TRIENNIAL REPORT 2018-2019

Making Scientific Research Count at Stony Brook University!

News and Research Highlights

Research is fundamental to the SoMAS mission. The research conducted at SoMAS seeks to understand the way the marine, atmospheric and terrestrial environments function, as well as the effects and impacts of human interactions with these systems. These problems all require knowledge from multiple disciplines and the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences encourages interdisciplinary research. Many of our faculty pursue research in collaboration with scientists at other University departments as well as with scientists from academic institutions around the country and the globe. Unlike many academic institutions, we do not have traditional departments at SoMAS. What we do have is a large number of faculty and students who work together to better understand our planet.

All SoMAS faculty are expected to maintain an on-going research program that meets the highest standards of scientific inquiry and to regularly publish the results of their work in refereed scientific journals and other outlets. Research at SoMAS is generally carried out by a team headed by a faculty member that includes his/her graduate students, often aided by one or more undergraduate students. Some of the larger projects employ full- or part-time research technicians and/or postdoctoral associates.

Research at SoMAS is externally-funded. Our faculty have a well-deserved reputation for success in securing grants and contracts from a wide variety of sponsors at the federal, state, and local levels. Among the most frequent and important sponsors of research at SoMAS are several U.S. federal agencies: National Science Foundation (NSF); National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA); National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); Department of Energy (DOE); Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Office of Naval Research (ONR).

The following pages contain brief synopses of research projects underway at SoMAS that are representative of the breadth and diversity of research at the School. More complete information on SoMAS research is available on the “Research” pages of our web site, as well as under the profiles of individual faculty members

Wayne Penello ’79 Talks Risk Management

From Wayne Penello ’79 Talks Risk Management on Stony Brook Matters, by Kristen Brennan, on November 18, 2020.

Wayne Penello ’79 is not afraid to take risks. In fact, he’s built a career out of it.

As president and founder of Risked Revenue Energy Associates, Penello helps companies understand the importance of risk management. Now, he’s sharing his 40 years of experience in Risk is an Asset — a book he penned alongside his colleague Andrew Furman that has been published by Forbes Books.

But Penello wasn’t always in risk management. With a master’s degree in Marine Sciences from Stony Brook University, he began his career as a research scientist. Somewhat unexpectedly, Penello told us, it’s his research training and his experience at Stony Brook — that led to his success in business. Penello even dedicated his book to his professors at Stony Brook, acknowledging their role in his career.

Tell us more about your journey from Stony Brook University to your role as president of Risked Revenue Energy Associates and now author?

As a businessperson specializing in commodity price risk management, I’ve had the privilege of working on a vast range of complex problems. The education I received at SBU helped me develop a foundation of skills that eventually led to my understanding of statistics and chaotic systems.

My late advisor, Bud Brinkhuis, was a researcher and professor who made every effort to broaden my analytical and communication skills. His influence and support gave me the confidence to approach and obtain the training I needed from several other excellent scientists, both on campus and elsewhere. As a graduate student, I conducted experiments and studied at Cornell’s Veterinary College, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Brookhaven National Laboratory and Stony Brook’s medical school. I also was part of a research team of marine scientists that took samples across the Caribbean Sea. Bud was my advocate through everything. The breadth of experiences offered by Bud and the other scientists and the access each of them afforded to me played an important role in opening my eyes to my own potential and accelerating my growth.

It sounds like your experience as a student had a profound impact on your career. Can you tell us more about that?

While I was a student, something magical happened. I took a statistics course that was then called Biometry, which introduced me to Analysis of Variance. At the time, it was a relatively new statistical tool and had only just become popular because computing costs had come way down. This course was my epiphany. I loved the course.

Back then, most students would sit for hours at the Computer Center punching cards that would program the computer to solve their homework problems. My challenge was that the Marine Science Research Center was on the South Campus, and the Computer Center was on the Main Campus. The bus ride between the two could easily take 45 minutes each way. I needed a more efficient way to get my work done.

Using my Texas Instrument TI-100, a hand-held calculator with 99 programmable steps, I broke the programs for each statistical test into a series of subroutines, each small enough to fit on the calculator. This allowed me to solve these problems in my South Campus office, saving me a lot of time. More importantly, by delving deeply into the math for analysis of variances, I developed an appreciation for the logic behind the tool. I was so excited about my new knowledge that even before the course was over, I started looking for ways to apply my new skills everywhere. I was fortunate to publish research papers with several scientists and professors who used these tools to further their research. These collaborations gave me the confidence to look beyond the opportunities at Marine Sciences.

What inspired you to take the leap and write Risk is an Asset?

I want businesses subject to commodity price risk to become resilient by maintaining appropriate levels of protection. When a company fails, it affects many people. Investors lose money, but employees lose their jobs and sometimes their retirement savings. My hope is that if managers have a better understanding of their risk, they will appreciate the benefits of process risk management and adopt it. Rather than focusing on math, my book explains its application and the utility of risking budgetary performance estimates. I wrote the book in a way that makes it approachable for students, in the hope that they will read and learn from it. These students will be the next generation of business leaders; hopefully, this book will help them prepare for many challenges.

With your degree in marine sciences, you began your career as a research scientist. How does this factor into the work you do today?

One of the great dangers in today’s world is that disinformation is continually being circulated and re-circulated. One publisher will print a knowingly false statement, only to retract it the next day. Unfortunately, before that happens, other news publishers will regurgitate that information as if it were true. This creates a long trail of referenced information that is wrong. Today, we must all challenge and check facts. My training as a research scientist helped me develop into a critical thinker and prepared me for today’s challenge of sifting through multiple and independent sources of information to find the data I can trust.

What advice would you give to students looking to follow in your footsteps?

If you’d like to make a lot of money, solve BIG problems. The bigger the problems you solve, the more likely you are to get paid well. But you also need to be good at solving these problems, so pick something that interests you. I have been fortunate to have loved going to work every day of my life. That allowed me to live a life filled with passion. If you can, make your avocation your vocation. Then you will love your work and have a good chance to become great at it. If there is someone out there who is doing the things you are interested in and good at it, go work for them. Surround yourself with excellence if you want to become an expert. As they say here in Texas, the fruit never falls far from the tree.

So, what’s next for you?

My current focus is to develop a suite of tools that individual investors can use to manage their investments more wisely. The challenge is to make these simple enough for everyone to use yet powerful enough to give them confidence that they will be better off if they proactively manage their investment portfolios.

Giving Day 2020: Stony Brook Strong by the Thousands

Photo above: the Summer Oceanography class from 2018

From Giving Day 2020: Stony Brook Strong by the Thousands on Stony Brook University News, October 16, 2020.

Stony Brook community surpasses Giving Day goal, donating more than $300,000 to 90-plus initiatives across the University

In the span of just 24 hours on October 8, Seawolves came forward in droves to support the areas on campus that matter most to them, from student emergency funds and scholarships to Stony Brook athletics and interdisciplinary research initiatives.

In the span of just 24 hours on October 8, Seawolves came forward in droves to support the areas on campus that matter most to them, from student emergency funds and scholarships to Stony Brook athletics and interdisciplinary research initiatives.

Alumni led the way in donations, making more than 40 percent of the 2,680 gifts to the fundraising drive. Other donors included faculty and staff, friends, students, parents and grateful patients.

It’s inspiring to see the Stony Brook community come together in this remarkable way,” said Stony Brook University President Maurie McInnis. “Even in the midst of exceedingly challenging times, a record number of people stepped up to show their support for Stony Brook and, really, for one another. We’re grateful to everyone who gave so generously. Once again, I’m incredibly proud to call myself a Seawolf.

Donors came from across New York, as well as 41 other states and seven countries. While over $300,000 was raised during Giving Day, the average gift was $97, demonstrating the collective impact that thousands of donors can have on areas across the University.

