Overview

I am a marine ecologist with broad interests in trophic ecology, functional morphology, soft-bottom benthic ecology, and some evolutionary aspects of marine ecological processes. I also work in the field of macroevolution, with the most recent work being engaged in timing the radiation of the animal phyla by means of molecular divergence estimates. My students have worked a wide range of marine biological problems.

Current and Recent Research:

Climate change, latitude, and thermal ecology of fiddler crabs.

Fiddler crabs have planktotrophic larvae and in many cases these larvae are adapted to ride the tide, feed on the contintental shelf. As a result many species have very long coastal geographic distributions. For example, the eastern North American fiddler Leptuca pugilator is found from Cape Cod (latitude 41.75°N ) to the panhandle of Florida (latitude 30.0 °N). Our research and the work of others demonstrate that males must display and feed for days near burrow openings with severe thermal and hydric stress. But what are the consequences of living over such broad stretches of latitude? With climate change will populations at the low-latitude end of their range suffer severe enough thermal stress that low-latitude populations might become extinct? Is there strong selection along the latitudinal gradient, such that low-latitude populations are better adapted to warm stressful habitats and high-latitude populations are better adapted to lower temperatures? A team from Stony Brook (Jeff Levinton and students), University of Southern Mississippi (M. Zachary Darnell and students), and the University of Wisconsin (Warren Porter and Paul Matthewson) are combining field studies, thermal modeling, climate modeling, and laboratory investigations of function under thermal and hydric stress, funded by NSF.

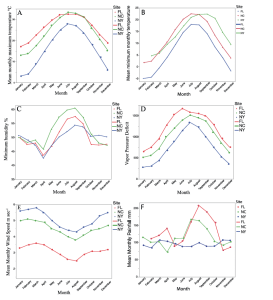

A central part of this study involves collection of weather data (temperature, humidity, wind speed) at the scale and microsite location of fiddler crabs. We have been installing weather stations that are exactly where the crabs live and we are collecting weather data just above and within the sediment.

Weather station at Flax Pond, New York – See Warren Porter explain the design and function of a weather station on the scale of a fiddler crab.

NEW RESULTS JUST PUBLISHED!

Superior Performance of a Trailing Edge Low-Latitude Population of an Intertidal Marine Invertebrate. Published in Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology

reference: Levinton, J., Arena, B., Pena, R., Darnell, M.Z. 2023. Superior performance of a trailing edge low-latitude population of an intertidal marine invertebrate. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 563, 151896, ISSN 0022-0981, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2023.151896. ![]()

Summary of Results:

The objective of this study was to compare ecologically relevant measures of performance over a broad range of latitudes of a species subjected to climate change. Do populations change in relative function over a wide range of latitude? Are populations at the low latitude trailing edge in danger of extinction in the onset of thermal stress? Coastal marine species with planktonic larvae can range over an enormous span of latitude and thermal environments. The fiddler crab Leptuca pugilator extends from high-latitude (41.75°N) winter-frozen Massachusetts tidal flats in the north to subtropical low latitude flats in Florida (24.55°N), where they may be active at the surface over most of the year. We characterized the air environment for males at three sites (New York – latitude 40.0°N, Beaufort, North Carolina – latitude 34.7°N, Panacea Florida, latitude 30.0 °N) over the geographic-thermal range, and found major differences in temperature, wind speed, humidity, and vapor pressure deficit. Florida L. pugilator males preferred warmer sand than North Carolina and New York crabs. Local adaptation to latitude-dependent thermal conditions might suggest tradeoffs in performance as a function of temperature. We examined measures of predator escape performance (running speed and righting speed) and overall condition reflecting endurance rivalry success (endurance on a treadmill and major claw closing force) over a wide range of test temperatures. Predator escape rates increase steadily with increasing temperature, but endurance rivalry measures show an intermediate temperature peak of performance. We tested the hypothesis of tradeoffs, with expected local superiority of performance according to regional thermal differences. But instead, the trailing edge Florida males were superior to the higher latitude populations, over a broad range of temperature, but especially at higher temperatures, for all four types of performance measures. The trailing edge population of L. pugilator, in thermal terms, is therefore likely not vulnerable to near future further effects of warming in terms of performance measures related to male reproductive and feeding activities and escape from predators. Fiddler crabs appear to display niche conservatism for stronger performance at tropical temperatures. Such a natural tropical superiority in performance might have to be accommodated in future conceptions of response of marine species to climate change with broad latitudinal distributions in the tropics.

