean!

[Photo 3] Photo 3: #90 swimming and floating below red ribbon which imitates kelp (©NY Marine Rescue Center).

Coastal Cultural Experience: Mystic Seaport

The Living Experience on The Charles W. Morgan, America’s Oldest Commercial Ship

by Tiffany Cui

During our trip to Mystic Seaport, we boarded The Charles W. Morgan, a 124-foot-long whaleship built in 1841 and the oldest commercial ship still afloat in America. While on the ship, we were guided below deck and shown the living quarters of the crewmates.