In the spirit of going far beyond, alumni, friends and faculty created 21 matching gift challenges and 57 donor participation challenges, generating tens of thousands of dollars in additional gifts.

Paul Muite, executive director of annual giving, announced that all gifts received before midnight on October 16 will be counted toward Giving Day. “The response to Giving Day was so remarkable this year. We want to keep that momentum going and make sure everyone has a chance to take part and show the world just how Stony Brook Strong we are.”

As of Monday, October 19. 2020, gifts toward the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences raised $11,065. The SoMAS Total Immersion Scholarship raised $4,005, including a $2,900 matching gift challenge from alum Dr. Alexander Kolker. The Bay Scallop Bowl raised $735. And the Center for Clean Water Technology raised $6,325, which includes a $1,000 matching gift challenge from Dr. Chris Gobler, and a $2,500 from The Susan Haig, DMA Matching Gift Challenge.

Please visit the Giving Day crowdfunding page to make a gift.

SoMAS Faculty Unfolding the Secrets of Ice Formation to Better Understand Climate

From Unfolding the Secrets of Ice Formation to Better Understand Climate on Stony Brook University News, August 8, 2020.

STONY BROOK, NY, August 7, 2020 – Ice crystal formation plays a crucial role in precipitation formation and alters the radiative properties of clouds, thereby affecting Earth’s climate system. In recent years there has been tremendous progress in understanding how liquid-phase droplets are formed (nucleation), yet the nucleation of ice crystals has remained elusive. That’s why Daniel Knopf, PhD, Professor in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) at Stony Brook University, is studying the nucleation of ice crystals with the goal to improve current cloud and climate modeling approaches. The research is supported by a three-year $710,000 grant from the Department of Energy that starts September 15, 2020.

An aerosol sampling stack and inlet tubes at the DOE’s Atmospheric Radiation Measurement Program Site in Oklahoma for studying ice formation from aerosol particles.

“Ice formation is considered one of the remaining grand challenges in the atmospheric sciences,” says Professor Knopf. “The objective of the project is to gain a predictive understanding of the chain that leads from aerosols to ice-nucleating particles to ice crystal number concentrations in clouds.”

He hopes the results of the project will guide concrete improvements in the current cloud and climate modeling approaches to ice formation by advancing understanding of the coupling between detailed aerosol physicochemical properties and in-cloud ice crystal number concentrations. This understanding would ultimately result in better predictions of the climatic impact of ice crystal containing clouds.

The grant (DE-SC0021034) is part of a group of national awards under the DOE’s Atmospheric System Research program.

SoMAS Alum Celebrates Release of First Book

Laurie Zaleski has found a way to communicate her science to new audiences and published her first book. A graduate from the lab of Dr. Roger Flood, she earned her M.S. degree from the Marine Sciences Research Center (now SoMAS) at Stony Brook University in 2002.

A Young Person’s Field Guide to Finding Lost Shipwrecks is Laurie’s autobiographical account of an actual nautical archaeological expedition. The book is written from the surveyor’s point of view and explains the math and science behind multibeam sonars and how to use the technology to find shipwreck. Along the way she describes the equipment used to explore the seafloor. The reader is taken through a typical day at sea on a marine research vessel equipped with a multibeam sonar and ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle) on a real-life expedition in search of a shipwreck. The story begins alongside a dock in Cadiz, Spain with a team that includes Laurie, three archaeologists, two college students on a summer internship, three captains, one cook, one engineer, two SCUBA divers and one able-bodied seaman onboard the Hercules, a 37 meter research vessel and are in the midst of getting ready to set sail in search of the Santisima.

Readers will learn a lot more than science in this true-life account of a scientific expedition. They will learn history, eat tapas, and dance the flamenco all while in search of a 300-year-old shipwreck. Introducing Multibeam and Acoustic Reflectivity to children – What could be better? And women scientists! Yeah!

She says she wrote A Young Person’s Field Guide to Finding Lost Shipwrecks “because of my love of science,” and “moreover my love of my 12-year-old granddaughter and the essential need for all children, especially girls, to keep their sense of adventure firmly intact as well as to find a connection to themselves through math and science.”

Thanks to her time at SoMAS launching her into her career, Laurie has been fortunate to have travelled the world–from the Arctic Circle to Saipan and all points in between conducting geophysical surveys. She has mapped thousands of kilometers by plane, boat and foot. She fondly remembers her time at Stony Brook as a turning point in her life. She had donated a copy of the book to SoMAS as a way to inspire the next generation of brilliant young oceanographers!

Thanks to her time at SoMAS launching her into her career, Laurie has been fortunate to have travelled the world–from the Arctic Circle to Saipan and all points in between conducting geophysical surveys. She has mapped thousands of kilometers by plane, boat and foot. She fondly remembers her time at Stony Brook as a turning point in her life. She had donated a copy of the book to SoMAS as a way to inspire the next generation of brilliant young oceanographers!

The book is available on Amazon in Kindle and Hardcover.

Zaleski, L.A. (2020). A Young Person’s Field Guide to Finding Lost Shipwrecks: The Search for the Santisima. Austin Macauley Publishers.

SoMAS MCP Program Prepares Grad for Influencer Role

Photo above: Alan Alda, center, with Rachael Coccia, left, and her graduate advisor Kate Fullam.

From Master’s Program Prepares Grad for Influencer Role by Glenn Jochum on Stony Brook University News, May 27, 2020.

Helping to clear our shores of unsightly and dangerous plastics is both a mission and a great job for Rachael Coccia ’17, who earned a master’s degree in the Marine Conservation and Policy (MCP) program at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS).

“I was looking for a unique program that would allow me to specialize in communicating about marine conservation topics to bridge the gap among scientists, policymakers and the public,” Coccia said. “The one-year program offered that flexibility.”

Coccia, a resident of San Diego, California, described her time at Stony Brook as “pivotal,” helping her get to where she is today: plastic pollution manager at the Surfrider Foundation, a nonprofit environmental organization that works to protect the world’s oceans and beaches.

In her position, Coccia directs the nationwide Ocean Friendly Restaurants and Beach Cleanup programs from the foundation’s headquarters in San Clemente, California.

Coccia credits her time working as a graduate assistant at the University’s Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science for the development of important skills that she would use in her career.

While there she managed The Flame Challenge, an international competition that challenges scientists to explain complex science concepts in ways that are understandable to an 11-year-old. In that role, she reviewed hundreds of entries from scientists explaining energy to kids.

“Having the chance to work alongside Alan Alda was incredible,” said Coccia. “He’s very involved with the Center and in particular, The Flame Challenge.”

She also enjoyed several courses offered at the Alda Center, including Improv for Scientists.

“This class was very eye-opening as I watched scientists from many different disciplines come together to explore their science and learn techniques to better communicate about what they do,” she said.

Another highlight: taking a video production class at the Alda Center in which she documented a trawl survey and developed a video featuring the work of the Shinnecock Bay Restoration Program.

“We pulled up some incredible specimens, including some adorable puffer fish,” she said.

Coccia’s knowledge of things pelagic came easily to her, even though she grew up in landlocked Rochester, New York. That’s because she was always enamored of the outdoors, spending hours running through the woods and playing in a creek. Later on, she became a lifeguard and competed on her high school’s swim team, earning her the nickname “Fish.”

Her most cherished outings, however, were to the beaches of the East Coast. “I would play in the water for hours on end, search for critters under the rocks and dive down to the ocean floor to enjoy the relative peace beneath the waves,” she recalled.

It was through the MCP program that Coccia connected with the Eastern Long Island chapter of Surfrider.

“That introduced me to the Ocean Friendly Restaurants program,” she said. “I was able to visit restaurants to discuss the program with them, learn of the obstacles they would face and come up with solutions.”

That experience proved vital to her current role as the program’s national director.