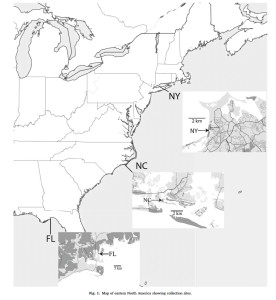

We collected Leptuca pugilator from three sites spread over the thermal-latitudinal range.

Collecting Sites: Stony Brook NY, Beaufort NC, Panacea FL

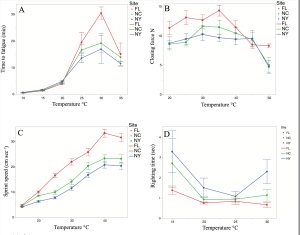

In figures below, red = Florida, green = North Carolina, blue = New York.

We were able to characterize the thermal-hydric environment at the three sites, using Niche-Mapper.com (thanks to our colleagues Paul Matthewson and Warren Porter from the University of Wisconsin.

As might be expected, the Florida locality was warmest, with a broad part of the year suitable for activity. Our observations and those of others show that males can be active feeding at the surface in December in Florida, but such activity ceases in NY by early October. Reproductive activity in NY ceases in late August. One interesting surprise is the high humidity of the intermediate locality in North Carolina.

The performance data, is based on four traits: Sprint speed and righting speed are traits that we believe reflect escape potential from predators such as birds and small mammals. Major claw closing force and endurance on a treadmill are traits that may reflect endurance rivalry fitness for males that are displaying, feeding and involved in combat near breeding burrows. The figure below shows that the Florida individuals (red) have longer enduraance and higher major claw closing force over a wide range of temperatures. The same superiority holds for Florida individuals for sprint speed. All results are highly significant (see details of analysis in paper). Righting speed also is greater for FL males, but the the differences from males in other localities is smaller. Overall, our results support the conclusion that the population at the trailing edge appears to be superior in performance at higher temperatures, and warming from climate change is unlikely to be a cause of population extinction in the near future. It may be that a basic adaptation to tropical conditions confers a superiority to lower latitude individuals. We also found that FL individuals preferred higher sediment temperatures than NC and NY crabs, when acclimated and placed in a thermal gradient.

Thermal performance: Upper left: time to fatigue on a treadmill; Upper right: closing force of the major claw; Lower Left: sprint speed; Lower right: righting time. FL = red, NC = green, NY = blue.

Behavior, biomechanics, evolution of fiddler crabs.

The overall objective of this study is to link the origin of an evolutionary innovation, namely the giant major claw of fiddler crabs, to reproductive function, behavioral evolution and biogeography of a widespread group. The fiddlers are pantropical and the major claw is nearly half the weight of the animal. It is used by males in threat display and combat. We are investigating the following questions: (1) Does the claw function as mainly display, or does its biomechanical features reflect a fully functioning closing structure? (2) Is sexual selection a cause of variability in this structure, much as the process works to increase variability of other structures and colors controlled by sexual selection? (3) Did behavioral complexity increase in this group, or did other factors allow the evolution of complex reproductive behavior? (3) Did this group arise in the IndoPacific as previously believed? Our work combines field studies of behavior, morphometrics, molecular phylogenetic tools, and biomechanics to answer these questions.

Recent research has focused on the functional morphology of the sexually selected major claw, which is nearly half the mass of a male fiddler crab. The claw is used in display and combat. Our previous work demonstrated that the major claw is fully functional and that variation of closing force with body size can be predicted successfully from simple measurements of claw dimensions, related to a simple lever system. However, there is a paradoxical result: As body size increases the closing force of the smaller feeding claw increases with the square of any linear measurement, as expected from a proportional increase to muscle cross-sectional area. But the closing force of the major claw proportionally decreases with increasing body size, mainly because the mechanical advantage decreases. Thus a fighting male is weaker than it would otherwise be if it maintained the same claw mechanical proportions of smaller crabs. I have been working on explaining this paradox – why be weaker than you were going to be? Is the claw used more for display? Is some other function being served? Thus far, we have concluded that there is a tradeoff between strength and closing speed and have tested this successfully. Thus larger crabs may require speed of clasping more than strength. This fits in with observations of combat and the usual lack of severe damage that one male might inflict upon another. I believe that this general result applies to many beetles bearing pincers as well. The race is to the swift, not necessarily to the strong.

