Still from “Heaven,” by Troye Sivan

In my blog post on All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely, I noted “the talk” as a form of cultural inheritance that reveals how many black parents instruct their children to respond when confronted by the police.1 “The talk” appeared again in Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, and while this is an extremely unfortunate instance of cultural inheritance, it has led me to inquire how other communities explored in the frameworks of this course might enact similar exchanges.2

While disability and LGBTQ+ communities may have some genetic components, they are—by and large—disconnected from the type of biological lineage one finds in racial identities. Yet, YA literature frequently treats older characters as guides for the younger protagonists. This is certainly the case in Neal Shusterman’s Challenger Deep as 14-year-old Caden interacts with his therapy group leader, Carlyle, who has also been diagnosed as schizoaffective. From Carlyle, Caden learns that mental illness is “a long voyage, [but] it doesn’t mean you’re on it forever.”3

As we question how queer communities continue this intergenerational model, however, we are interrupted by queer theorists who resist preexisting ideas of community. Expanding on the work of Leo Bersani, Jack Halberstam states that the whole idea of a “gay community” is “complete fiction”: “[T]here’s nothing really that unites gay people, and, furthermore, there’s nothing necessarily that orients gay people to progressive or radical politics.”4 While this stance offers an explanation to an intergenerational resistance in queer theory, it does little to account for the fact that there are, indeed, many queer people in existence, and that they have, at least linguistically, been lumped together. Whether this group is better termed a queer population or a queer community, there are, nevertheless, aspects of cultural inheritance that do unite them.