The path to Surfrider was a circuitous one, but a bit of luck mixed with persistence landed her a dream job.

Coccia first applied for the position of plastic pollution manager soon after graduating from Stony Brook. She made it to the final round in the interview process but ultimately did not get the job because there were more qualified applicants, she was told.

“It’s a very competitive field to find jobs in because these are the jobs that will ultimately save our planet,” Coccia explained.

So she interviewed for a number of related positions online before changing her approach and getting the experience she needed.

Her new strategy was to set up face-to-face chats with local organizations, which led to her taking a part-time position with The Ocean Project, the global coordinator for World Oceans Day. A full-time position became available in 2018.

As the director of youth initiatives overseeing the World Oceans Day Youth Advisory Council, Coccia was able to work remotely before moving across the country to San Diego. Nearly a year after she moved, she saw another posting for the plastic pollution manager position at Surfrider. She interviewed for it this time in person — and landed the job.

Before she enrolled at Stony Brook, Coccia earned a bachelor’s degree in public relations at Fredonia State University, and hosted an associate-produced 40 episodes of the Aqua Kids TV Series, an Emmy award-winning K–12 program that educates young people about ecology, wildlife, science and how it relates to them.

That experience reinforced her commitment to communicating about the crisis caused by plastic pollution — and the outrage she felt learning about the mistreatment of the ocean. The images of marine life tangled in plastic seared into her brain during an undergraduate environmental science class.

Today, she consults with the inaugural Surfrider Club Leadership Council to encourage more involvement and integration with its 100-plus student clubs across the nation.

“The solutions already exist — it’s just a matter of scaling them up and implementing them on a larger scale,” Coccia said.

She said there are approximately 630 Ocean Friendly Restaurants across the country that have committed to using reusables only for on-site dining, avoiding plastic bags and straws, and instituting other plastic-free policies.

Coccia said some people avoid single-use plastics by arming themselves with reusable alternatives, from cups and bags to straws and containers. For those looking to remove all single-use plastics from their lives, there are DIY hackathons that offer instruction on how to make soap, toothpaste, cleaners and more in reusable containers.

“The problem is that it shouldn’t be up to individuals. The plastics industry and larger corporations that profit from plastic put us in this mess, and they should be held responsible to help us out,” Coccia said. “When we can hold them accountable through policies like extended producer responsibility, that’s when we’ll truly be able to leave our toxic addiction to plastic in the past.”

#SeawolvesForLife

SoMAS Grad Student Selected for Competitive Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship

From SBU Grad Student Selected for Competitive Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship on Stony Brook News, December 17, 2019.

Irvin Huang, a PhD candidate in the Stony Brook University School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, has been chosen as a fellow in the John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship program, which matches highly qualified graduate students with “hosts” in the legislative branch, executive branch, or appropriate associations/institutions located in the Washington, DC area, for a one-year paid fellowship. The program is sponsored by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Sea Grant College Program.

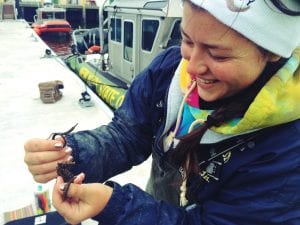

Huang is on the executive path and is slated to work in non-legislative offices in Washington, DC, beginning in February 2020. At Stony Brook he works in the Aquatic Toxicology Lab of Professor Anne McElroy, where he uses molecular biology to understand the impacts of pollutants on fish health and survival.

“I’m very excited and honored to have been selected for the Knauss Fellowship,” said Huang. “While I admit that policy was not my original goal when I started graduate school, I’ve since realized the vast potential that public and environmental policy has for creating science for the people. My life goal has always been to use science to help improve society, and I’m confident that I can do that by bringing my scientific training into a policy setting through the Knauss Fellowship. I’m excited to learn how to develop policy that is informed by the most recent research, which will hopefully be broadly applied to help the most people possible.”

For more details about the program, visit the National Sea Grant College Program’s website at www.seagrant.noaa.gov/Knauss.

Substantial Natural History Collection Gifted to SoMAS

Photo above: the Research Vessel Seawolf conducting a cruise on the Hudson River.

From Extraordinary Collection of Marine Specimens and Data Donated to University on SBU News, December 6, 2019

Gift provides a windfall of unpublished biological and water quality data for 43 years of Hudson River sampling, including preserved specimens.

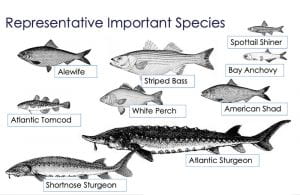

An extraordinary scientific collection of fish specimens, as well archived fish and water quality data taken from the Hudson River over more than five decades, has been donated to Stony Brook’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS).

What is now known as the Hudson River Collection (the Collection), donated to the university by the integrated energy company, Entergy Corporation (Entergy), began in the 1960’s as “one of the most ambitious environmental research and assessment programs ever performed” on an iconic River that was a focal point for the nascent U.S. environmental movement. As it grew, the Collection became unique, variously referred to as “probably the best dataset on the planet,” “unequalled globally in its duration and its spatiotemporal frequency” and “extraordinarily important, because it provides a retrospective and unbroken view of the ecological health of the estuary over time.”

The Long River Beach Seine survey, begun in 1974, is among many unique scientific samplings represented in the Hudson River Collection.

The Collection includes Indian Point-sponsored, digitized survey data for the full complement of fish species (approximately 170) available to the sampling gear in the approximately 150-mile Hudson River Estuary (from the Battery to the Troy Dam), and the associated water quality and Indian Point-specific biological information. The Collection also includes the associated archived fish specimens, consisting mostly of preserved early life stages of Estuarine fish, numbering approximately 50 million individuals. The database is unequalled, and the specimens from the Collection represent among the largest held by any U.S. museum or university, placing Stony Brook among a handful of renowned institutions, such as the Smithsonian.

Entergy also has made a substantial donation of seed capital to advance Stony Brook’s goal of groundbreaking scientific study related to the Collection – study that dovetails with SoMAS’s expertise on coastal, marine, estuarine ecosystems, including biodiversity, population genetics, climate change and disease. The Collection’s digitized databases make them readily usable “big data,” susceptible to the cutting-edge statistical methods and advanced computing on which Stony Brook excels.

“This donation positions Stony Brook as a leader in developing innovative forms of multidisciplinary science endeavors,” said Michael A. Bernstein, Interim President of Stony Brook University. “I am confident that our unparalleled access to the Hudson River Collection will result in extraordinary research opportunities.”

“We want to thank the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and leading scientists for supporting us in our search for the right home for the Collection,” said Mike Twomey, Senior Vice President, Federal Policy, Regulatory and Government Affairs for Entergy. “SoMAS and Stony Brook are the right home for an unparalleled Collection, one that we could not be more pleased to give.”

Paul Shepson, Dean of SoMAS, echoed those thanks, underscoring that the Collection will not only advance SoMAS’s standing as a leading research and educational institution, but enable scientists and their students to better understand a wide range of subjects, beginning with the environmental drivers within the Hudson River ecosystem and aquatic ecosystems in general.

“The Collection’s data and samples will enable leading scientists to develop collaborative and interdisciplinary research projects, leading to new discoveries that will be instrumental in understanding changes in estuarine and marine environments both locally and worldwide,” said Shepson. “We are both excited and grateful to Entergy for entrusting Stony Brook with such an incredible and unprecedented collection.”

