Ellen Wittlinger’s Parrotfish centers on a month of big changes for high schooler Grady. He’s changed his look; he’s changed his name; and he’s told his parents that he’s not their son, not their daughter. And while he finds that these are “big changes” for everyone around him, he is unable to figure out why his transition has made such an impact in the lives of his friends, family, and classmates. Despite his growing conviction that gender is simply a construct, he is frequently frustrated by the limitations that these constructs enforce. From the very first pages of dialogue, Grady finds that gender is essentialized and prioritized, presented as “the first question”—as it literally does in the opening conversation about his new baby cousin. “Is it a boy or a girl?”1

Ellen Wittlinger’s Parrotfish centers on a month of big changes for high schooler Grady. He’s changed his look; he’s changed his name; and he’s told his parents that he’s not their son, not their daughter. And while he finds that these are “big changes” for everyone around him, he is unable to figure out why his transition has made such an impact in the lives of his friends, family, and classmates. Despite his growing conviction that gender is simply a construct, he is frequently frustrated by the limitations that these constructs enforce. From the very first pages of dialogue, Grady finds that gender is essentialized and prioritized, presented as “the first question”—as it literally does in the opening conversation about his new baby cousin. “Is it a boy or a girl?”1

While gender is often regarded as a category of the greatest importance, it is widely neglected as a subject in the school systems and in queer YA novels. Continuing my analysis of representation in queer YA novels, this blog post looks at gender variant and transgender characters. Similar to the current climate for racially and ethnically diverse characters in queer YA works, trans* characters are being made more and more visible, but there is still a great distance to be covered. Part of the problem seems to be that that the variety of gender identities are not merely compressed into a transgender category, but that this category is too often misrepresented as being more similar than it really is to those sexual identities that comprise the first three letters of the popular LGBT abbreviation. Bruce Parker and Jacqueline Bach observe that addressing the differences in these identities “requires a certain amount of unlearning.”2

As an example, Parker and Bach (along with others) cite that the “coming out” experiences of someone who identifies as gay compared to the experiences of someone who identifies as transgender are vastly different. For example, someone who is gay can come out gradually, to different people, to different extents, at different times, but a transgender individual has much fewer options: “Once they begin presenting differently as part of their transition process, they are immediately and abruptly out to those who knew them previously.”3

While the body of YA literature that describes the process of coming out for LGB individuals is fairly substantial, continuing to grow, titles that represent gender variant and/or transgender experiences are still extremely limited (Parker and Bach 98). But progress is being made.

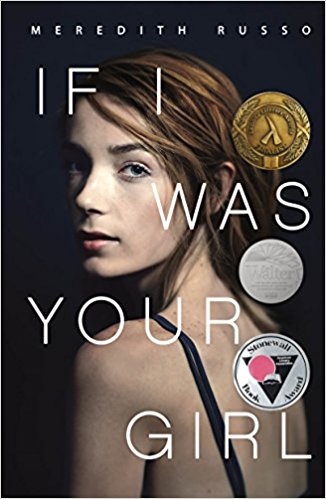

In addition to Parrotfish, mentioned above, Meredith Russo’s If I Was Your Girl also aims to make these experiences more. In this novel, Amanda tries to navigate the challenge of beginning her senior year at a new high school while struggling with the weight of her “secret”—i.e. that she is transgender, MTF. Although Russo crafts the novel with a wide and beautiful emotional range, the overall tone of the novel is somber.4 Amanda has had a tough life so far: feeling rejected by her dad, being bullied before her transition, and being attacked by a classmate’s parent after it. In many ways, her story continues to resonate with the same worries and fears that have become a commonplace in queer YA: “The message is hard to miss: LGBT characters are most useful if they’re dead or gone.”5 And while William P. Banks observes that many novels featuring sexual have begun to steer clear of these tropes, it seems that gender variant and transgender characters are unfortunately still working their way through them.

In addition to Parrotfish, mentioned above, Meredith Russo’s If I Was Your Girl also aims to make these experiences more. In this novel, Amanda tries to navigate the challenge of beginning her senior year at a new high school while struggling with the weight of her “secret”—i.e. that she is transgender, MTF. Although Russo crafts the novel with a wide and beautiful emotional range, the overall tone of the novel is somber.4 Amanda has had a tough life so far: feeling rejected by her dad, being bullied before her transition, and being attacked by a classmate’s parent after it. In many ways, her story continues to resonate with the same worries and fears that have become a commonplace in queer YA: “The message is hard to miss: LGBT characters are most useful if they’re dead or gone.”5 And while William P. Banks observes that many novels featuring sexual have begun to steer clear of these tropes, it seems that gender variant and transgender characters are unfortunately still working their way through them.

While the novel tends to employ these unfortunate, though well-worn tropes, the overall story that Russo weaves is anything but commonplace. In a video posted to her YouTube channel, the author stated that she wrote If I Was Your Girl because it was the story she had always wanted:

I never encountered a story written by someone like me. I also never encountered a story that spoke about people like me in a way that was positive and not tragic or hilarious or scary, and I think my life would have been completely different had I had a resource like that.6

In the same video, Russo states that although more stories are being written about transgender people, “none of those people are transgender” (Lee). While Russo cites this observation as one of the main reasons for setting out to write her novel, it also circles back to Wittlinger’s work.

Ellen Wittlinger identifies as a cisgender female, but her book—written from the perspective of an FTM teen—is still highly esteemed despite this difference, as seen in the video from a recent Trans Pride event. Here, Wittlinger’s message is much the same as Russo’s, despite their different standpoints: “My hope for [Parrotfish] is that it demonstrates to kids or to anyone who reads it that living your true life does not have to be terrifying or tragic.”7 And the attendees and MC at the event all seem enthusiastic toward Wittlinger’s representation of their experiences. This is perhaps most evident in the opening lines of the MC: “We also need to really support folks who are telling our stories and talking about us because we can’t be everywhere” (NewEnglandBlade).

As with the varied backgrounds of the YA authors who portrayed characters with disabilities in my earlier blog, here these authors’ standpoints are seen to be different, but valuable through their differences.

- Wittlinger, Ellen. Parrotfish. Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 3. ↩

- Parker, Bruce and Jacqueline Bach, “Gender Variant and Transgender Issues in a Professional Development Book Group.” The English Journal, vol. 98, no. 4, 2009, pp. 96–101, p. 91. ↩

- Cramer, Katherine Mason & Jill Adams, “The T* in LGBT*: Disrupting Gender Normative School Culture Through Young Adult Literature.” Teaching, Affirming, & Recognizing Trans* and Gender Creative Youth: A Queer Literacy Framework, edited by sj Miller, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 121-141, pp. 121-122. ↩

- At one point, Amanda wishes her earlier suicide attempt had been successful, but only a few chapters later, she rejoices that her body could ever feel so good (Russo 225). ↩

- Banks, William P. “Literacy, Sexuality, and the Value(s) of Queer Young Adult Literatures.” The English Journal, vo. 98, no. 4, 2009, pp. 33-36. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40503258. ↩

- Lee, Meredith, “If I Was Your Girl.” Online video clip. YouTube, 15 May 2016. Web. 28 Oct 2017. ↩

- NewEnglandBlade, “Ellen Wittlinger Reads from Parrotfish at New England Trans. Pride.” Online video clip. YouTube, 7 June 2008. Web. 28 Oct 2017. ↩

I was actually reading your article and found some really interesting information. The thing is quite clear that I just want to thank for it. Official Website