We are also working on measuring the costs encumbered by having such a large structure as the major claw. In males of Uca pugilator and other species, this size is so large that the walking limbs beneath the cheliped are more robust than the legs beneath the much smaller feeding claw. Do males pay a price by carrying this large structure? Do they escape more poorly from predators? Do they have high metabolic loads, since this claw as a high proportion of the total striated muscle of the whole crab? We have been investigating the cost by measurements of metabolic rate, subjecting crabs to stress on a treadmill, and measuring running speeds of males in the field, as compared with males not bearing the large major claw.

A final functional emphasis is on the thermal component of fiddler crab performance. Fiddler crabs are an excellent model for the study of thermal stress on a mobile species in the intertidal zone and climate change may have strong impacts on behavior, mating strategies and survival. We have found that male size is related to vulnerability to thermal stress and this may contribute to larger-male mating success. We are investigating tradeoffs between sexual display and physiological stress. This study is embedded in a current National Science Foundation research grant devoted to latitudinal thermal adaptations of Leptuca pugilator, in collaboration with Zachary Darnell (University of Southern Mississippi) and Warren Porter (University of Wisconsin).

A recent study examined heartbeat in fiddler crabs in air and water. In water heartbeat increased from 20-40C and then declined to zero at 50C. But in air, heartbeat reached a peak at ca 35C but then had a very shallow decline, suggesting that increased temperature had less effect on heart output. This may be due to the fact that there is more aerobic scope in air at higher temperature than in water. See this publication:

Levinton, J., N. Volkenborn, S. Gurr, K. Correal, S. Villacres, R. Seabra, F. P. Lima, 2020. Temperature-related heart rate in water and air and a comparison to other temperature-related measures of performance in the fiddler crab Leptuca pugilator (Bosc 18020. Journal of Thermal Biology 88 (2020) 10252

Here are other publications:

Mathewson, P.D., Darnell, M.S., Lane, Z.M., Yeghissian, T.G., Levinton, J.S., Porter, W.2023.Incorporating species-specific morphology improves model predictions of thermal and hydric stress in the sand fiddler crab, Leptuca pugilator. J. Therm. Biol. 115: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2023.103613 .

Levinton, J.S., Weissburg, M. 2021. Size of a sexually selected structure: One way, over deep time and global space. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 2021; https://doi.org/10.1093/jcbiol/ruab066.

Levinton, J.S. 2016. Bilateral linkage of monomorphic and dimorphic limb sizes in fiddler crabs. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 119:370-380.

Levinton, J., Lord, S., Higeshide. 2015. Are crabs stressed for water on a hot sand flat? Water loss and field water state of two species of intertidal fiddler crabs. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 469: 57-62.

Allen, B.J., and J.S. Levinton. 2014. Sexual selection and the physiological consequences of habitat choice by a fiddler crab. Oecologia 176:25-34. DOI 10.1007/s00442-014-3002-y

Levinton, J.S., Mackie. 2013. Latitudinal diversity relationships of fiddler crabs: biogeographic differences united by temperature. Global Ecology and Biogeography.DOI: 10.1111/geb.12064 ![]()

Munguia, P., Levinton, J.S., Silbiger, N.J. 2013. Latitudinal differences in thermoregulatory color change in Uca pugilator. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 440: 8-14. ![]()

Allen, B.J., Rodgers, B., Y. Tuan, Levinton, J. 2012. Size-dependent temperature and desiccation constraints on performance capacity: implications for sexual selection in a fiddler crab. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 438:93-99. ![]()

Allen, B., Levinton, J.S. 2007. Costs of bearing an ornamental weapon in a fiddler crab. Functional Ecology 21:154-161. ![]()

Levinton, J.S., B. Allen. 2005. The paradox of the weakening combatant. tradeoff between closing force and clasping speed in a sexually selected combat structure. Functional Ecology 19: 159-165 ![]()

Allen, B., Levinton, J.S. in preparation. Three measures of cost of a sexually selected combat structure.