###

About Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University, widely regarded as a SUNY flagship, is going beyond the expectations of what today’s public universities can accomplish. Since its founding in 1957, this young university has grown to become one of only four University Center campuses in the State University of New York (SUNY) system with over 26,000 students, more than 2,700 faculty members and 18 NCAA Division I athletic programs. Our faculty have earned numerous prestigious awards, including the Nobel Prize, Pulitzer Prize, Indianapolis Prize for animal conservation, Abel Prize and the inaugural Breakthrough Prize in Mathematics. The University offers students an elite education with an outstanding return on investment: U.S. News & World Report ranks Stony Brook among the top 40 public universities in the nation. Its membership in the Association of American Universities (AAU) places Stony Brook among the top 62 research institutions in North America. As part of the management team of Brookhaven National Laboratory, the University joins a prestigious group of universities that have a role in running federal R&D labs. Stony Brook University fuels Long island’s economic growth. Its impact on the Long Island economy amounts to $7.38 billion in increased output. Our state, country and world demand ambitious ideas, imaginative solutions and exceptional leadership to forge a better future for all. The students, alumni, researchers and faculty of Stony Brook University are prepared to meet this challenge.

About SoMAS

SoMAS is the State University of New York’s designated center for marine sciences and a leader in marine, atmospheric and sustainability research, education, and public service. Currently, there are more than 500 undergraduate and graduate students and 90 faculty and staff from 16 different nations working together to better understand how our marine, terrestrial, and atmospheric environments function, are related to one another and how they and their associated living resources may be sustained for future generations. Research at SoMAS explores solutions to a variety of issues facing the world today ranging from local problems affecting the area around Long Island to processes that are impacting the entire globe.

About Entergy Corporation

Entergy Corporation (NYSE: ETR) is an integrated energy company engaged primarily in electric power production and retail distribution operations. Entergy owns and operates power plants with approximately 30,000 megawatts of electric generating capacity, including 9,000 megawatts of nuclear power. Entergy delivers electricity to 2.9 million utility customers in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. Entergy has annual revenues of $11 billion and approximately 13,500 employees. Additional information is available at entergy.com.

High-Tech Instruments at SoMAS Empower the Search for Microplastics

From High-Tech Instruments Empower the Search for Microplastics by Glenn Jochum on Stony Brook News, November 1, 2019

It’s an invisible problem on a global scale.

Drinking straws, shopping bags and other plastic litter contaminating our beaches and oceans are easy to see, but true microplastics – particles ranging in size from 5 millimeters to those too tiny for the unaided human eye to perceive – are entering the food chain, potentially causing damage to marine animals and human bodies.

That’s why researchers in Gordon Taylor’s lab at Stony Brook’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) are searching for these unseen ocean contaminants with the help of two high-powered instruments.

SoMAS’ microplastics research team selecting field samples to be analyzed on the laser Raman microspectrophotometer (pictured in the background) which is housed in the NAno Raman Molecular Imaging Laboratory. (L-R) Professor Gordon T. Taylor (PI), Ms. Tatiana Zaliznyak (research support specialist), and Mr. Luis Medina Faull (Ph.D. student).

Students and research associates are using a laser Raman microspectrophotometer to help them explore the chemical composition of microplastics that pose a global threat to marine environments, and an atomic force microscope that can image molecules and the tiniest of organisms.

“To the best of my knowledge, we are the only environmental or marine science lab in the United States to have such capable instruments, aside from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts,” said Taylor, a Professor of Oceanography at SoMAS and Director of the NAno-Raman Molecular Imaging Laboratory (NARMIL).

In simplified terms, the microspectrophotometer is a laser-based device that measures the colors of light scattered from sample materials and provides chemical information. The Raman instrument is capable of focusing a laser beam down to a third of a micrometer, which is 200 times less than the width of a human hair.

The atomic force microscope is capable of resolution down to a tenth of the width of a single DNA molecule, which enables visualization of proteins and the surface of cells and viruses.

With these tools, Taylor said, researchers can produce three-dimensional chemical maps; software then reconstructs the images in a process similar to how medical tomography interprets a CT scan.

As technology evolves, Taylor emphasized, researchers increasingly require significant funding to invest in the equipment necessary for meaningful results. “Basic research involves constant auditioning to get money,” he said.

Taylor’s Ph.D. student, Luis Medina, is studying samples taken from New York Harbor out into the Atlantic, off the Long Island coast, as well as in the Arctic, Antarctic, Caribbean Sea and the coast of Mexico. Medina has also been working on a National Geographic grant investigating microplastics in the coastal waters of his native Venezuela with help from research support specialist Tatiana Zaliznyak. Their work is in its early stages.

“For my research, I am very fortunate to have access to a confocal Raman microspectrophotometer,” Medina said. “This technology is unmatched for exploring small-scale interactions among microplastics, microorganisms and the environment. Understanding these interactions is fundamental to addressing unanswered questions about effects of microplastics pollution in our oceans.”

According to Taylor, the jury is out on whether or not ingesting microplastics poses a serious health risk. The concern is that microplastics can potentially concentrate other contaminants such as dangerous hydrocarbons, pesticides, and PCBs, which are known to be absorbed by plastics.

“We know that many types of marine animals concentrate plastic contaminants from their environment,” he said. “Microplastics can act as vehicles for harmful chemicals to move up the food chain. The technology being developed in NARMIL will provide a means to improve our understanding of microplastics behavior in the ocean.”

“As an analytical and environmental chemist, I am delighted to see this very clever combination of Raman spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy applied to the pursuit of a significant contemporary environmental problem, said SoMAS Dean Paul Shepson.

“Professor Taylor’s group is leading the world toward a better understanding of human impacts on the Earth’s oceans,” Shepson said.

New Study Reveals Important yet Unprotected Global Ocean Areas

From New Study Reveals Important yet Unprotected Global Ocean Areas on Stony Brook News, October 25, 2019.

The published findings may guide policymakers to increase MPAs

STONY BROOK, NY, October 25, 2019 — The largest synthesis of important marine areas conducted to date reveals that a large portion of earth’s oceans are considered important and are good candidates for protection. A first of its kind, the study was conducted by a multidisciplinary team of researchers including Ellen Pikitch, PhD, and Christine Santora of Stony Brook University and Dr. Natasha Gownaris, a PhD graduate of Stony Brook University. The team examined 10 diverse and internationally recognized maps depicting global marine priority areas. The findings, published in Frontiers in Marine Science, may serve as a roadmap for the goal set by the United Nations to create 10 percent of the ocean as marine protected areas (MPAs) by 2020.

There are numerous ongoing United Nations and nongovernmental initiatives to map globally important marine areas. Such areas may be identified because of their high biodiversity, threatened or vulnerable species, or relatively natural state. Criteria used for mapping vary by initiative, resulting in differences in areas identified as important. This paper is the first to overlay mapping initiatives, quantify consensus, and conduct gap analyses at the global scale.

The analysis found that 55% of the ocean has been identified as important by at least one of the mapping initiatives (58% of this area is within national jurisdiction and 42% is in the high seas). More than 14% of the ocean was identified as important by between two and four maps, and a gap analysis showed that nearly 90% of this area is currently unprotected. The largest of these important but unprotected areas were located in the Caribbean Sea, Madagascar and the southern tip of Africa, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Coral Triangle region. Nearly all area identified by five or more maps is already protected as reported by the World Database on Protected Areas. Most (three quarters) nations protect less than 10 percent of the identified priority areas within their exclusive economic zones (EEZs).

“An enormous area of the ocean has already been identified as important by scientists and conservationists but remains unprotected,” said Pikitch, Endowed Professor of Ocean Conservation Science in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (SoMAS) at Stony Brook University. “Opportunities for further ocean conservation are widespread and include areas within the national jurisdictions of most coastal states as well as the high seas.”

This map depicts areas of the ocean globally deemed important by 1 (lightest green) and 7 (darkest green).

Based on the team’s analysis of the 10 maps, Pikitch explained that the goal to protect 10 percent of the oceans by 2020 could be met solely through the actions of coastal states. If all the unprotected ocean area identified as important by two or more initiatives were to be protected by 2020, an additional 9.34 percent of the ocean would be added to the global MPA network.