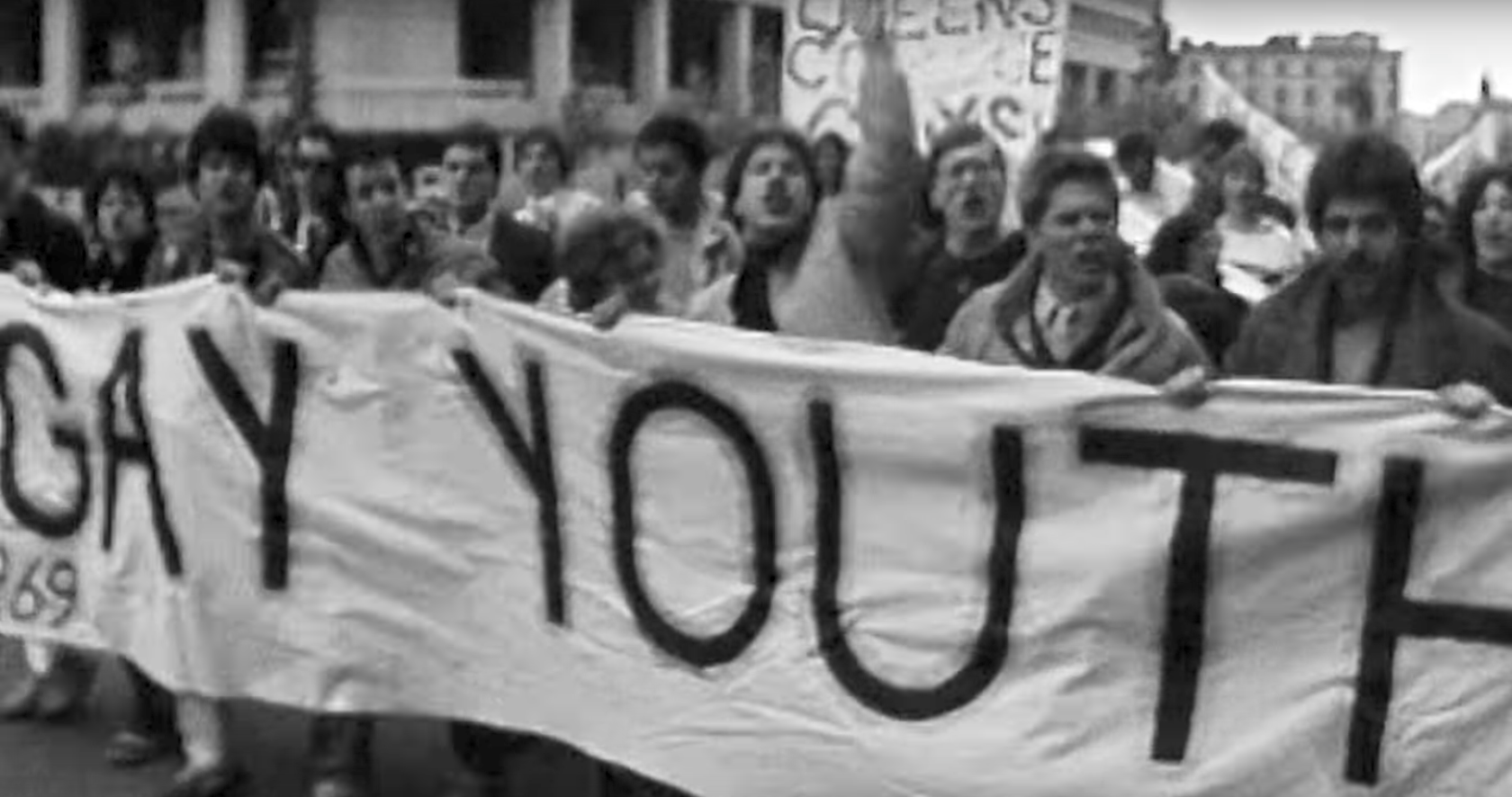

We have traditions. We have a style. We have a history—one that it seems queer youth are more and more interested in engaging with. Consider Connor Franta and Troye Sivan—young, gay YouTube stars who have used the platform and the popularity of their videos to bring attention to AIDS awareness, often by connecting their efforts to the U.S. AIDS epidemic in the1980s and early ‘90s. Their interest in this historical moment has visibly influenced these digital stars—evidenced in the fashions adapted by both Franta and Sivan. This is perhaps most visible in Sivan’s recent music video for his song “Heaven.”5 In the video, footage of gay rights activism dating back to at least the late ‘60s is interspersed with clips of Sivan, wearing an acid washed jean jacket with a popped collar. Several of these clips feature hospital scenes from the time of the AIDS epidemic. Both the historical scenes and the images of Sivan appear in black and white, which creates a clear connection between the past and present. This sense is only strengthened by Sivan’s attire that seems to place Sivan and the historical figures in the same moment in time.

What Sivan and Franta reveal is that despite the resistance of many queer theorists to acknowledge queer community, a certain type of kinship has nevertheless developed. While Sivan’s music video may be an artifact that develops this kinship, it also might be regarded more as proof of its having already been developed. Thus, in order to better understand how this kinship is developed, I look to David Levithan’s recent YA novel as an example.

In Over the Rainbow: Queer Children’s and Young Adult Literature, Michelle Ann Abate and Kenneth Kidd note that homosexuality “has become nearly a mainstream topic in YA literature.”6 Aiding this trend is Levithan, who is both a writer and a publisher of many contemporary YA titles with LGBTQ+ themes. His most recent work, Two Boys Kissing, illustrates multiple threads of a queer and intergenerational cultural inheritance. The narrative explores the lives of several gay teens, but what threads the narratives together is a chorus of deceased gay men—ghosts of those who died during the AIDS epidemic—who now oversee with joy and fear the younger generation of queer youth. Although this chorus of narrators never interacts with the characters in Levithan’s work, they frequently address the reader:

If you are a teenager now, it is unlikely that you knew us well. We are your shadow uncles, your angel godfathers, your mother’s or your grandmother’s best friend from college, the author of that book you found in the gay section of the library. […] We are the ghosts of the remaining older generation.7

Here, Levithan not only establishes a cultural history for queer youth, but further develops the sense of kinship in listing a number of familial relationships.

In asking his readers to identify with this queer past, he asks them to identify with an ongoing community: “We were once like you,” states the chorus, “A generation or two earlier, you might be here with us” (Levithan 2).

To see this exchange as a one-sided transaction would be a mistake, however. Levithan is not merely imparting queer wisdom to a younger generation; he invests in them. In this, he enacts the child-centric politics that Lee Edelman urges queer individuals to avoid.

In No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Edelman identifies the figure of the child as the central concern in the political discourses of the United States.8 Due to this “cult of the Child,” queerness is viewed as a threat that opposes reproductive futurity (Edelman 11, 19).

Edelman, like Halberstam, thus fears that efforts that keep the child as a centripetal figure will adopt a (hetero)normative model. In many ways, this is indeed the case as seen in Two Boys Kissing. The only boy whose narrative strays from a romantic (and normative) coupling follows him down a destructive path that eventually leads to the edge of a bridge. Yet, the novel also appeases queer theory in its attempts to proliferate categories of what it means to be gay:

Dreaming and loving and screwing. None of these are identities. Maybe when other people look at us, but not to ourselves. We are so much more complicated than that. (Levithan 6)

In this, we might see the intersection of a child-centrism that queer theory rejects and a celebration of queer theory that heteronormative society (at least according to Edelman) rejects.

My next post will continue exploring these ideas of representation and queer cultural inheritance.

- Heggestad, Jon. “Race, Racism, Privilege & the Weight of Mistakes | Young Adult Literature & Social Justice as Pedagogy.” Young Adult Literature & Social Justice as Pedagogy, 9 Sept. 2017, https://you.stonybrook.edu/yajustice/2017/09/09/race-racism-privilege-the-weight-of-mistakes/. ↩

- Thomas, Angie. The Hate U Give. Balzer Bray, 2017, p. 20. ↩

- Shusterman, Neal. Challenger Deep. HarperTeen, 2015, p. 229. ↩

- IPAK Centar. Jack Halberstam on Queer Failure, Silly Archives and the Wild. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iKDEil7m1j8. ↩

- Sivan, Troye. “HEAVEN ft. Betty Who.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 19 Jan 2017. Web. 16 Oct 2017. ↩

- Abate, Michelle Ann, and Kenneth B. Kidd. Over the Rainbow: Queer Children’s and Young Adult Literature. University of Michigan Press, 2011, p. 5. ↩

- Levithan, David. Two Boys Kissing. alfred a. knopf, 2013, p. 3. ↩

- Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Duke University Press, 2007, p. 11. ↩