Levinton, J.S. in preparation. Positive correlations rather than a tradeoff between mass of a sexually selected structure and a developmentally related feeding structure. in preparation

Levinton, J.S., Sturmbauer, C., J. Christy. 1996. Molecular data and biogeography: resolution of the evolutionary history of a pantropical group of invertebrates. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 203:117-131. ![]()

Sturmbauer, C., J. Christy, J. S. Levinton. 1996. Molecular phylogeny analysis of fiddler crabs: Test of the hypothesis of increasing behavioral complexity in evolution Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 93:10855-10857. ![]()

Levinton, J.S., Judge, M., Kurdziel, J. 1995. Functional differences between the major and minor claws of fiddler crabs (Uca, family Ocypodidae, Order Decapoda, Subphylum Crustacea): A result of selection or developmental constraint. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 193: 147-160. ![]()

Levinton, J.S., and M. L. Judge. 1993. The relationship of closing force to body size for the major claw of Uca pugnax (Decapoda: Ocypodidae). Functional Ecology, 7: 339-345. ![]()

Physiological Performance, and Potential for Restoration of the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginia.

The overall objective of our work is to produce a physiological map of growth, survival, susceptibility to disease, and recruitment of oysters in the New York region. Oysters were once very abundant but are now rare, owing to overexploitation and pollution. We are focusing on areas thought to be useful for restoration to take advantage of the oysters useful ecosystem services, including enhancement of fish and invertebrate biodiversity and local reduction of phytoplankton density. We have chosen nine sites with strongly varying water quality, salinity to develop a map of performance. This will be combined with the development of a strategy for deploying artificial oyster reefs that produce a sustainable metapopulation of oysters in a restricted region, such as Jamaica Bay, New York and Haverstraw Bay, in the Lower Hudson estuary. This work is being done in collaboration with Michael Doall, Director, Functional Ecology Research and Teaching Laboratory, Stony Brook University.

Publications and Reports

Sebastiano, D., Levinton, J., Doall, M., Kamath, S. 2015. Using a shellfish harvest strategy to extract high nitrogen inputs in coastal bays: Practical and economic implications. Journal of Shellfish Research, 34: 573-583.

Levinton, J., Doall, M., Allam, B. 2013. Growth and mortality patterns of the eastern oyster Crassostrea virgin

ca in impacted waters in coastal waters in New York, USA. Journal of Shellfish Research. 32: 417-427.

Starke, A., Levinton, J., Doall, M. 2011. Restoration potential of Crassostrea virginica to the Hudson River, USA: A Spatio-temporal modeling approach. J. Shellfish Res., 30(3):671-684.![]()

Hear Jeff Levinton and Mark Kurlansky on the Brian Lehrer Show, WNYC

Hear Jeff Levinton and Ken Paynter on the Leonard Lopate Show, WNYC, March 25, 2010

Evolution of resistance to metals and restoration ecology.

We have discovered rapid evolution of resistance to cadmium in an aquatic oligochaete and have shown that the trait is strongly heritable and probably controlled by one gene. The evolution of resistance in this system was under strong selection and likely occurred in less than five generations. In the lab we were able to accomplish 2/3 of the resistance observed in the field over three generations of selection. We are now attempting to understand the molecular basis of the resistance and also are studying the reversion of resistance as the cove is being cleaned up in a Superfund project. We are also actively investigating the impacts of a major Superfund cleanup that occurred at Foundry Cove, Hudson River, in 1994-1995. We observed a reversion of the resistance to background levels in onlhy nine years following the cleanup (Levinton et al. 2003). We also observed strong reorganization in the benthic community following the cleanup (Kelaher et al. 2003). We are now working further on the question of cost of evolution of the resistance trait. As a side project we analyzed mercury concentrations, using a large data base of fish analyses in the Hudson River USA. We found a 30 year decline in concentrations by a factor of 2-3, but a persistent increase of Hg concentrations toward the north. We speculated that the source might be the Adirondack watershed.