In addition, more than 76 million km2 of areas beyond national jurisdictions were identified as important and unprotected. This finding, she added, may therefore inform ongoing discussions about protection of the high seas.

The investigators also used biogeographic classification to determine whether current protection of important areas was ecologically representative. They found it was not, as only half of all 99 ocean provinces protect at least 10 percent of their identified area. This, they point out, suggests the need for improvement in creating an ecologically representative global MPA network.

“This study can help guide placement of future MPAs to meet agreed objectives for the quantity, quality and representativeness of the global network of marine protected areas,” Pikitch emphasized. “Local studies and expertise will also be necessary to implement this process.”

###

About Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University, widely regarded as a SUNY flagship, is going beyond the expectations of what today’s public universities can accomplish. Since its founding in 1957, this young university has grown to become one of only four University Center campuses in the State University of New York (SUNY) system with over 26,000 students, more than 2,700 faculty members and 18 NCAA Division I athletic programs. Our faculty have earned numerous prestigious awards, including the Nobel Prize, Pulitzer Prize, Indianapolis Prize for animal conservation, Abel Prize and the inaugural Breakthrough Prize in Mathematics. The University offers students an elite education with an outstanding return on investment: U.S.News & World Report ranks Stony Brook among the top 40 public universities in the nation. Its membership in the Association of American Universities (AAU) places Stony Brook among the top 62 research institutions in North America. As part of the management team of Brookhaven National Laboratory, the University joins a prestigious group of universities that have a role in running federal R&D labs. Stony Brook University fuels Long island’s economic growth. Its impact on the Long island economy amounts to $7.38 billion in increased output. Our state, country and world demand ambitious ideas, imaginative solutions and exceptional leadership to forge a better future for all. The students, alumni, researchers and faculty of Stony Brook University are prepared to meet this challenge.

Additional Coverage

Times Beacon Record: SBU’s Ellen Pikitch reveals ways countries can meet ocean saving target

Hakai Magazine: Where Should the World Focus Its Ocean Conservation Efforts?

WSHU: By Mapping Oceans, Scientists Identify Areas Most In Need Of Protection

Laura Klahre ’97 Defends Long Island’s Native Pollinators

Bee rancher Laura Klahre sits by her mason bee cottages at Blossom Meadow Farm in Southold. Photo by Randee Daddona

From Laura Klahre ’97 Defends Long Island’s Native Pollinators on Stony Brook Matters by Kristen Temkin Brennan

Laura Klahre ’97 speaks for the bees.

As a bee rancher and the owner of Blossom Meadow Farm on the North Fork of Long Island, no one understands the importance of pollinators more than Klahre. That’s why she works hard to educate the public on creating friendly environments for bees.

But not all bees are created equal. While recent headlines have drawn attention to honey bees, the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences alumna is working hard to shift attention to Long Island’s native pollinators, including mason bees and bumblebees, both of which pollinate two to three times better than the invasive honey bee.

As a School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences graduate, you began your career as an oceanographer. What inspired your career change to bee rancher and berry farmer?

Life is definitely a meandering path but the leap from oceanography to farming is not as gigantic as one would think. Similar ecological principles for healthy ecosystems apply on land and underwater. For example, biodiversity is critical for a stable ecosystem when dealing with the fisheries in the Atlantic, the resiliency of a coral reef, and even for a self-sustaining farm. To this end, we maintain a tract of grassland and natural areas for native pollinators to live, follow organic growing principles, ensure multiple flower species are blooming throughout the growing season, turn off the lights at night (moths pollinate), and no longer keep honey bee hives.

Life is definitely a meandering path but the leap from oceanography to farming is not as gigantic as one would think. Similar ecological principles for healthy ecosystems apply on land and underwater. For example, biodiversity is critical for a stable ecosystem when dealing with the fisheries in the Atlantic, the resiliency of a coral reef, and even for a self-sustaining farm. To this end, we maintain a tract of grassland and natural areas for native pollinators to live, follow organic growing principles, ensure multiple flower species are blooming throughout the growing season, turn off the lights at night (moths pollinate), and no longer keep honey bee hives.

You’re currently working to ban honey bee hives from protected lands. Can you tell us more about why this is such an important initiative? How are honey bees impacting our ecosystem?

Declining honey bee populations have gripped the headlines and unfortunately spurred many land managers to allow hives on protected lands. Receiving a fraction of the media attention, native bee populations have been hit even harder and are ecologically more important. A multitude of papers have shown that honey bees outcompete native bees for food, change the ecosystem by preferentially pollinating invasive weeds, and can transmit pathogens and parasites to native bee species. Honey bee hives should be banned from parklands and open space in order to protect resident native bee populations and overall ecosystem health.

In a similar vein, sustainability programs should not teach beekeeping. In light of the most recent research findings, beekeeping should only be taught as part of an agricultural program. Honey bees should be seen as livestock and appropriate to pollinate large scale, single crop agriculture where pesticides are heavily relied upon, there is little to no natural habitat set aside and pollinator availability is a problem.

You mentioned the importance of learning about sustainability practices. How has Stony Brook prepared you for your work today?

Before my first day of graduate school, I had never been to Long Island. Yes, I grew up on the shore of New Jersey and had been to New York City several times, but never to Long Island. Once you find your groove, it is a fascinating place! Although close to an urban center, nature still abounds and the North Fork of eastern Long Island still has strong agricultural underpinnings. Sustainable agricultural practices are critical for nutritious crops, bountiful yields, and for a healthy environment.

My graduate years at Stony Brook University were hard, but the research and classes prepared me for this path forward. I love reading journal articles about native pollinators (Dr. John Ascher and Dr. Bryan Danforth are two of my favorites) and figuring out how to take the science and bring it into practice. For example, deformed and misshapen fruit likely results from a pollination problem. Native bees, like mason bees and bumblebees, pollinate 2-3 times better than the non-native invasive honey bee. Science has shown that more complete pollination of a flower results in heavier, higher quality fruit and thus a higher crop yield per acre. We started ranching mason bees on our farm years ago and now over 150 people have started with mason bees through us (one can sign up for our newsletter through blossommeadow.com). Although I kept honey bees since the late 1990’s, those hives are now gone.

Tell us more about your work at Blossom Meadow Farm.

We are a small farm in Southold, NY focused on growing premium berries, making great jam, and raising mason bees. We are particularly well known for our award-winning red raspberry and strawberry jams. We don’t use commercial pectin to make jam. Instead, the jam is thickened by allowing the fruit to slowly reduce, coaxing out the fruit’s vibrant flavors and natural pectin.

Our tagline is Eat Jam, Save Nature. Jam sales support the farm as well as our side conservation initiatives with monarch butterflies, nocturnal pollinators, and now carbon sequestration efforts by growing and planting oak trees.

What does a typical day look like for you?

My husband, Adam Suprenant, is a winemaker, and together we co-own the winery Coffee Pot Cellars (named for the Orient Point Lighthouse, which sailors call the “Coffee Pot”). Blossom Meadow Farm shares retail space with the Coffee Pot Cellars Tasting Room in Cutchogue. A typical day during the warm months entails picking fruit in my pajamas while listening to an audiobook. At 11 am, my black pug Beasley and I zoom down the road about three miles to open up the tasting room. We pour wine and talk conservation all day and then head back to the farm at 6 pm to pick more fruit until dark. We are closed on Tuesdays and Wednesdays so that I can make jam.

How about a typical day off?

With the farm in full production, there really is no day off but I love what we do. One of the clear benefits to living on Long Island though is that there is always a beach within bicycling distance to take a quick dip.

In your 2015 TED Talk, you spoke about the critical role that bees play in food production. What is one thing you wish everyone knew about native pollinators?

Planting bee-friendly plants adds color to your landscape AND helps reconnect Long Island’s fragmented natural areas to form larger more diverse ecosystems. Planting bee-friendly plants, shrubs, and trees creates a vibrant wildlife corridor for bees, butterflies, birds, and other creatures. Instead of driving somewhere to see nature, you can bring nature to your doorstep.

For more information on bee-friendly plants, Laura Klahre and Blossom Meadow Farm, please visit blossommeadow.com or follow them on Instagram and Facebook.

Learn more about how Stony Brook is building a bee-friendly campus.

Koppelman Documentary Premiere

Photo above: Documentary film creators Anna Smith and Megan Gallagher with Dr. Lee Koppelman

SoMAS undergraduate students Megan Gallagher, an Environmental Humanities Major with a Biology Minor, and Anna Smith, an Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Major with an Environmental Humanities minor premiered their documentary about Long Island Urban Planner and Stony Brook University Professor Emeritus Lee Koppelman on Friday September 20, 2019 in Endeavour Hall Room 120. As previously noted, Dr. Koppelman “played an immense role in balancing planned growth and environmental preservation in one of the fastest growing regions in the United States” as director of the Suffolk County Planning Department for 28 years (1960-1988) and the Nassau-Suffolk County Regional Planning Board executive director for 41 years (1965-2006).

Dean Paul Shepson was the emcee for the evening, welcoming a full house to the event, including family and friends of Dr. Koppelman, Brookhaven Town Councilwoman Valerie M. Cartright, and Muriel Weyl, widow to SoMAS professor Peter Weyl. After Dean Shepson introduced student mentors Dr. David Taylor, faculty advisor of Environmental Humanities, and Mark Lang, Senior Systems Engineer at SoMAS, Anna and Megan introduced their film. The documentary focuses on Dr. Koppelman’s legacy on Long Island, tying together the history of expansion on post-war Long Island with Dr. Koppelman’s efforts at preservation. The interviews with Dr. Larry Swanson, Dr. Tara Rider, Dr. Dewitt Davies, and Richard Murdocco connect the story to educational mission of Stony Brook University.

The film is available to view on YouTube and Facebook.

After the premiere of the film, SoMAS Dean Shepson conducted a Question and Answer panel with the creators of the film, Megan Gallagher and Anna Smith, along with their mentors Dr. David Taylor and Mark Lang, and all the “stars” of the film: Dr. Lee Koppelman, Dr. Tara Rider, Dr. Larry Swanson, Dr. Dewitt Davies and Richard Murdocco. Video from the event is available on YouTube.

Photos from the Premiere taken by Maria Brown are available on Google Photos.

Related articles:

SoMAS Researcher Investigates New Modeling Technology to Assess Climate Change Impact on Winter Storms

Photo above: Image of a bomb cyclone that brought heavy snow and strong winds to the U.S. East coast during January 2018. Professor Chang’s research will explore how these cyclones and their impact will change in a warming world. Credit: NOAA

From Researcher Investigates New Modeling Technology to Assess Climate Change Impact on Winter Storms on Stony Brook News, October 3, 2019

STONY BROOK, NY, October 3, 2019 — Winter storms result in substantial loss of life and property. Scientists are investigating how these extreme winter weather events that cause damage are influenced by climate change.

Edmund KM Chang, PhD, a Professor in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) at Stony Brook University, has received a two-year $200,000 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Modeling, Analysis, Predictions and Projections program (NOAA/MAPP) to look more closely at the interactions between diabatic heating and storm dynamics to assess how warming temperatures will impact major snowstorms and winter floods.

Edmund KM Chang, PhD, a Professor in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) at Stony Brook University, has received a two-year $200,000 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Modeling, Analysis, Predictions and Projections program (NOAA/MAPP) to look more closely at the interactions between diabatic heating and storm dynamics to assess how warming temperatures will impact major snowstorms and winter floods.

Recent studies have suggested that previous versions of Global Climate Models (GCMs) may not have sufficient resolution to correctly simulate the interactions between diabatic heating and storm dynamics, potentially under-estimating the intensity of these storms in future projections.

Professor Chang says his project will study these storms using, for the first time, multi-model ensemble projections that have resolution high enough to define and better simulate these interactions. He contends the results of the research will provide better understanding on how these hazards will change in the future.

###

About Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University is going beyond the expectations of what today’s public universities can accomplish. Since its founding in 1957, this young university has grown to become a flagship as one of only four University Center campuses in the State University of New York (SUNY) system with more than 26,000 students and 2,600 faculty members, and 18 NCAA Division I athletic programs. Our faculty have earned numerous prestigious awards, including the Nobel Prize, Pulitzer Prize, Indianapolis Prize for animal conservation, Abel Prize and the inaugural Breakthrough Prize in Mathematics. The University offers students an elite education with an outstanding return on investment: U.S. News & World Report ranks Stony Brook among the top 50 public universities in the nation. Its membership in the Association of American Universities (AAU) places Stony Brook among the top 62 research institutions in North America. As part of the management team of Brookhaven National Laboratory, the University joins a prestigious group of universities that have a role in running federal R&D labs. Stony Brook University is a driving force in the region’s economy, generating nearly 60,000 jobs and an annual economic impact of more than $4.6 billion. Our state, country and world demand ambitious ideas, imaginative solutions and exceptional leadership to forge a better future for all. The students, alumni, researchers and faculty of Stony Brook University are prepared to meet this challenge.

About the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences

The School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) is a leader in marine, atmospheric and sustainability research; education; public service; and is SUNY’s designated center for the marine sciences. The School is among the leading oceanography and atmospheric sciences institutions in the world, providing students with access to state-of-the-art research laboratories, shipboard experiences, high-powered radar and computing facilities. SoMAS provides expanded study opportunities in the fields of ocean conservation, climate change and extreme weather, sustainability, waste management, marine fisheries and resources, and many others.

Stony Brook Celebrates as Ashley Schiff Preserve Turns 50

From Stony Brook Celebrates as Ashley Schiff Preserve Turns 50 on Stony Brook News on October 3, 2019 by Glenn Jochum

Some students know it as a scenic shortcut from the Main Campus to South Campus and back. Others use it as a “living laboratory” to study its geographical features and learn about its rich plant and animal life. For the whole community, it’s a place of enduring natural beauty.

The 26-acre Ashley Schiff Preserve turns 50 this year. This week Stony Brook will pay tribute to its past and underscore its importance for future generations.

The preserve was created by the University’s first president, John Toll, along with former U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, in honor of Ashley Schiff, a beloved political science professor and environmental activist. Schiff, who died unexpectedly in 1969 at the age of 37, was known for his dedication to teaching and was voted among the top five best-liked professors on campus in 1968.

Apart from its beauty, the preserve’s educational value is exceptional. It is part of the curriculum for biology, geology, sustainability studies and Women in Science and Engineering, and it is often the first experience many urban students have with seeing birds and mammals in a wild habitat.

“I brought students from the Bronx and Brooklyn and for them, seeing their first deer was like seeing a unicorn,” said Sharon Pochron, a lecturer in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) and current president of the Friends of Ashley Schiff.

Seventy-five species of plants, including trailing arbutus, mountain laurel, winterberry and spotted wintergreen, are native to the deciduous forest. In a five-minute walk from Circle Drive south on the trail, three species of ferns, the ubiquitous maple leaf virburnum, and the colorful, edible mushroom known as Chicken of the Woods were all spotted on a late September day.

“Stepping into that forest is like going back in time,” said Pochron. “There are very few invasive plants — only a limited number of Norway maples or Oriental bittersweet, for example.”

Pochron recalls her astonishment at spotting an American chestnut tree, a species commonly thought to be extinct. “I looked from the leaves to the plant guide and back, certain that I was wrong. The tree was 30 feet tall!”

Animal life abounds as well. Cooper’s hawks, great horned owls, red fox, possums, raccoons and deer are among the fauna sighted from time to time.