Klerks, P., Xie, L., Levinton, J.S. 2011. Quantitative genetics approaches to study evolutionary processes in ecotoxicology; a perspective from research on the evolution of resistance. Ecotoxicology 20: 513-523. ![]()

Mackie, J., Levinton, J.S., Przselawski, R., DeLambert, D., Wallace, W. 2010. Loss of Evolutionary Resistance by the oligochaete Limnodrilus hoffmeisteri to a Toxic Substance—Cost or Gene Flow? Evolution, 64:152-165. ![]()

Levinton, J.S., S.T. Pochron. 2008. Temporal and geographic trends in mercury concentrations in muscle tissue in five species of Hudson River, USA, fish. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 27: 1691-1697. ![]()

Mackie, J., Natali, S., Levinton, J., Sanudo-Wilhelmy, S. 2007. Declining metal levels at Foundry Cove (Hudson, New York): response to localized dredging of contaminated sediments. Environmental Pollution, 149: 141-148. ![]()

Levinton, J.S., S.T. Pochron, M.W. Kane. 2006. Superfund dredging restoration results in widespread regional reduction of cadmium in blue crabs. Environmental Science & Technology 40: 7597-7601. ![]()

Levinton, J. S., Suatoni, L., Wallace, W. P., Junkins, R., Kelaher, B.P., Allen, B.J. 2003. Rapid Loss of genetically-based resistance to metals, following the cleanup of a Superfund site. PNAS 100: 9889-9891. ![]() Corrected figure Press Release Photos

Corrected figure Press Release Photos

Kelaher, B. P., Levinton, J. S., Oomen, J. Allen, B. J., Wong, W.H. 2003. Changes in benthic communities following the clean up of a severely metals polluted cove in the Hudson River Estuary: environmental restoration or ecological disturbance? Estuaries, 26: 1505-1516. ![]()

Levinton, J.S., P. Klerks, D.E. Martinez, C. Montero, C. Sturmbauer, L. Suatoni,W. Wallace. 1999. Running the Gauntlet: Pollution, Evolution and Reclamation of an Estuarine Bay and its Significance in Understanding the Population Biology of Toxicology and Food Web Transfer. IN M. Whitfield, ed., Aquatic Life Cycles Strategies. Plymouth U.K., The Marine Biological Association. ![]()

Wallace, W.G., Lopez, G.R., Levinton, J.S. 1998. Cadmium resistance in an oligochaete and its effect on cadmium trophic transfer to an ominvorous shrimp. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 172: 225-237. ![]()

Martinez, D.E., and J.S. Levinton 1996. Adaptation to cadmium in the aquatic oligochaete Limnodrilus hoffmeisteri: Evidence for control by one gene. Evolution, 50: 1339-1343. ![]()

Klerks, P., Levinton, J. 1992. Evolution of resistance and changes in community composition in metal-polluted environments: A case study on Foundry Cove.In Dallinger, R., Rainbow, P. (eds.), Ecotoxicology of Metals in Invertebrates. Lewis Publ., Chelsea, pp. 223-241.

Klerks, P.L., and J.S. Levinton. 1989. Rapid evolution of resistance to extreme metal pollution in a benthic oligochaete. Biol. Bull. 176:135-141. ![]()

Biodynamics of Particle Selection by Suspension Feeders.

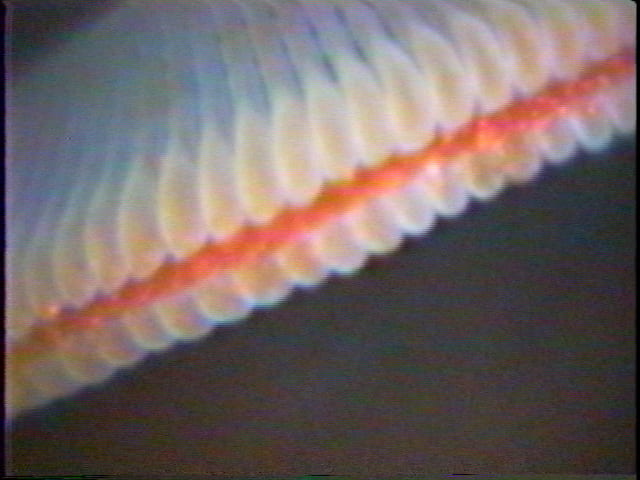

With Evan Ward and Sandy Shumway, I am working on the mechanisms of bivalve feeding, using flow cytometry, surgical telescopes, and videotaping to study the ability of bivalves to sort particles and adjust feeding rates in response to variations in particle concentration and complex particle arrays. The questions involve whether given parts of the feeding apparatus comprise a rate-limiting step to feeding, and whether bivalves can use selectivity to sort among complex arrays of non-living and living particles in environments such as estuaries. We hope to do a comparative study among different bivalve groups but are concentrating on a few oyster, scallop, mussel, arcid spp. as well as Zebra mussels.