“The Ashley Schiff Preserve, which is on the Harbor Hill moraine, has exceptional glacial features including small ridges and valleys as well as kettle holes,” said Gilbert Hanson, Distinguished Service Professor, Department of Geosciences. “The ridges and valleys were formed by the advancing glacier as it pushed sand, gravel and ice in front of it like a bulldozer. The glacier then left a thin layer of till, including numerous boulders, as it overrode the ridges and valleys. Kettle holes in the preserve formed as a result of the melting of the ice below the till.”

“We hope to increase the level of awareness of Ashley Schiff through different events and more accurate social media use, said Hogyeum Evan Joo, ’19, who made the preserve as the subject of his honor’s thesis.

Aside from its scientific allure, the forest has also inspired artistic creativity at Stony Brook. Graduate student Jay Loomis composed and performed one of his own musical compositions under its canopy. On October 2, students and faculty donned “wearable art” embodying forest spirits and led a procession to the preserve during Campus Lifetime.

Stony Brook, NY; Stony Brook University: Friends of Ashley Schiff Park members (Sitting L-R) Karen Warren, Maureen Murphy, Dorothy Schiff-Shannon, Sue Avery, (Standing L-R) Sharon Pochron, Donna DiGiovanni, Melissa Kelly, Lauren Donovan, Michael Schrimpf, and Paul Siegel

A tour highlighting the preserve’s history, geology and unique ecosystem begins at 12:00 noon October 4. A 50th Anniversary celebration is slated to begin at 5:30 pm in the Charles B. Wang Center.

What makes Ashley Schiff even more precious is its rarity. According to Pochron, few universities contain their own designated nature preserves. Only 15 of 66 SUNY campuses have protected areas; only two of the eight Ivy League schools do.

Schiff’s widow, Dorothy Schiff-Shannon, said of the preserve: “It was inspired in grief and shock but his name is appropriately remembered. The students wanted a preserve instead of a building. When President Toll came to our home to tell us about the forest dedication, there was no wink and a nod. It was a handshake and a promise. He meant for the woods to remain wild in perpetuity.”

Stony Brook Know-How Helps to Protect Long Island’s Water Supply

Photo above: Frank Russo delivers a rundown on Stony Brook University’s Wastewater Research and Innovation Facility.

From Stony Brook Know-How Helps to Protect Long Island’s Water Supply on Stony Brook News by Rob Emproto on August 30, 2019.

There are now about 250,000 cesspools in place in Suffolk County, and another 100,000 Suffolk properties deploy septic systems.

“That’s not a good thing,” said Frank Russo, associate director for wastewater initiatives at the Stony Brook Center for Clean Water Technology. “We’re dumping sewage into the ground, and that eventually makes its way to the groundwater.”

It’s an urgent problem that Stony Brook scientists are helping to fix.

“Long Island relies on groundwater as our only option for drinking water,” said Christopher J. Gobler, professor in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences and director of the Center for Clean Water Technology.

“Given trends in surface and groundwater quality since the late twentieth century, it is clear changes are needed to ensure the long-term sustainability of clean water for Long Island,” Gobler said. “The Center for Clean Water Technology will continue to partner with state and local governments and industry to being these changes via innovative solutions.”

Chemically speaking, the culprit is nitrate, an inorganic compound that occurs under a variety of conditions in the environment, both naturally and synthetically. Nitrate is one of the most common groundwater contaminants in suburban areas, and is regulated in drinking water primarily because excess levels can cause methemoglobinemia, or “blue baby” disease.

Nitrate in groundwater originates primarily from septic systems, and from items commonly found in any household – soaps, shampoos, cleaners, pharmaceuticals, and many other products. Though these wastes are deposited deep in the ground, they eventually seep up. On Long Island, that means the nitrate ends up in places like Great South Bay, Peconic Bay, and the Long Island Sound, which feed the Island’s drinking water supply.

That decades-long legacy of nitrogen-rich waste moving from homes to the ecosystem has contributed to the creation of harmful algal blooms, a decrease in the shellfish population, and lower oxygen levels in Long Island’s surface waters, including its bays, rivers and the Sound.

“Do you remember the problems Florida had with its water?” asks Russo, referring to the harmful and well-documented algal blooms the state experienced in 2018. “Long Island is not too far away from that.”

To help combat the problem, Stony Brook is working to develop technology that will remove nitrogen before it can reach the groundwater. The initiative, dubbed “10/10/30,” aims to develop technology that can get the nitrate levels down to 10 mg/liter in a system that costs no more than $10,000 and has a lifespan of at least 30 years.

“We are pilot testing a version of this system, but the current version is too land-intensive for Long Island, which has many plots of ¼-acre or less,” explained Russo. “We need to understand the process, apply existing theories and combine it with our research to get it to a point where it’s viable.”

To facilitate the necessary research, the Center for Clean Water Technology operates a state-of-the-art Wastewater Research & Innovation Facility (WRIF) for the purpose of developing an affordable onsite wastewater treatment system that reduces total nitrogen to less than 10 mg/L prior to groundwater discharge. The facility is a working laboratory that utilizes domestic sewage collected at the Suffolk County Sewer District No. 10 pumping station for actual use within the facility. These systems are intended eventually to replace archaic cesspools that provide virtually no treatment for nitrogen.

Unfortunately, nitrates present just one challenge. Another contaminant becoming more common in Long Island’s groundwater is a compound called 1,4-dioxane, which is a waste product resulting from the manufacturing processes that were pervasive during Long Island’s industrial heyday. Stony Brook is currently providing grant support to test an advanced oxidation process to combat this challenge.

“If regulation kicks in, public water supplies will need to meet the new standards,” warns Arjun Venkatesan, associate director for drinking water at the Stony Brook Center for Clean Water Technology. “If that happens, that means that more than 200 water treatment facilities on Long Island will need to be upgraded at a cost of more than $1 million per system.”

Venkatesan’s cost estimate is significantly more conservative than the roughly $300 million cost estimated by New York’s Department of Health (NYDOH) in 2018. And to illustrate the extent of how unknown the cost of such regulation might be, the NYDOH’s number is less than half of the astounding $840 million the Long Island Conference, a group of water professionals that focus on keeping Long Island’s water supply safe and plentiful, says it would cost to add treatment systems to the 185 drinking water wells contaminated by 1,4-dioxane, according to a Newsday report in February 2019.

Though drinking water cleanliness is an important driver in this research, there’s another potentially catastrophic danger that’s growing; Long Island’s wetlands are disappearing. The wetlands absorb tidal surges, serving as an important barrier during hurricanes. The devastating effects of this erosion were realized in 2012 when Hurricane Sandy ravaged the East Coast and caused an estimated $19 billion of damage to New York City and the surrounding areas, including Long Island.

With the damages of Sandy still being felt by many seven years later, efforts are moving ahead in earnest. There is currently one pilot system running full-scale in Suffolk County, though any wide-scale solution is still years away.

“There are important questions that need to be answered,” said Venkatesan. “We’re trying to attach emerging contaminants and others that are not currently regulated. We need to develop a fundamental understand of the chemical transformation and any potential by-products and figure out the best way to move forward.”

Bassem Allam Invested as Inaugural Marinetics Endowed Professor

Photo above: Bassem Allam was formally invested as the Marinetics Endowed Professor of Marine Science in Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) on April 26. From left to right: Bassem Allam, SoMAS Dean’s Council Chair Bob Maze, Stony Brook Foundation Vice-Chair Laurie Landeau, and Interim Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Minghua Zhang.

From Bassem Allam Invested as Inaugural Marinetics Endowed Professor on Stony Brook News, August 6, 2019 by Elliot Olshansky

Laurie Landeau and Robert Maze continue to support vital research at Stony Brook

What does it mean to be an endowed professor?

For Bassem Allam, formally invested on April 26 as the Marinetics Endowed Professor in Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS), it means the freedom to follow his instincts as a scientist, pursuing knowledge that can help protect and restore marine resources without worrying about securing funding.