Recent results have combined video endoscopy with flow cytometry to sample in different parts of the pallial cavity. We have discovered extensive particle selectivity on the gills of oysters and zebra mussels. In oysters, rapid shunting allows particles of poor nutritive quality to be rejected and nutritious particles to be diverted towards the mouth. A video of these results can be found here. In the case of zebra mussels, the selectivity has been related to a change in phytoplankton species dominance, following the invasion by zebra mussels of the Hudson River. We have also recently shown that oysters and mussels can detect the presence of polyphenolics in kelp detrital particles. Evan Ward’s summary of particle transport in the mussel Mytilus edulis can be found here.

Our most recent work has focused on the possibility that bivalves may be able to capture and consume much larger and more active food particles than previously appreciated. A number of studies have suggested that bivalves can feed upon zooplankton particularly smaller forms such as ciliates. We have demonstrated that zebra mussels and two species of marine mussels can clear rotifers from the water column and can assimilate carbon at levels high enough to be meaningful to bivalve nutrition. We have suggested that there is a benthic-zooplankton loop that might strongly implicate dense populations of benthic suspension feeders in control of near shore water column communities. Instead of competing with zooplankton for microphytoplanktonic food, they may be top-down predators on the whole system.

The capture of zooplankton by bivalves has been demonstrated in a number of field studies, but the most intriguing evidence comes from invasions of the Asiatic clam and the Zebra mussel, both of which were followed in some water bodies by precipitous declines of micro and mesozooplankton. In the lab we demonstrated that zebra mussels can capture, ingest, and assimilate rotifers of lengths as large as ca. 300 micrometers. Using 14C labeled rotifers, we found high efficiencies (Wong et alo. 2003a, b). We also found a positive synergistic interaction resulting in high shell growth ot the mussel Mytilus edulis, when fed combined rotifers and phytoplankton, as opposed to either alone (Wong and Levinton 2004). Our most recent work in collaboration with Jeannette Yen, Brock Woodson and Marc Weissberg of Georgia Tech demonstrates very different capture success of copepods by mussels in still and moving water. These results will be presented at ASLO in 2005. Some preliminary movies and images can be viewed here.

Wong, W.H., 2006. The trophic linkage between zooplankton and benthic suspension feeders: Evidence from fecal pellets. Marine Biology 148: 799-805.

Wong, W. H., Levinton, J.S. 2005. Consumption rates of two rotifer species by zebra mussels Dreissena polymorpha. Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology. 38: 149-157.

Wong, W. H., Levinton, J. S. 2004. Culture of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis (Linnaeus, 1758) fed both phytoplankton and zooplankton: A microcosm experiment.Aquaculture Research, 35:965-969.

Wong, W.H., Levinton, J. S., Twining, B. S., Fisher, N. S. Kelaher, B. P., Alt, A. K. 2003. Assimilation of carbon from a rotifer by the mussels, Mytilus edulis and Perna viridis: A potential food web link between zooplankton and benthic suspension feeders. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 253: 175-182.

Wong, W.H., Levinton, Twining, B.S., Fisher, N.S. 2003.Assimilation of micro- and mesozooplankton by zebra mussels: a demonstration of the food web link between zooplankton and benthic suspension feeders. Limnol Oceanogr. 48: 308-312. ![]()

Baker, S. M., Levinton, J. S. 2003. Selective feeding by three native North American freshwater mussels implies food competition with zebra mussels. Hydrobiologia 505: 97-105. ![]()

Ward, J. E., J. S. Levinton, S. E. Shumway. 2003. Influence of diet on pre-ingestive particle processing in bivalves I: Transport velocities on the ctenidium. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 293: 129-149. ![]()

Levinton, J. S., J. E. Ward, S. E. Shumway. 2002. Feeding responses of the bivalves Crassostrea gigas and Mytilus trossulus to chemical compositon of fresh and aged kelp detritus. Mar. Biol. 141: 367-376. ![]()

Levinton, J.S., J.E. Ward, S.E. Shumway, S. M. Baker. 2001. Feeding Processes of Bivalves: Connecting the Gut to the Ecosystem. Pp. 385-400. In Organism-sediment Interactions, ed. J. Y. Aller, S. A. Woodin, R. Aller, Belle W. Baruch Library in Marine Science no. 21. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC 29208 ![]()

Baker, S., J.S. Levinton, J.E. Ward. 2000. Particle transport in the zebra mussel, Dreissena polymorpha (Pallas). Biol. Bull. 199:116-125. ![]()

Baker, S. M., J.S. Levinton, J. P. Kurdziel, S.E. Shumway. 1998. Selective feeding and biodeposition by zebra mussels and their relation to changes in phytoplankton composition and seston load. J. Shellf. Res. 17: 1207-1213. ![]()

Ward, J.E., J.S. Levinton, S.E. Shumway, T. Cucci. 1998. Particle sorting in bivalves” in vivo determination of the pallial organs of selection. Mar. Biol. 131: 283-292. ![]()

Ward, J.E., J.S. Levinton, S.E. Shumway, T. Cucci. 1997. Site of particle selection in a bivalve mollusc. Nature 390: 131-132. ![]()

Levinton, J.S., J. E. Ward, R. Thompson. 1996. Biodynamics of particle processing in bivalve molluscs: models, data, and future directions. Invertebrate Biology 115: 232-242.

Levinton, J.S. 1991. Variable feeding behavior in three species of Macoma (Bivalvia: Tellinacea) as a response to water flow and sediment transport. Marine Biology 110:375-383.

Testing the Cambrian Explosion Hypothesis.

With Gregory Wray, and Leo Shapiro, I have used molecular distance – fossil divergence data to estimate the time of divergence of the animal phyla. Our results, based on analyses of large number of taxa for 7 genes, suggests that the animal phyla (protostome-deuterostome split) diverged far before the Cambrian. We are now using simulations to test whether one can recover a “tree of life” when divergences occur at varying times before the present and over different periods of time. Initial results suggest that the extreme version of the Early Cambrian explosion could never be detected. Our analyses of real molecular sequences, however, do allow us to define the order of appearance of major groups. This suggests that the radiation of animals took place over a more protracted period.

Levinton, J.S., 2008. The Cambrian explosion: How do we use the evidence? BioScience 58: 855-864. ![]()

Recent Interview about the Cambrian Explosion by AIBS

Levinton, J.S., L. Dubb, G. A. Wray. 2004. Simulations of evolutionary radiations and their application to understanding the probability of a Cambrian explosion. J. Paleontol. 78: 31-38. ![]()

Levinton, J. S. 2001. Genetics, Paleontology and Macroevolution. 2nd ed. New York, Cambridge Univ. Press.

Wray, G., J.S. Levinton, L. Shapiro. 1996. Molecular evidence for deep Precambrian divergences among metazoan phyla. Science 274: 568-573. ![]()

Levinton, J.S. 1992. The big bang of animal evolution. Scientific American, November issue, pp. 84-91.

Trophic limitation and population dynamics of deposit feeding invertebrates.

For many years I have been working on food limitation of deposit feeders. The overall objective is to study functional aspected of feeding and to connect these studies to population regulation of field populations and communities. This work began with models and studies of food limitation of deposit feeders that fed on a renewable resource, namely sediment associated microbes and algae. In more recent years I have focused on the dynamics of particulate organic matter supply and population responses.

Recently we have been working on an asexual oligochaete that undergoes a boom and bust cycle every summer, that appears to be related to the appearance and decline of a food base. We have shown (Cheng et al. 1993) that organic matter steadily declines in nutritional quality thorughout the spring and populations finally decline in the early summer. this is a general theme in intertidal mud flats dominated by surface and near surface-feeding deposit feeding annelids. We have recently discovered a behavioral-reproductive switch that appears when food is limited. This is a form that fails to bud and becomes a large active swimmer and is apparently a migratory individual. We are now doing spatial modeling to understand the implications of such an emigratory form.

We have completed recently a field assay of emigration, using a device to estimate the proportion of Paranais litoralis that depart from the sediment. As found in the past, sediment-dwelling P. litoralis showed a strong peak in the spring, followed by a precipitous decline. The relative number of “swimmers” increased at or after the seasonal peak abundance of worms as predicted from previous laboratory discoveries. They are probably the first to demonstrate an ecological context, in terms of resources, for swimming from the sediment by soft-bottom benthos. We also have quantified for the first time, simultaneously, emigration and immigration (Junkins et al. 2006).