“Having this endowment has really allowed me — and, by extension, my graduate students — to take more risks in our research,” Allam said of his endowed professorship, “knowing that we have funding to repeat an experiment, or to do more work than was scheduled in any grants we have.”

Allam’s research is centered on interactions between marine mollusks and waterborne microorganisms in general and, in particular, the framework of host-pathogen interactions. Specifically, Allam has done extensive work with clams and their reactions to Quahog Parasite Unknown (aka “QPX”), a protozoan microbe that affects clams in waters from eastern Canada to the Mid-Atlantic region, and severely impacted New York clam harvests in the 2000s. In recent years, Allam has found funding from the endowed professorship invaluable to his efforts, illustrating the importance of endowed professorships for his research and other scientific endeavors.

“For years,” Allam said, “we didn’t understand how the clam responds to the infection. With the endowment providing additional resources, we were able to sequence the genome of the hard clam. We didn’t have any grant money to do it.

With the genome sequenced, Allam and his colleagues are able to advise farmers on selective breeding, improving the clam population’s overall resistance to QPX.

“We are generating data that is useful,” Allam said. “Farmers can know what clam strain to breed versus what clam strain to avoid.”

Allam has also used resources from the endowed professorship to connect and collaborate with colleagues across the globe. He recently published a paper with researchers in Italy, using data mining to discover new viruses affecting shellfish, some widespread and others localized to a particular region.

“There’s lots of data sets people generate in their labs and put in repositories of data,” Allam said. “In that data, there is information about viruses that affect these animals, and people don’t look at them, because it’s a small amount of the data. So, we went back, examined that data, and we did the mining of that information and discovered information about several new viruses in that data set.”

Allam’s work perfectly reflects the interests of Laurie Landeau and Robert Maze, an aquatic veterinarian and a PhD in ecological parasitology respectively, whose gift created the Marinetics Endowed Professorship. The endowed professorship continues a long and productive relationship between Landeau, Maze, and Stony Brook that began when Landeau brought the Aquavet program to the University’s Southampton campus.

Since that initial connection, Landeau and Maze have supported SoMAS through the establishment of the Shinnecock Bay Restoration Program, the Maze-Landeau Fellows Program, the Minghua Zhang Early Career Faculty Innovation Fund and the Dean’s Fund for Success. As their relationship with SoMAS and Stony Brook as a whole has grown — Maze chairs the SoMAS Dean’s Council, while Landeau is Vice-Chair of the Stony Brook Foundation Board — their leadership and continued confidence in the School are made even more meaningful by their deep knowledge in the field.

For Stony Brook Interim Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Minghua Zhang, who was dean of SoMAS when the Marinetics Professorship was established, that leadership has made a world of difference.

“For a long time, the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences had no endowed professorship among the tenured and tenure track faculty,” Zhang said. “We were an outlier among schools of similar national and international reputations. It was Laurie and Bob who changed this.”

In formally investing Allam, Landeau and Maze took time to recognize the value of his contributions.

“Bassem Allam is someone we’ve known for a long time and whom we admire greatly,” Landeau said. “What I always hear is how great a mentor he is, and think if any of his graduate students were up here, they’d say the same thing, that he’s not only a great scientist and a leader in terms of the health of the waters around here, but that he’s also a great graduate student mentor.”

“Bassem is a great example of the nurturing, enlightening and rigorous environment that SoMAS perpetuates,” Maze added.

That enthusiasm is shared by Zhang’s successor as Dean of SoMAS, Paul Shepson.

“Prof. Allam brings great credit to Stony Brook University and SoMAS,” Shepson said. “His work on shellfish ecology, physiology, pathology, immunology, and genetics reflect Bassem’s commitment to excellence and to conducting research with great societal value. We are grateful to Drs. Landeau and Maze for their generosity and foresight, and delighted about the recognition that comes with this endowed professorship, and the impact it will have, enabling Bassem to explore and extend his scholarship, and creativity, taking him, we trust, far beyond.”

By the same token, in their continued support of SoMAS, Maze and Landeau exemplify the difference that informed support can make in advancing vital research.

“Support for vital research scholarship is particularly meaningful when it comes from a place of deep knowledge and genuine commitment,” said Stony Brook University Interim President Michael A. Bernstein. “We are grateful for — and honored by — the support that Laurie Landeau and Bob Maze continue to provide to Stony Brook and our School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, including the Marinetics Endowed Professorship.”

As he continues his work as the Marinetics Endowed Professor, Allam is eager to continue making the most of the resources afforded to him by his position.

“I’m looking forward to taking more risk across the board,” Allam said. “Hopefully, this position will enable discoveries where the risk is high, but the return on investment is also high.”

SoMAS Support for Long Beach Water Pollution Control Plant Consolidation Project

Photo Above: A diver prepares to explore the western bays for a study conducted by SoMAS in 2010

The Stony Brook University School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) supports Nassau County and the City of Long Beach’s funding proposals for the implementation of the Long Beach Water Pollution Control Plant (WPCP) Consolidation Project.

The shoreline of the Western Bays region of the South Shore Estuary Reserve is highly developed and modified.

The Western Bays salt marsh ecosystem is an important wildlife habitat, recreational center, and aesthetic asset to Nassau County, but it has a number of significant environmental challenges. Among them are many water quality impacts that threaten public health as well as marine plants and animals. These impacts have been linked primarily to sewage treatment plant (STP) effluent. In fact, the NYS DEC and U.S. EPA considered the Western Bays impaired.

This project will convert the storm-vulnerable Long Beach WPCP into a pumping station with connection to the newly upgraded South Shore Water Reclamation Facility (Bay Park STP). When combined with the Bay Park Conveyance Project, the pump station will transport the treated water from the Bay Park STP to the Cedar Creek WPCP for discharge through an existing pipeline about three miles out in the ocean. This will result in a truly comprehensive and innovative regional wastewater management approach that will service close to one million residents. The outcome will contribute to the overall reduction in treated sewage and thus nitrogen loading into the Western Bays. The project will also create numerous economic opportunities by strengthening tourism and recreation in the region. When completed, these projects will represent a truly significant and lasting investment in bringing the water infrastructure in New York State into the 21st century.

It is largely because of the research undertaken and recommendations made by SoMAS investigators over the last decade that the Consolidation and Bay Park Conveyance Project were developed. Thus, we strongly support this grant application and its focus on improving the health of the estuary and nearshore waters as well as reducing the risk to public health. Further, it will assist in reducing acidification in our estuarine waters, a New York State goal. This coordinated effort between the City and the County will benefit Long Island and the region as a whole.

Thank you for your consideration to grant the necessary funding to implement this project to fruition.

Additional news coverage:

SoMAS Professor Named Interim Provost

SoMAS Professor Named Interim Provost

Dr. Minghua Zhang has been appointed Interim Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs, effective 1 August 2019, Interim President Designate Michael A. Bernstein has announced.

Dr. Zhang has been a member of the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) faculty since 1990 and currently holds the title of SUNY Distinguished Professor. He brings a wealth of administrative experience to this role, having served as Dean of SoMAS from 2010-2016, Associate Dean from 2003-2010, and Director of the Institute for Terrestrial and Planetary Atmospheric Sciences.

“Dr. Zhang is one of our University’s eminent scholars in climate science,” Bernstein said. “He has published in over 140 peer-reviewed articles in top scientific journals, includingScience. Minghua’s research has been supported by over $20 million of cumulative funding from agencies such as the National Science Foundation, the National Administration for Space and Aeronautics, and the U.S. Department of Energy. His accomplishments are some of the most illustrious within the SUNY system.”

Zhang is a Fellow of the American Meteorological Society, an honor bestowed to only the top 1% of its members. He was a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with former Vice President Al Gore.