Our most recent efforts have also been directed toward extending laboratory experiments on food inputs to field situations. We completed a spatial sampling program that demonstrates that seasonal boom-bust cycles of annelids in Long Island salt marsh mud flats are spatially variable in time course, leading to strong spatial-temporal variation of cycles of surface feeding deposit feeders, such as the oligochaete Paranais litoralis and the polychaete Streblospio benedicti. Field manipulation experiments demonstrate that the system of surface feeders is food limited and that the mobile snail Ilyanassa obsoleta exerts negative effects on populations of deposit feeding annelids. Field experiments demonstrate that I. obsoleta populations move to local inputs of particulate organic detritus inputs, which in turn, tends to reduce population growth of surface deposit feeders. Thus, overall, there appears to be competition between the bottom-up input of food, which is spatially localized, and the top-down effect of the mobile consumer, Ilyanassa obsoleta.

Junkins, R., Kelaher, B., Levinton, J. S. 2006. Contributions of adult oligochaete emigration and immigration in a dynamic soft-sediment community. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 330: 208-220. ![]()

Levinton, J. S., Kelaher, B. P. 2004. Opposing organizing forces of deposit-feeding marine communities. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 300, 65-82. ![]()

Kelaher, B. P., Levinton, J.S. 2003. Variation in detrital-enrichment causes changes in spatio-temporal development of soft-sediment assemblages. Marine Ecology Progress Series. kel![]() herlevintonmeps

herlevintonmeps

Kelaher, B. P., Levinton, J. S., Hoch, J. M. 2003. Foraging by the mud snail, Ilyanassa obsoleta (Say), modulates spatial variation in benthic community structure. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 292:139-157. ![]()

Nilsson, P., J. S. Levinton, J. Kurdziel. 2000. Migration of a marine oligochaete: induction of dispersal and microhabitat choice. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 207: 89-96. ![]()

Nilsson, P., J.Kurdziel, J.S. Levinton. 1998. Heterogeneous population growth, parental effects and genotype- environment interactions of a marine oligochaete. Marine Biology, 130: 181-191. ![]()

Levinton, J.S. 1995. Bioturbators as ecosystem engineers: Population dynamics and material fluxes, pp. 29-36 IN C.G. Jones and J. H. Lawton, eds., Linking Species and Ecosystems, New York, Chapman and Hall ![]()

Cheng,I-J., J.S. Levinton, M. McCartney, D. Martinez, and M.J. Weissburg. 1993. A bioassay approach to seasonal variation in the nutritional value of sediment. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 94: 275-285.

Levinton, J.S., McCartney, M.M. 1991. The use of photosynthetic pigments as tracers of sources and fates of macrophyte organic matter in a sand flat. Marine Ecology – Progress Series, 78:87-96.

![]()

Thesis topics of most recent PhD students who have gotten their degrees in areas discussed above.

1. Daniel Martinez – study of senescence and life history in invertebrates, in relation to presence and absence of sexual reproduction. Now Prof., Pomona College

2. Mike McCartney – study of male reproductive effort and its importance in varying hermaphroditic strategies in a bryozoan. Now Resarch Professor at Univ. Minnesota

3. Sean Craig – study of the importance of fusion in the biology of bryozoans. Now Professor, Cal. State at Humboldt

4. Marc Weissburg – study of foraging biology and optimal foraging in fiddler crabs. Now Prof. at Georgia Tech University

5. Josepha Kurdziel – study of the factors that select for male dimorphism in the amphipod Jassa marmorata, now Asst. Prof. at U. of Michigan

6. Michael Rosenberg – study using geomorphometrics and other approaches to understand morphological variation, functional morphology and phylogeny of fiddler crabs. now Professor at Arizona State.

7. Bengt Allen – reproductive and physiological performance of the fiddler crab Uca pugilator, relating performace to thermal stress and food availability. now Assoc. Professor at California State University at Long Beach.

8. J. Matt Hoch – reproductive effort, fertilization success and morphological plasticity in acorn barnacles. now Associate Professor at Nova Southeastern University.

9. Chris Noto (coadvisor with Dr. Catherine Forster) – taphonomy and its influence on our understanding of dinosaur preservation and diversity patterns, now assistant professor at University of Wisconsin, Parkside.

10. Patrick Lyons – The evolution of mutualism between alpheid shrimp and gobiid fishes, now Assistant Professor, Valley College, California.

11. Abigail Cahill (BS Colgate University), Climate change and larval ecology and population genetics of slipper shells. now Assistant Professor Albion College, Michigan